Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

Qu'y puis-je ?

Il faut bien commencer. Commencer quoi ?

La seule chose au monde qu'il vaille la peine de commencer :

La Fin du monde parbleu.1

- Aimé Césaire (2008, p. 32)

The human species is arguably living through a period of existential challenges unparalleled in history. The planet Earth is undergoing rapid and widespread changes – caused by humanity itself – which have been referred to as an “age of environmental breakdown” (Laybourn-Langton, Rankin and Baxter, 2019), the “Sixth Mass Extinction” (Ceballos et al., 2015) and termed an episode of “biological annihilation” (Ceballos, Ehrlich and Dirzo, 2017). Among other factors, scientists are observing a massive and accelerating extinction of species worldwide: up to 58,000 species are believed to be lost each year (Dirzo et al., 2014), and wildlife populations have plummeted by 69% since 1970 (WWF, 2022). Of one million species that are facing extinction in the coming decades, half of them are insects – which play a critical role in ecosystems and in human food production (Cardoso et al., 2020), particularly pollinating insects, on which an estimated 80% of plants depend for their reproduction (Ollerton, Winfree and Tarrant, 2011). Insect populations have declined by 75% over the past three decades in protected areas of Germany (Hallmann et al., 2017), which has terrible implications for many other areas of the world.

This ecological catastrophe is compounded by global heating, as the planet is on track to reach 1.5°C degrees of warming by 2030 compared to the start of the industrial era (IPCC, 2022a), 2°C degrees Celsius by the early 2040s (Xu, Ramanathan and Victor, 2018), and possibly 6°C to 7°C degrees by the end of the century (CNRS, 2019). Most alarmingly, a recent study published in the journal Science (Armstrong McKay et al., 2022) finds that five dangerous climate tipping points (out of 16 identified) may already have been passed due to global heating, and that at 1.5°C of heating, an additional five tipping points become possible, including the loss of almost all mountain glaciers. These, in turn, may trigger others, and lead to crossing a global tipping point, which would put the planet on a truly catastrophic ‘Hothouse Earth’ trajectory (Steffen et al., 2018). The consequences of this on both the biosphere and humanity are very nearly unimaginable – for example, just 2°C of global warming could expose up to one quarter of the human population to land aridification (Park et al., 2018); researchers consider 4°C degrees of heating as a significant threat to civilisation (Anderson, 2012), and even predict that the carrying capacity of the earth at such temperatures might be no more than a billion human beings (Climate Action Centre, 2011).

Crucially, these catastrophic impacts are already affecting the most vulnerable populations, whose footprint on the earth is the lightest, and will continue doing so (Samson et al., 2011). Of the 2 million people who died from weather, climate and water-related disasters between 1970 and 2019, over 91% of these deaths occurred in countries of the Global South (World Meteorological Organization, 2021). Modelling the impacts of diminishing water quality, coastal hazards, and decreased crop pollination, researchers find that “by 2050, up to 5 billion people may be at risk from diminishing ecosystem services, particularly in Africa and South Asia” (Chaplin-Kramer et al., 2019). According to the IPCC, by the end of this century, extreme heat and humidity could expose 50 to 75% of the global population to “life-threatening climatic conditions” (Chandrasekhar et al., 2022).

Another set of impacts from global heating is the acidification of oceans, as they absorb much of the excess carbon dioxide emitted by human activities. Oceans have grown 26% more acidic since the start of the industrial revolution, which has already had tragic consequences on many marine ecosystems and biodiversity (IGBP, IOC, SCOR, 2013), and by the end of the 21st century, they may have become more acidic than in the past 14 million years (Sosdian et al., 2018). And from the sheer heat of oceanic water alone, over 99% of coral reefs are expected to be lost with a global increase of 2°C (IPCC, 2022b), which would have critical consequences for marine ecosystems and fisheries.

And yet, in spite of increasingly strident calls to action from the scientific community – including an open letter signed by 11,258 scientists from 153 nations, on the 40th anniversary of the first world climate conference (Ripple et al., 2019) – global political efforts aiming at rising to this predicament seem scattered, piecemeal, and orders of magnitude below what would be needed. For example, current pledges and targets made in the wake of the 2015 Paris Agreement would still bring up to 2.5°C of warming by 2100 if they were followed; but current policies are not on track, and we can therefore expect a warming range of at least 2.2°C to 3.4°C by the end of this century (Climate Action Tracker, 2022). In fact, 4°C increases are in the “very likely” range within the IPCC’s most recent Working Group I report (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021), and its worst-case scenario for greenhouse gas emissions remains the best match for cumulative emissions between 2005 and 2020 (Schwalm, Glendon and Duffy, 2020).

One possible set of reasons for the lack of meaningful climate action is the extreme inequality in people’s access to wealth and political agency in the world. In 2017, eight men owned the same wealth as the poorest half of the world (Oxfam, 2017) – and between 2020 and 2023, 1% of the global population captured two-thirds of all wealth created in the world (Elliott, 2023). The average investments from one of these billionaires, alone, emit more than a million times more carbon than the average person (Dabi et al., 2022). At the level of nation-states, research has shown that historically, the G8 nations (the USA, EU-28, Russia, Japan, and Canada) were together responsible for 85% of excess global CO2 emissions (Hickel, 2020), as a direct result of colonialism and plunder (Abimbola et al., 2021). Today, high-income countries continue to drain resources from the Global South, and to enrich themselves through “imperial forms of appropriation to sustain their high levels of income and consumption” (Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala, 2021, p. 1). In other words, the people who are most exposed to the immediate consequences of the ecological crisis continue to be exploited by those least exposed. This is compounded by failing national and global governance processes, which do little to keep in check offshore tax evasion and limit wealth accumulation (Garside, 2017; Eisinger, Ernsthausen and Kiel, 2021), or to prevent entanglements between public and private sector allowing corporations to bring about legislation more effectively than a country’s inhabitants (Crouch, 2004).

It is becoming painfully evident that the modern industrial civilisation, which requires economic growth to sustain itself as a result of the debt-based monetary system at its core (Arnsperger, Bendell and Slater, 2021), is unjust and unsustainable. And yet, dominant policy responses to this dire state of affairs continue to be about maintaining current structures in spite of the magnitude of the challenges. For example, the “green growth” theory asserts that “continued economic expansion is compatible with our planet’s ecology, as technological change and substitution will allow us to absolutely decouple GDP growth from resource use and carbon emissions,” even though empirical research shows that this is likely not achievable (Hickel and Kallis, 2019, p. 1). As for “Green New Deals” – policies advocating for a system-wide transition away from fossil fuels and a massive expansion of renewable power resources, in response to the climate crisis – they would require a huge increase in the extraction of key minerals, such as lithium, graphite, nickel, and rare-earth metals. This increase in demand appears both impossible to meet for the whole world in a short enough time frame to respond to deadly global heating (IEA, 2021), and the social and ecological impacts of delivering that level of supply would be enormous, particularly for Indigenous and marginalised peoples and the ecosystems they steward (Zografos and Robbins, 2020). Indigenous peoples play a critical role in conserving around 21 percent of all land on Earth, far more than states do through national parks (ICCA Consortium, 2021), and are already over-represented among human rights defenders killed around the world (Front Line Defenders, 2021).

Ripple and colleagues, in their “World’s Scientists Warning of a Climate Emergency” (2022), warn of being at “code red” on planet Earth, and of the “rapidly growing” scale of “untold human suffering” caused by the “major climate crisis and global catastrophe.” Other scientists point to the necessity of exploring much more thoroughly the possibility of “cascading global climate failure” due to climate inaction (Kemp et al., 2022), as well as “plausible” scenarios of global or localised societal collapse (Steel, DesRoches and Mintz-Woo, 2022). Even the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, in a report endorsed by UN Secretary-General Guterres himself, evokes the increasing probability of global civilisational collapse, as a result of escalating synergies between disasters, economic vulnerabilities and ecosystem failures (UNDRR, 2022). A “catastrophic collapse in human population” seems more than likely to occur if resource consumption and widespread deforestation continue unchecked (Bologna and Aquino, 2020, p. 8). In fact, for some scientists, the damage visited on the entire biosphere may even compromise the long-term survival of the human species (Kareiva and Carranza, 2018)...

From the above, I cannot but agree that “we are in the accelerating phase of the Great Unravelling of the web of life” (Kelly and Macy, 2021, p. 199), and that a global societal collapse appears to be the most likely outcome of climate change and ecological disruptions if current trends continue (Servigne and Stevens, 2020).

There is something obscene about going through this (by no means comprehensive) list of scientific references about the unfolding calamities of the world in the purest academic style. As I write these lines, I simultaneously experience the cold satisfaction that comes to me from oh-so-patiently and systematically piecing information together with my reference management software, which creates a reassuring distance between myself and what I am writing about; as well as the deep horror, disgust, anger and grief evoked by these “data points,” materialising as a painful knot in my stomach, tears at the corners of my eyes, and an urge to scream out at the top of my lungs. And I wonder, for the umpteenth time since I embarked on this PhD research: “What’s the point of all this? Don’t I have better things to do than write a thesis in this time of collapse, this time of great dying?!”

I also realise that my younger self, the me from when I received my previous degree about 14 years ago, would have been quite incredulous and perhaps even appalled to learn that I would eventually decide to go back to a “manipulative institution” like the schooling system (Illich, 2003). How did I come to make this choice?

I expect the reader may benefit from more information as to how this thesis came to be written. So I will sketch a brief outline of the journey that led me here.

On November 9th, 2016, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. By some strange coincidence, this also happened to be the day of my thirty-first birthday. I felt like the universe had delivered me a very mysterious gift. Alone, sleepless and depressed in an old hotel room in Fukuoka, Japan, I contemplated the sorry state of the world. It dawned on me that I could no longer keep on looking the other way.

I obtained my Masters degree in sustainable policymaking in 2009, and worked for some years at a small French consulting firm. But eventually I started doubting the usefulness of our activities, and of sustainability consulting as a whole, and left the company. For a few years, I organised concerts and film screenings at an independent art centre in Beijing which I co-founded with a few friends, and made a living as a freelance translator. This now seemed very self-indulgent. Global heating was continuing unchecked – the limitations of the so-called “historic” Paris Agreement were plain to see – and a climate change denier was now in control of the world’s military superpower and its climate-destructive economy. Species were being decimated at an unprecedented rate. The Dark Mountain Manifesto (Kingsnorth and Hine, 2009) haunted me. It did seem that we were “in a time of social, economic, and ecological unravelling.” How could translating obscure academic prose be helpful to anyone? What could I do that might be more relevant?2

I decided to set off on a journey of discovery, and to find what role I might play in the vast mess we were in. Over the following months, I lived a quasi-monastic life, holed up in a tiny room and reading as much as I could on various aspects of the global social and ecological predicament. Occasionally, I wrote lengthy blog posts summarising my insights, which I doubt anyone except close family members ever read.

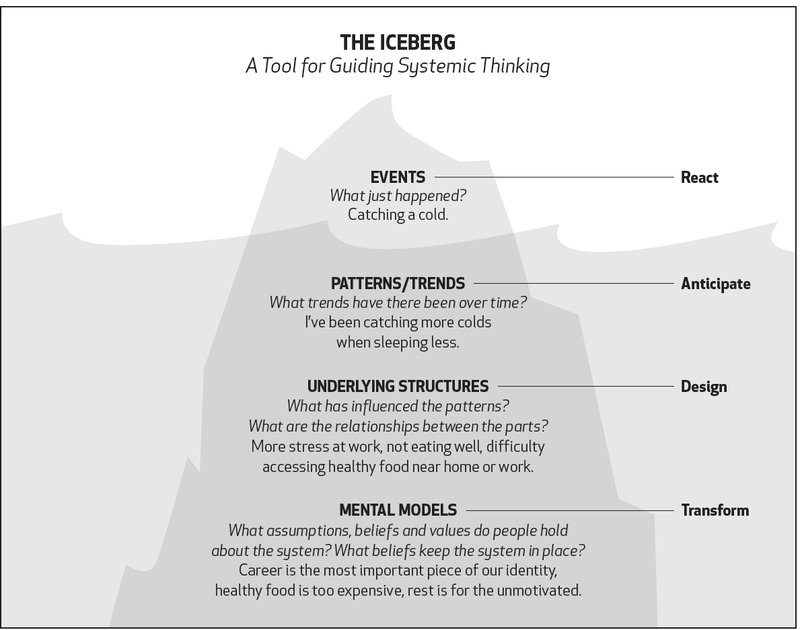

As I explain in one of these texts (Cavé, 2017), in my search for the most meaningful role I could take on, I drew inspiration from systems thinking, and in particular from the “iceberg model” (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Iceberg Model (Ecochallenge.org, no date)

The model felt like a useful tool to reflect on the global social and ecological crises I was witnessing. It pointed to destructive mindsets as the root cause of these crises – and thus, as the most powerful locus of change. I found confirmation of this in the writings of Donella Meadows (1999), who spoke of paradigm changes as the most potent leverage points for social change.

Zen poet Thich Nhat Hanh was asked, “What do we most need to do to save our world?” His questioners expected him to identify the best strategies to pursue in social and environmental action, but Thich Nhat Hanh’s answer was this: “What we most need to do is to hear within us the sounds of the Earth crying.” (Macy, 2007, p. 95)

How to transform these harmful mindsets which, embedded in the culture of industrial civilisation, were driving the human and other-than-human world to the abyss? How to enact the spiritual and cultural transformation called for by Thích Nhất Hạnh?

This seemed to be a matter of education. I had heard of “education for sustainability” curricula being introduced in certain schools, which could have been a promising track. However, I felt a deep distrust towards mainstream educational systems. This was a result of my own experience with the French schooling system, which I had keenly felt was explicitly valuing certain forms of knowledge and skills – especially those related to the “hard sciences” – over arts or the humanities, as well as certain forms of intelligence – especially the capacity for logic and rationality – over others. I also remembered how the courses I had followed, during my sustainability policymaking degree, had mostly been promoting rather tame and business-as-usual approaches to “sustainability issues,” instead of encouraging the more imaginative and radical explorations that I now felt the global predicament truly required.

Reading Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society (1971) gave substance to my dissatisfaction. He showed, convincingly in my view, how schools reproduced social inequalities and the consumerist mindset; how they were an instrument of social control; and how the obligatory schooling system had established a unjust monopoly, within industrial society, as the institution specialised in education, at the expense of any other contexts (such as workplaces) in which people had been learning the most essential things in life since time immemorial. Illich called for a disestablishment of this monopoly that “legally combines prejudice with discrimination” (p.11), and for a recognition that “most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting” (p.39). He argued that “a radical alternative to a schooled society requires not only new formal mechanisms for the formal acquisition of skills and their educational use. A deschooled society implies a new approach to incidental or informal education” (p.22 – my emphasis).

This felt intriguing and exciting. What might such a new approach to informal education look like? Could it help change hearts and minds in a relevant way, in view of the gravity of the global predicament?

One idea of Illich’s, in particular, appeared both prescient and fascinating to me. In this same book, he advocated for the development of “educational webs” as means to support self-directed education through intentional social relations, “for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring” (p.xix-xx). In a rather visionary way, Illich even foresaw the potential of computers in creating decentralized “peer-matching networks” (p.93) to enhance autonomous forms of learning in society.

Finally, as I was pondering these questions, a new wave of social movements was exploding onto the public scene in response to climate inaction – most prominently Extinction Rebellion, and the School Strike for Climate movements. I saw that the non-violent, direct actions of Extinction Rebellion (XR), which aims at applying pressure on governments worldwide to take action on the climate and ecological crisis, were supported by dozens of academics and public personalities, and thousands of ordinary people willing to risk arrest (Taylor and Gayle, 2018; The Guardian, 2018). And I was impressed with how XR activists in the UK cleverly used online tools to coordinate their actions in the UK, but also to liaise with local activists in dozens of countries (Taylor, 2019), and thereby secured much media attention (Townsend, 2019). Largely in response to the actions of such movements, the UK Parliament declared a “climate emergency” in May 2019 (Turney, 2019), soon followed by over a thousand local and national governments (Climate Emergency, 2020).

XR actions were shown to have raised environmental consciousness in the UK to an “all-time high” (Smith, 2019). And I wondered: How are these social movement networks enabling the activists, themselves, to learn and change as they are taking part in these movements? Could these networks of action become something akin to the convivial “educational webs” that Illich had written about?

One day, I heard about the opportunity to enrol in a PhD programme at the Initiative for Leadership and Sustainability, University of Cumbria. I felt a great reluctance to step back into the neoliberal academic system, which seemed to hold very little potential for the deep social change that was so urgently needed. However, I was also conscious that this programme might help me adopt a more structured approach to my investigation, instead of staying buried in my books. And because the University was supportive of professional learning and action research, I would be able to study an area that I was practising in, as I was getting involved professionally in online networks. Finally, I came across a modest inheritance that allowed me to pay the tuition fees! So after much soul-searching, I decided that this was a sign from the universe, and enrolled in the programme.

Since then, the research question I set upon exploring has been the following: “How may online networks enable radical collective change through social learning?”

In the remainder of this introduction, I will say more about the perspective from which I undertook this investigation. But first, I need to say more about the dark side of technology.

People with whom I discussed this research were often surprised to learn that I was not at all active on any major social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube. But while I have long been curious about the potential for socio-technical networks to enable radical forms of collective change, I am also extremely suspicious about these technologies. I certainly don’t think they are necessarily a force for generative change. In fact, there appears to be much more evidence to the contrary.

First of all, the physical impact of information and communication technologies (ICT) on the biosphere and on human beings is vast, and increasing. In 2019, the use of ICT alone caused around 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and their energy footprint is increasing by around 9% per year (The Shift Project, 2019). By 2025, the IT industry could use 20% of all electricity produced in the world, and emit up to 5.5% of global carbon emissions (Jones, 2018). And while Big Tech giants attempt to present themselves as environmentally conscious, they are not at all committed to reducing emissions originating from their value-chain (Day et al., 2022), and generally only act to reduce a tiny part of their carbon footprint (Diab, 2022). Besides, increasingly sophisticated digital technologies require the use of metals with very specific properties, which are becoming increasingly rare and whose extraction is a cause of environmental disasters (Tréguer and Trouvé, 2017; Katwala, 2018) and egregious labour exploitation, often involving children (Lee, 2022; U.S. Department of Labor, no date). In 2019, only 17.4% of all e-waste in the world was actually collected and recycled, and it is estimated that the sheer mass of new e-waste generated per year will have doubled by 2030 compared to 2014 (Forti, 2020). The toxic substances contained in this waste are very harmful to habitats, people, and wildlife, and also contribute directly to global heating (ibid). Finally, like minerals extraction, both the assembly and the recycling of ICT involve ruthless exploitation of labour (Condliffe, 2018; Albergotti, 2019; KnowTheChain, 2020; WHO, 2021).

Besides, mainstream social media platforms, and the devices that enable them, also bring about many harmful social and political impacts, which seem to hinder social learning and generative change in the face of the global predicament.

Digital platforms and their revenue-maximising algorithms have been decried for impacting public discourse through increased political polarisation (Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2021). One of the key ways social media recommendation algorithms have found to keep users “hooked” has been to deliver increasingly edgier versions of whatever the user was reading or watching, regardless of the credibility of the content source, which has favoured the spread of conspiracy theories (Tufekci, 2018). A side-effect of this proliferation of narratives has been increased mistrust and doubt (Tufekci, 2018; Sacasas, 2020a), which arguably weakens the capacity for collective sense-making and action, to the advantage of established power structures (King, Janulewicz and Arcostanzo, 2022). Furthermore, this ceaseless consumption of digital content appears to prevent many individuals from nurturing meaningful connections with the world beyond their screens, and thus from truly experiencing the gravity of the global social and ecological catastrophe that is unfolding – likely an obstacle to any forms of radical collective change taking place (Hétier and Wallenhorst, 2022).

According to the philosopher of technology L. M. Sacasas (2020b, 2022a), the internet has generated a “superabundance of information” which has contributed to widespread epistemic fragmentation. He suggests that digital media have brought an end to the “age of consensus” created by print and mass media, and introduced “digitized realms incapable by their nature and design of generating a broadly shared experience of reality.” Similarly, Zygmunt Bauman (2011) points to an “information deluge” (p.7) as a key characteristic of “liquid modernity,” which leads people to seek to protect themselves from the overwhelming level of noise, thus leading to a fractured common sense. As a result, for Sharon Stein (2021), “many people are increasingly encased within their own personalised knowledge bubbles… whether or not one agrees that consensus is a desirable goal, today it appears to be an increasingly impossible one” (p.484). This is surely another issue with regards to the possibility of collectively addressing our global social and ecological predicament.

Not only do social media hamper meaningful dialogue from taking place between groups with different visions of reality – they appear to encourage animosity and group loyalty manifesting as sectarianism. Indeed, social media platforms amplify ongoing “culture wars,” as every user is primed to always want to be seen as playing for the right “team” – or at least, will fear being perceived as playing for the wrong one (Haidt, 2022; Sacasas, 2022b). This favours the expression of hate speech and toxic communication (Brady et al., 2017; Munn, 2020; Rathje, Van Bavel and van der Linden, 2021), which is certainly not conducive to mutual learning.

Finally, although the internet and online social networks have been hailed as tools enhancing people’s ability to take part in collective action within social movements (Castells, 2000, 2012; Shirky, 2008), their actual role in creating political change is very uncertain. Studies have found that social media may be “less useful as a mobilizing tool than a marketing tool” (Lewis, Gray and Meierhenrich, 2014). More worrying, research has shown that these tools are also extremely effective in the hands of authoritarian regimes, who can use them to suppress free speech, hone their surveillance techniques, and disseminate propaganda (Morozov, 2012; Tufekci, 2018). Indeed, the spread of digital devices into every space of people’s daily lives has been accompanied with a corresponding increase in big data collection, storage, and analysis, on behalf of private companies as well as public bureaucracies, which establish partnerships for purposes of surveillance and communications censorship, without barely any democratic oversight (Zuboff, 2019). We now live in an age of “digital authoritarianism” (Fisher, 2022), in which governments are successfully preventing social movements from achieving a critical mass of support by sowing doubt, division, or detached cynicism within their ranks. Perhaps as a result, the usefulness of protest appears to have decreased as a means of political change (Chenoweth, 2017).

In summary, these tools appear to play an instrumental role as part of the social, political and ecological woes of our time. Far from paving the way to a more sustainable, caring, and democratic society, they are destructive, exploitative, addictive, and divisive, as well as primary means of control and repression. Considering the above, I was not surprised to face incredulity in many people, upon mentioning my interest in the emancipatory potential of online networks: “Do you really believe that these technologies can make the world a better place?” And yet, had I not been trusting in the existence of this potential, I would not have undertaken this PhD research. What kept me going?

A simple answer is that I consider it a grave mistake to reduce the internet – and ICT as a whole – to the socially and ecologically harmful tools provided by the mega-corporations referred to above. Indeed, thousands of “hacktivists” worldwide have long been developing and promoting free and open-source software that offers powerful alternatives to mainstream social media, and which are often oriented towards radical collective change. For instance, decentralised social media gathered in the "Fediverse," such as Mastodon, do not turn their users into objects of surveillance and value extraction (Rozenshtein, 2022). One of these platforms, Mobilizon, is an “emancipatory tool” that provides an “ethical alternative to Facebook events, groups and pages,” allowing people to “gather, organise and mobilise” for social change (Framasoft, no date).

Such platforms bring together fewer users, largely due to the difficulty of competing against the financial capabilities of commercial platforms, which can afford to hire thousands of designers to make their products more attractive and addictive. Yet these alternatives do exist. And in spite of the dominance of exploitative Big Tech, and the alliances they forge with repressive state actors, I trust that “hacktivists” will always find ways of using means of online communications to federate the energy and intentions of rebellious minds and hearts around the world.

For better or worse, digital devices and platforms have become part of our everyday lives. I believe that it is possible for humans to build meaningful relationships using these tools, to turn them into the conduits for mutual learning that Ivan Illich envisioned, and to wield them as a force for generative social change – although this certainly requires us to relinquish naivety, to keep honing our tech literacy and critical discernment, and to fully acknowledge and address the many harmful aspects that are embodied in the very material infrastructure of the internet. The aim of my research has been to investigate this possibility.

I view myself as an activist-scholar in training. As such, I want to try and pay close attention to the historical geometries of power involved in the production of knowledge when academics such as myself engage with the outside world, and to my “location in an elite, dominant institution that is enrolled in the process of reproducing a particular social order” – i.e. the university (Duncan et al., 2021, p. 880). This has led me to embrace a participatory methodology (see Chapter 3), and to carry out an ongoing critical reflection on my own practice, assumptions and beliefs (Chapter 3, Chapter 6).

I embarked on this research project with the intention to generate practical knowledge with regards to generating radical forms of collective change in the context of online networks and the communities they support. My wish is that the content of this thesis, and the other outcomes of this research, may be of practical use to anyone wishing to address the fundamental issues of our time.

For this reason, this study can be viewed as an attempt at producing “movement-relevant theory” – or scholarship which prioritises the relevance of research to social movements themselves, following the definition offered by Bevington and Dixon (2005). As a researcher, I do not pretend to know more than activists deeply involved in their practice and learning from it, nor do I pretend to be better able to generate theory. However, I hope to aid and celebrate the ongoing learning taking place in prefigurative groups and social movements, by contributing my time and access to potentially useful scholarly literature, and helping to produce scholarship that can be of use to those seeking social change. This does not imply an uncritical stance with regards to the assumptions or practice of these groups, however: “it is in the interests of that movement to get the best available information, even if those findings don’t fit expectations” (Bevington & Dixon, 2005, p.191). I seek to adopt the stance of the “radical intellectual” theorised by David Graeber (2004):

to look at those who are creating viable alternatives, try to figure out what might be the larger implications of what they are (already) doing, and then offer those ideas back, not as prescriptions, but as contributions, possibilities—as gifts. (p.12)

Furthermore, throughout this project, I have also become increasingly conscious of the need to remain aware of the need for me, as a researcher, to “build radical, intersectional, and transformative research practices against the exploitative and extractive traditions of academe” (Luchies, 2015, p. 523) and therefore to “actively [take] part in naming and dismantling oppression and exploitation” (ibid, p.524) – including imperialism, heterosexism, ableism, capitalism, and cis-/male and white supremacy.

I also want to acknowledge the non-linear, mycelial nature of this research project.

Considering the immensity of the global predicament, and the complexity of addressing it in meaningful ways, I did not wish to remain wedded to any particular theory, but sought an open-ended, emergent and flexible approach that would allow me to carry out social learning experiments, and to keep reflecting on their outcomes. This led me to use Action Research (Chapter 3), and to rely on structuring metaphors (Chapter 5, Chapter 6) to account for my evolving perspective.

As a result, my inquiry has led me to investigate a variety of fields of knowledge and methodologies, to go down multiple research tracks, and to bring together conflicting and diverse perspectives. Like a fungus, this participatory project has fed on a variety of more or less nutritive substances, and formed an anarchic whole that may appear rather “messy” and difficult to delineate. Witness, the many annexes I am appending to the main body of this thesis.

What I have found, like other action researchers before me (e.g. Cook, 2009) is that “messiness” may better enable inquirers to engage with multiple forms of knowing – as I do in Chapter 6. In their extended epistemology, John Heron and Peter Reason theorise four different forms of knowledges, including: experiential (knowing through empathy and attunement with present experience); presentational (a form of knowledge construction expressed in graphic, plastic, moving, musical, and verbal art forms); propositional (knowing expressed in the form of formal language); and practical knowledge (the ability to change things through action) (Heron, 1996; Heron and Reason, 2008). While this thesis largely foregrounds propositional knowing, I believe it also contains nuggets of each other form of knowledge from this list. It is my hope that together, these “kaleidoscopic views” and “multi-faced reflections on practice” may “provide opportunities for new ways of seeing, thinking and theorising” (Cook, 2009, p.280) – and thereby offer a variety of paths for the study and enactment of collective change. Indeed, embracing a “messy turn”

can be professionally and personally uncomfortable but vital to research that seeks to engage in contesting knowledge leading to changes in practice. (ibid, p.285)

Journeys are not the tame servants that bear you from one point to another. Journeys are how things become different. How things, like wispy trails of fairy dust, touch themselves in ecstatic delight and explode into unsayable colors. Every mooring spot, every banal point, is a thought experiment, replete with monsters and tricksters and halos and sphinxes and riddles and puzzles and strange dalliances. Every truth is a dare. To travel is therefore not merely to move through space and time, it is to be reconfigured, it is to bend space-time, it is to revoke the past and remember the future. It is to be changed. No one arrives intact. (Akomolafe, 2017, p. 250)

As with any true journey, my point of arrival is quite different from my point of departure – and I have been changed and reconfigured by this investigation. I started off looking for ways in which online networks and communities may enable their participants to learn more about important social issues, and to take action to address them. I explored this question using diagnostic processes and social learning evaluation.

However, the reader will notice a shift toward a more critical perspective at the end of Chapter 5 and into Chapter 6.This instance of “messiness” reflects my own journey of learning and change. Through my engagement with decolonial discussion spaces and literature, I came to the conclusion that generative social change is not just a matter of learning how to organise better, but also (and more importantly) about gaining awareness of the toxic cultural patterns of being, knowing, and doing that have brought about the global predicament, and how these are unconsciously reproduced by anyone within modern-colonial societies, including by activists in social movements. From this perspective, it is important to consider one’s own implication in these less generative patterns in order to try and “compost” them through a process of unlearning, for radical forms of change to emerge. By “radical collective change,” I refer here to forms of collective change that would constitute a relevant response to contemporary socio-ecological crises. I will explore this notion more deeply in Chapter 6.

This led me to pay more attention to my own positionality within the context of the online communities introduced here, and in my knowledge production. For instance, I come from a White, Western, middle-class background; I can fluently express myself in English, and in other globally dominant languages; and I am heterosexual, male, able-bodied, and a PhD researcher, which are all dimensions that grant me power and privilege. And as most participants in the online communities described in my case studies (Chapter 4 and 5), too, were from the Global North, these chapters will likely be most useful to readers hailing from backgrounds of similar privilege – and who could be viewed as involved in “low-intensity struggles” (GTDF, 2020)3. Overall, I view my own journey of (un)learning as offering food for thought to researchers who find themselves on a path akin to mine as I began my investigation, and who may want to bring more reflexivity to their approach.

In the following chapters, I situate this thesis within relevant fields of study, with a particular focus on those of informal and social learning, online communities, prefiguration, and decolonial studies (Chapter 2). Then, I introduce the methodology that I followed, and which was centred on the use of first- and second-person Action Research, and on two forms of participatory social learning evaluation (Chapter 3). The next two chapters present the results of two case studies, each carried out within a particular online community: FairCoop (Chapter 4), and the Deep Adaptation Forum (Chapter 5). Reflecting on these results, and on other aspects of my personal journey of (un)learning, allows me to refine my own notion of “generative radical collective change,” and to suggest conditions that may allow this to happen within the context of prefigurative online communities (Chapter 6). In conclusion, I summarise the answers I have found to my research question, and consider areas for future research (Conclusion).

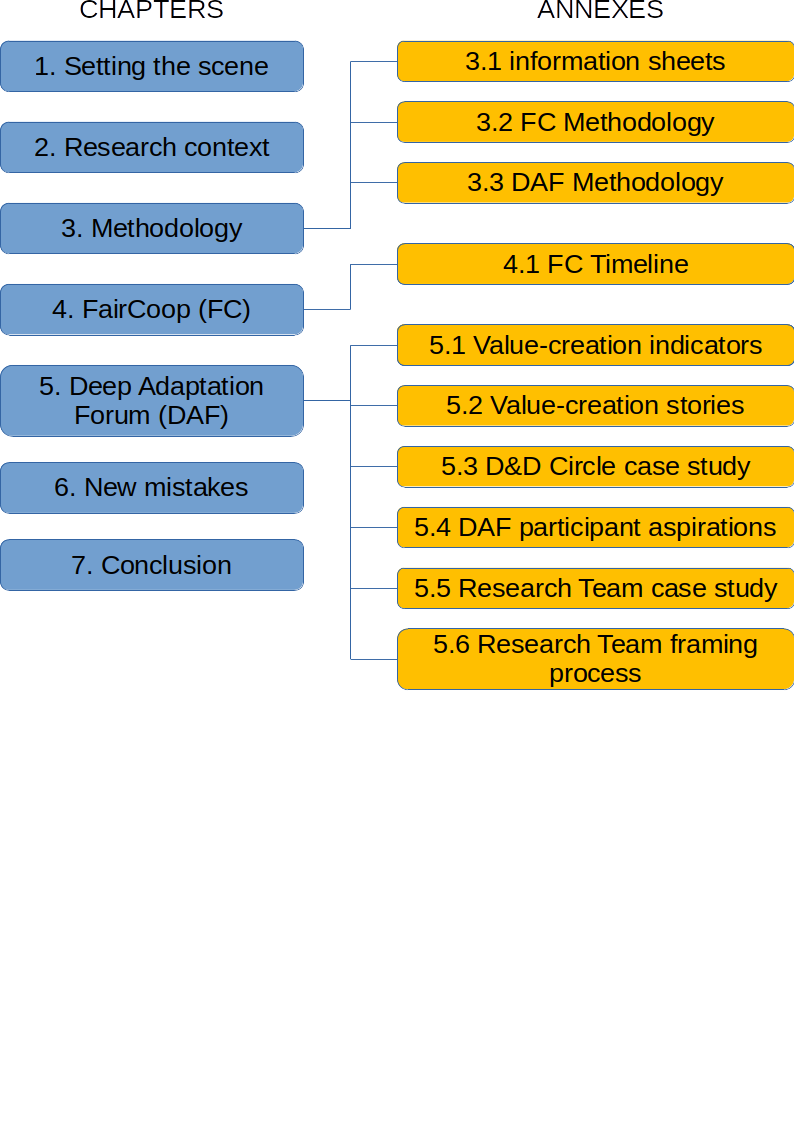

Additional information for Chapters 3, 4, and 5 is provided in annexes. Here is a list of these annexes, along with a brief description of each. Please see Figure 2 for a simplified “road map” of these chapters and annexes.

Chapter 3:

- Annex 3.1 presents the online information sheets I have used to introduce this research project in FairCoop (FC) and the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF).

- Annex 3.2 gives more details about the methodology followed for the case study presented in Chapter 4 (on FC).

- Annex 3.3 gives more details about the methodology followed for the case study presented in Chapter 5 (on DAF).

Chapter 4:

- Annex 4.1 is a timeline of the development of FC.

Chapter 5:

- Annex 5.1 shows the value-creation indicators compiled for the social learning evaluation in DAF.

- Annex 5.2 shows the list of value-creation stories compiled as part of this same evaluation.

- Annex 5.3 presents a detailed evaluation of social learning processes within the DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle (D&D).

- Annex 5.4 is a discussion of the main aspirations voiced by DAF participants with regards to their involvement in the network.

- Annex 5.5 presents a detailed evaluation of social learning processes that occurred within the DAF Research Team, and as a result of its activities.

- Annex 5.6 shows the research framing process that was carried out by the DAF Research Team as part of its self-evaluation.

Figure 2: Thesis chapters and annexes