Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

Annex 3.3

Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

In this annex, I provide more details about the Wenger-Trayner theory of value-creation in social learning spaces (outlined in Chapter 3), and about the corresponding evaluation methodology. I then explain how I have used this methodology as part of my research processes in the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF).

1. Value-creation theory

As mentioned in Chapter 3, social learning spaces create value for participants to the extent that the latter view engaging uncertainty and paying attention as contributing to their ability to make a difference they care to make (and this value can be positive, negative, or null).

1.1 Social learning modes

There are four main social learning modes that are “inherent in all social learning spaces, whether or not they are perceived, articulated, or facilitated as such” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.62-3):

- social learning spaces generate value to the extent that they “produc[e] something of value toward making a difference” for their participants;

- when participants “tak[e] something of value and do something with it” (for example, if they try out in practice a new idea heard from someone), they are translating value;

- framing is what happens whenever participants engage in activities that shape their own aspirations and expectations for value creation within a particular space, as they discover and decide what difference(s) they care to make; and

- evaluating is about “inspecting the difference learning is making or not” – be it informally, by paying attention to any new changes, or by undertaking specific data collection and analysis processes.

These learning modes are not sequential, but rather in a state of constant interplay. Together, they “constitute social learning” while “offer[ing] distinct channels for agency” (ibid, p.64).

In this study, I have focused in particular on the evaluation mode, as I have initiated processes aiming at examining the social learning taking place in DAF, and its relevance to radical collective change.

What are the different kinds of value generation that can be assessed through the Wenger-Trayner framework?

1.2 Value-Creation Cycles

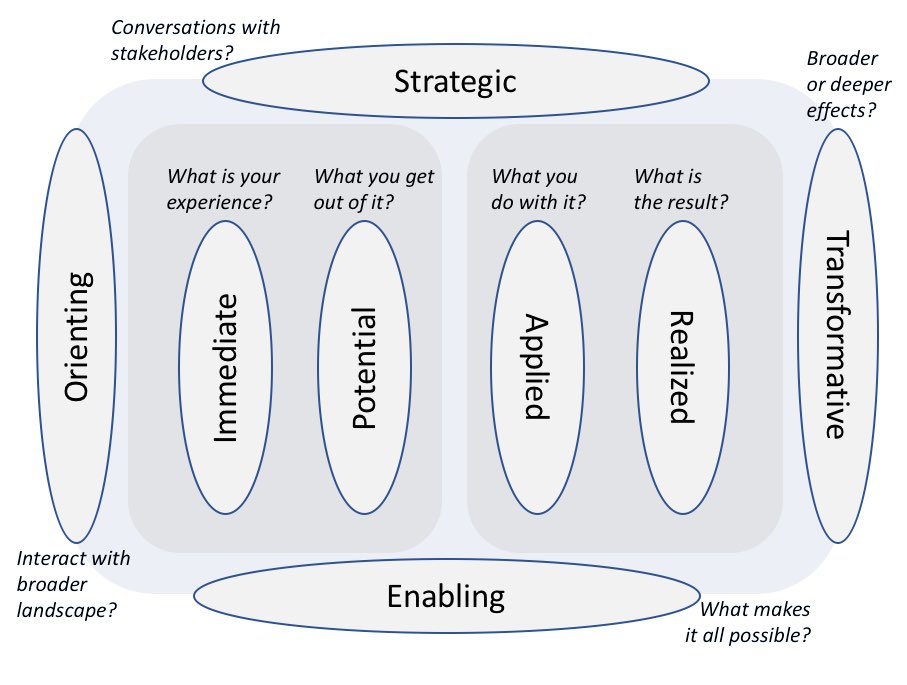

In a social learning space, value can be created within and across eight different value-creation cycles (Figure 14). Each of these cycles corresponds to an intricate process of value being created “progressively and iteratively over time” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.75). Value created in one cycle can flow (by being translated) into another cycle, but this does not happen in a linear or predictable fashion, and there is no overarching definition of success for these social learning processes. The framework allows for a fine-grained and flexible evaluation of how these processes unfold for a person or a group.

Figure 14: Value-creation cycles (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020)

Each cycle can be described using a guiding question, and illustrated through certain main dimensions of value-creation (ibid, p.79-122). I provide an overview of these in Table 3.

Table 3: Value-creation cycles with their main guiding questions and some illustrative dimensions

Value-creation cycle |

Guiding question |

Illustrative dimensions of value-creation |

Immediate |

What is the experience like? |

Identification Sense of inclusion Mutual recognition as learning partners Conviviality and enjoyment Productive discomfort Contestability Engaging with other perspectives etc. |

Potential |

What comes out of it? |

Concrete help with specific challenges Innovation Stories of others’ experiences Insight Critique Skills Information Resources Self-worth Social capital etc. |

Applied |

What are we learning in the doing? |

Inventiveness (as a source of innovation in practice) Adoption/adaptation Reuse Increasing one’s influence Resisting more effectively Harnessing synergy Leveraging connections better etc. |

Realised |

What difference does it make? |

Personal difference (better performance and achievements for participants) Collective difference (for participants as a group) Difference for stakeholders Difference for the organisation Societal difference (contributing to a public good) etc. |

Enabling |

What makes it all possible? |

Commitment Internal leadership Transparency Process Social learning support Logistics and technology Strategic facilitation etc. |

Strategic |

What is the quality of engagement with strategic stakeholders? |

Various constituencies Strategic context Aspirations and expectations Ongoing engagement Power Alliances etc. |

Orienting |

Where do we locate ourselves in the broader landscape? |

Participant contexts Biographies and identities Personal networks History and culture Power structures External audiences etc. |

Transformative |

Does the difference we make have broader effects? |

Personal transformation Power shifts New identities Institutional changes Empowerment etc. |

Again, it is important to remember that value created in a social learning space is not always positive, but can actually be negative, or null. So the dimensions highlighted above can be useful to pay attention to unhelpful, non-generative value being created, or to the absence of value-creation in a particular cycle.

For more discussion of each of these cycles and concrete illustrations of the type of value-creation that they cover, please refer to the case studies in Annexes 5.3 and 5.5.

1.3 Social learning evaluation

How to assess the creation of value across the different cycles in a social learning space, while honouring the agency of participants?

Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2020, p.189) have developed an evaluation framework that I find particularly suited to an Action Research approach, in that it is:

- Flexible – it “allows for various degrees of formality”;

- Participatory – it “accommodate[s] different perspectives with participants helping define the parameters”; and

- Dynamic – it “account[s] for the evolving nature of social learning with its inherent unpredictability.”

This framework allows for any participants in a social learning space to carry out their own social learning evaluation, as “value detectives” (ibid, p.228). Its main purpose is twofold:

- to ascertain whether value has been created in the lives of participants of a social learning space, at a given cycle;

- and to check to what extent the space contributed to this effect.

For this purpose, the value detectives need to collect:

- Effect data, establishing that some difference was made in a given cycle. This data can be quantitative or qualitative, and based on participants' testimonials or other sources (e.g. web analytics, statistics, etc.). This data is used to define indicators that are meaningful to participants, and which can corroborate value-creation stories.

- Contribution data, establishing the role of the social learning space in creating that difference. This data takes the shape of value-creation stories, which are testimonials from participants that account for the flow of value (social learning) across various learning cycles. In other words, these stories establish the role of the social learning space in making the difference that is valued by participants in the space.

To form a robust picture of value creation, these two types of data should be collected iteratively, and in an integrated way, with cross-references between the two:

Each cycle is a potential integration point because stories can mention effects at any cycle and data can be collected about such effects. The idea is to monitor indicators (quantitative and/or qualitative) for as many cycles as possible and collect value-creation stories (qualitative data) referencing as many monitored indicators as possible. The integration between the two can be dynamic. Effect data calls for stories to explain how effects came about while stories point to effects that may need to be monitored. (ibid, p.192)

Contrary to most evaluation methods used in project management or development studies, this framework does not aim to assess whether a project or programme has met objectives and targets established by donors or a management team, but whether a social learning space is enabling its members to make the difference that they are trying to make – individually and collectively – through their participation in that space. This framework is designed to be flexible and value-agnostic: it doesn’t impose a normative set of indicators as criteria for what constitutes “valuable learning” - but considers that “what counts as success – or value – is under ongoing negotiation among stakeholders; it is changing as circumstances and people evolve […].” (p.189). And finally, it is also meant to function as a feedback process, helping to “deepen the learning” taking place in the space (p.193).

Therefore, this framework appears particularly useful to a participatory Action Research project like the one I undertook.

Having presented the main components of the Wenger-Trayner social learning theory and evaluation framework, I will now explain how I have used them within DAF.

2 Evaluation processes in DAF

2.1 First research cycle

This action research project in DAF began in January 2020. Members of the DAF Core Team, including myself, collaborated with DAF volunteers to create a survey that would be disseminated across the network: the DAF 2020 User Survey. This survey had the twin objective of assessing the usefulness of DAF platforms, and the learning and changes taking place for participants thanks to these platforms.

The survey was open from January 2 to February 25, 2020. A preliminary summary of results was shared in DAF on February 29, 2020. Partial results were also shared on the blog of the Initiative for Leadership and Sustainability, on June 8, 2020 (Bendell and Cavé, 2020). Later, I produced a report providing a more in-depth analysis of the survey results (Cavé, 2022b).

There were 168 survey respondents. In early April 2020, using simple random sampling, I selected 10 of those who had indicated in their response that they would be willing to be contacted by a member of the research team. I reached out to each of them to arrange for a one-hour interview.

With these interviews, I had two main objectives:

- To start gathering contextual narratives – i.e. relatively unstructured accounts that are aimed at “broadly capturing the perspective of the narrator on the history and value of a social learning space” in order for participants’ perspectives to “reveal avenues for inquiry” and “point out where value is created and where some credit should be given for contributing to this value” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.230-231). This can be particularly useful in order to begin mapping out indicators of value-creation to monitor (and thus, the creation of effect data); and

- To begin collecting value-creation stories (as contribution data).

Due to the focus of the survey on the usefulness of DAF platforms, I was particularly interested in investigating what aspects of DAF platforms seemed to play an enabling or disabling role with regards to social learning for these participants.

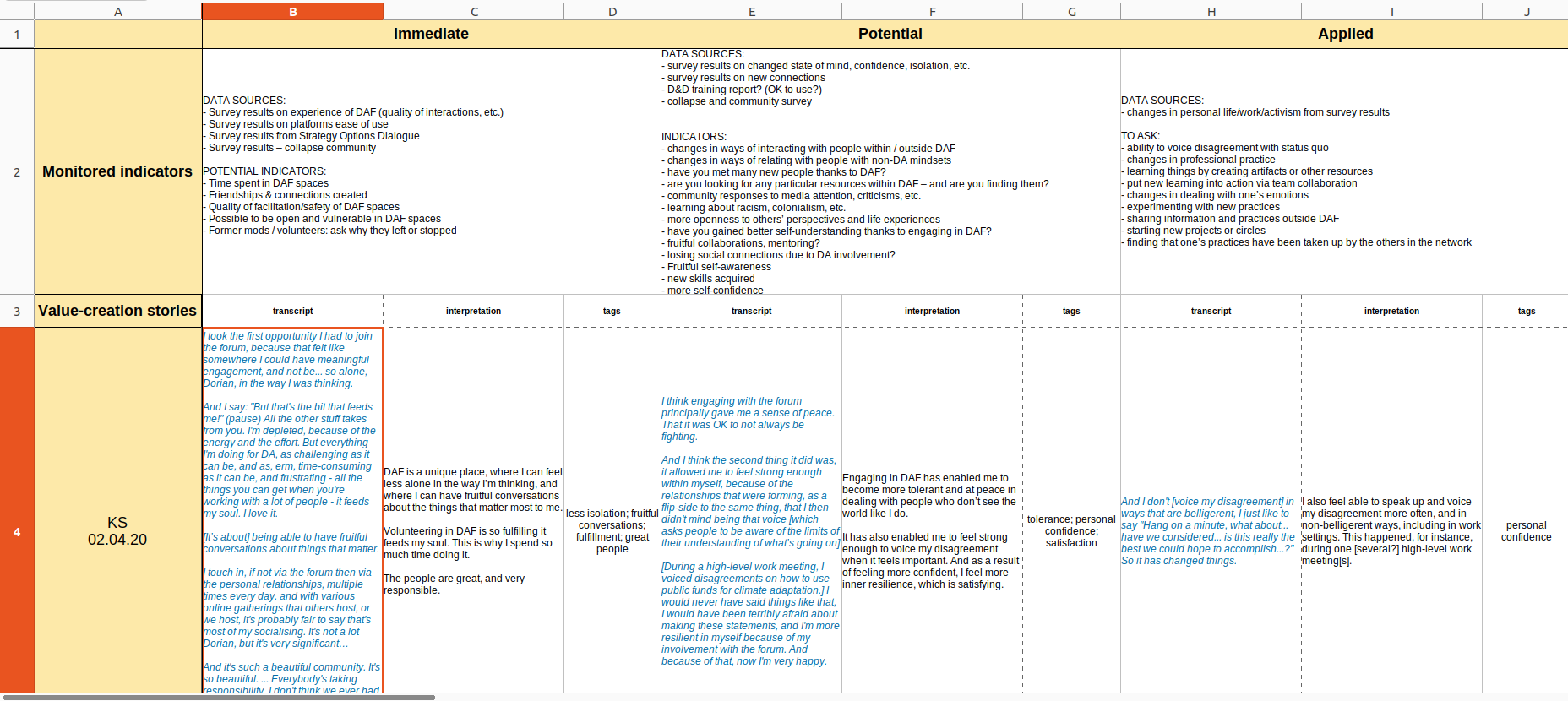

These interviews, which took place in April and May 2020, enabled me to set up a value-creation matrix (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.219) in a spreadsheet, to start integrating indicators and emerging fragments of value-creation stories (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Preview of the DAF value-creation matrix

2.2 Developing an interview process

Interviews took place over videoconference, and were recorded. Ahead of them, I asked interviewees to read the Participant Information Sheet (Annex 3.1) and to send me the “consent email” presented there if they agreed to the conditions listed within.

Conversations were relatively unstructured at first. As a list of potential value-creation indicators started to emerge (Annex 5.1), they provided support for semi-structured conversations, as I started to probe whether these indicators were relevant to the interviewee. I also invited questions and feedback from the interviewee, and engaged my own uncertainty, in the hope of making it possible for each conversation to function as a discrete social learning space. I took notes during the call.

This interview format remained largely similar throughout the rest of the research project, including in the period during which I collaborated with W. Freeman as part of a research team, as mentioned in Chapter 3, and described in more detail within Annex 5.5.

2.3 Evaluation process in three research streams

In order to write Chapter 5 of this thesis and answer the research questions mentioned in Chapter 3, I decided to follow the following research streams as I collected effect data and contribution data within DAF:

- the Diversity and Decolonising Circle;

- the Research Team; and

- the landscape of DAF social learning spaces.

I selected the first two research streams because they concerned social learning spaces that were:

- relevant to this inquiry, due to the strong collective emphasis on learning and change within them; and

- easily accessible for the research team to collect effect and contribution data, as both Wendy and I were regular participants in each of these spaces.

I selected the third research stream out of an intention to consider social learning processes taking place across various spaces and communities of practice within DAF, as a network – in accordance with the general research question guiding this doctoral research.

In-depth reports on Research Streams #1 and #2 are respectively presented in Annexes 5.3 and 5.5. Research Stream #3 is presented in Chapter 5.

For each of these streams, my writing-up and analysis process followed the following broad steps. For more details, please refer to the aforementioned locations.

2.3.1. Identifying participant aspirations

Using contextual narratives and framing processes, as well as survey reports where relevant, I started by forming a broad picture of the aspirations of participants in the social learning space(s) under consideration. This was a crucial step to assess their social learning, especially the creation of Realised value. Annex 5.4 shows my interpretation of participant intentions and aspirations in the DAF landscape as a whole.

2.3.2. Selecting and summarising effect data

I then considered the indicators of effect data that I had been collecting. For Research Streams #1 and #2, this led me to refine the indicators of value-creation I relied on by examining textual sources, and carrying out a Template Analysis (King, 2004, 2012; Brooks et al., 2015). In this process, I sometimes considered complementary effect data sources to create additional indicators of value-creation.

Once I had a refined and consolidated list of indicators for each value-creation cycle in the social learning space(s) I was analysing, I summarised in writing the effect data corresponding to each of these indicators in each cycle, sometimes quoting participants in the process.

In the two in-depth reports (Annex 5.3 and Annex 5.5), I included reflections on any “integrative themes” emerging from the effect data, and cutting transversally across several cycles.

In the case of Research Stream #3, the main sources of effect data were:

- the surveys disseminated throughout DAF;

- opinions voiced in the course of interviews and group discussions;

- personal observations from my part (e.g. on the number of active self-organised groups in DAF).

To write Chapter 5, I brought together effect data from my value-creation matrix corresponding to value-creation indicators, classified as representing “seeds,” “soil” or “sowers”:

- Seed indicators (mostly) represented Potential, Realised and Transformative cycles;

- Soil indicators (mostly) represented Immediate and Enabling cycles; and

- Sower indicators (mostly) represented Applied and Strategic cycles.

As mentioned in Chapter 3, this is an impressionistic framework. In practice, it can sometimes be difficult to classify a given piece of data within one cycle or another (see below).

2.3.3. Preparing the contribution data

Having a consolidated list of indicators in place for each Research Stream, as well as a summary of effect data, I reviewed the value-creation stories I had been collecting (see below), and considered which ones had relevance to the social learning space(s) I was evaluating and to the effect data I highlighted. All stories are compiled in Annex 5.2. Having selected them, I analysed them further, by mentioning in a new column whenever a value-creation cycle referred to one or several of the indicators I had identified. The value-creation matrix was a useful reference point in this regard.

2.3.4. Discussing the contribution data

Finally, I discussed the value-creation stories that were relevant to the social learning space(s) under discussion, and emphasised how they could be integrated – or not – with the effect data I presented. In the case of Research Streams #1 and #2, I also analysed how stories referenced certain indicators more than others, and proposed explanations for this.

In one instance (Research Stream #1 – Annex 5.3), I also considered in more detail the learning flows and loops exhibited by the value-creation stories, and what this could mean in terms of the social learning taking place.

I will now present more fully the process of co-creating value-creation stories.

2.4 The DAF value-creation stories

Value-creation stories are presented in Annex 5.2.

2.4.1 Collection, co-creation and analysis process

Each of the value-creation stories presented in this chapter is the result of a process of co-creation and iterative analysis. For participants other than me, this process generally went through the following stages:

1. Recording the research conversations or group calls on Zoom

The “content matter” for the stories mainly came from one-to-one research conversations, following a semi-structured interview format, and several group conversations, all taking place online. They were carried out using the software Zoom, and the corresponding audio and video feeds were recorded to my hard drive.

2. Producing conversation transcripts

I then imported each new voice recording to the platform Otter.ai, on which I had a paid account. The software produced a rough automatic transcript, which I – together with my co-researcher Wendy - then systematically reviewed and corrected. This led to the production of a first file (the Transcript).

3. Creating and sharing value-creation stories

Having produced a high-quality transcript, I read it and highlighted parts of the transcript that seemed to correspond to a value-creation cycle within someone’s story. I copied each highlighted excerpt into a new text file (the Story Workfile), with one file per person and story, and tentatively coded each excerpt with a “dominant” value-creation cycle or contextual narrative (see below), attempting to adopt a “first-person” perspective as I did so40. Excerpts that seemed to speak to the same rhetorical turn in the story were grouped together into a common paragraph. I then rephrased more concisely each paragraph underneath it, using italics to make sure not to confuse the original with my interpretation. Where there appeared to be “gaps” in the story, or where I felt a lack of clarity, I asked follow-up questions by email.

I kept in mind that to form good contribution data, a value-creation story should have the following characteristics (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, p.208-210):

- A clear protagonist: the story should be told from a first-person perspective;

- A specific case of flow, addressing discrete events, interactions, ideas, changes, etc. and avoiding generalities;

- Conciseness, to avoid losing the listener in contextual details;

- Completeness, avoiding making “magic leaps” and skipping steps in the flow;

- Convincing transitions: the flow from one cycle to the next should be clear;

- Plausibility: a good story should be as realistic and believable by someone familiar with the context as possible.

Once I felt that the story met these six quality criteria, from the Story Workfile, I produced a third file (the Shared Story), containing only my rephrased interpretations of what had been shared with me, along with a story title, subheadings, and an opening quote from the Transcript (leaving out any analytical language, e.g. on narratives or value-creation cycles). I shared this short file with the speaker, along with the corresponding Transcript(s) showing the highlighted areas of text that were “distilled” into that story. My request to each person was twofold:

- To check whether they felt the story I had compiled felt true to their experience and what they had shared with me, along with an invitation to make any necessary changes to it to produce a Final Shared Story;

- To let me know whether they were happy to publish this story openly (after corrections were made) on the Conscious Learning Blog, to share it with the rest of DAF as a network – be it under their own name, or anonymously. When they requested anonymity, I also offered to remove any parts of the Final Shared Story which might lead to others identifying them. If they preferred not to publish their story, I respected their choice.41

4. Connecting value-creation cycles and indicators

Finally, feeling assured that a Final Shared Story had been co-produced, I created a new table from it, with one row per value-creation cycle or contextual narrative. These tables appear in Annex 5.2.

For my own story (Annex 5.2, story #5), I adapted the process above. Taking as a starting point the recording of a research conversation I had with my co-researcher Wendy Freeman on the topic of my own (un)learning, I wrote a new entry in my research journal, in which I reflected on areas of meaningful change for me as a result of my involvement in the D&D circle. Once I was satisfied, I then published my story on the Conscious Learning Blog, analysed it using the value-creation framework, and finally attempted to connect value-creation cycles and indicators.

The tables in Annex 5.2 present the Final Shared Stories which research participants have agreed to publish on the Conscious Learning Blog, or to have included in this thesis.

For Research Streams #1 and #2, I was able to rely on a much more granular list of indicators of effect value than for Research Stream #3 (see these lists in Annex 5.3 and 5.5). For stories which I analysed as part of Research Streams #1 and #2, I considered whether each value-creation cycle referred to one (or several) of the indicators of effect value I was paying attention to for that particular social learning space. Where it was the case, I wrote the corresponding indicator reference number(s) in the fourth column of each table. When I could connect the cycle with no indicator, I wrote a question mark instead.

For Research Stream #3, considering that the analysis was more transversal across various social learning spaces, it was much more difficult to connect effect data indicators with particular value-creation cycles in given stories. Therefore, while I used the indicators provided in Annex 5.1 during research interviews to query potential areas of value-creation, I did not connect these indicators so granularly with the value-creation cycles in the stories.

Table 4 summarises the value-creation stories considered for each research stream.

Table 4: Value-creation stories considered for each research stream

Research Stream |

Value-creation stories considered |

RS #1 – Diversity & Decolonising Circle |

#1, #2, #3, #4, and #5 |

RS #2 – the Research Team |

#7 and #8 |

RS #3 – the DAF landscape of practice |

#1, #3, #4, #6, #7, #9, #10, #11, #12, #13, #14, #15, and #16 |

In the tables of Annex 5.2, I also classified some cycles as “anticipated” (Ant.) – referring to “a cycle that has not happened yet, but that has been explored through imagination” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.257). And in the last column, I indicated whether the cycle pointed to the creation of positive value (+), negative value (-), or to the absence of any meaningful value (0).

Finally, many of these stories can be seen as composed of several shorter value-creation stories, introduced by headers. I refer to these shorter stories as “subplots”42 within the general arc of the person’s story. Sometimes, the learning flows explicitly from one of these shorter stories into a subsequent one; at other times, the flow is less explicit.

2.4.2 Distinguishing between cycles

As noted by other researchers making use of the value-creation framework (e.g. Bertram et al., 2014; Bertram, Culver and Gilbert, 2017), it can be challenging to assign a particular comment or activity to one value-creation cycle or to another. For example, in the D&D circle, a remark stating that one has gained new understanding may be categorised as Potential, Realised, or even Transformative value.

Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner (2020, p.123) acknowledge the difficulty:

Social learning does not necessarily involve distinct phases for each cycle. More than one cycle may be involved in any given activity. The creation of value for different cycles may be intertwined and at times indistinguishable.

Nonetheless, in line with the model’s pragmatist perspective, they argue (ibid.) that

the distinctions are useful theoretically as a more refined model for social learning processes viewed as value creation. In practice the distinction is useful for being more intentional about improving learning capability at each value cycle.

Therefore, my understanding is that while each cycle can be generally characterised by certain dimensions of positive or negative value that it tends to create, and by certain ways of producing this value (ibid, p.76), there is no “cut-and-dried” list of criteria for assigning part of a given story to a certain cycle, and that this categorisation largely rests on the value detective’s understanding of this part of the story within the wider context of the entire story, and of the speaker’s stated aspirations. For this reason, and to acknowledge that “more than one cycle may be involved in any given activity,” I refer to the value-creation cycles in Annex 5.2 as “dominant” cycles in my understanding of the story. In other words, while a certain turn may point to the simultaneous creation of Immediate, Potential and Realised value, for instance, I will code this turn with the cycle that I sense is most prominent for this turn in terms of the story’s value-creation flow.

2.4.3 Cycles and narratives

Besides value-creation cycles, most stories I collected also contain fragments of contextual narratives. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2020, p.230) define a narrative as “a relatively unstructured format aimed at broadly capturing the perspective of the narrator on the history and value of a social learning space.” Such narratives, which paint a contextual picture, should be distinguished from the cycles that provide the gist of the value-creation story, which makes “a very specific claim of contribution.” (ibid.)43

These narratives come in three types (p.152, 230-3):

1. Ground narratives refer to the collective history of the social learning space and what has been going on, including who participates in it, what has happened so far, etc.

2. Aspirational narratives refer to the difference participants are trying to make in the space, and the ways they envision will enable this to happen.

3. Value narratives refer to “general testimonials about how the social learning space is creating value or not at various cycles” (p.232).

Within the context of evaluating social learning, the authors of the value-creation framework mainly view contextual narratives as useful elements for value detectives to better understand the context of the social learning space (p.230), and the narrator’s perspective on it, as a starting point to elicit value-creation stories. Being familiar with most of the social learning spaces explored in this research, I did not collect contextual narratives systematically, but simply chose to keep some of them within the value-creation stories presented below, where relevant.

I should point out that to my knowledge, including contextual narratives within the broader framework of a value-creation stories does not seem to have been explicitly done by any other researchers using this analytical framework; however, I don’t think this compromises the quality of the stories – on the contrary, I believe these narratives function as useful “buttresses” helping to support the articulation of long value-creation flows, such as those depicted in most of the stories presented here.

Because contextual narratives cannot be “boiled down” to a single, “dominant” value-creation cycle, in the tables below I have not associated them with any value-creation indicators in particular.

2.4.4 A landscape of social learning spaces

In the context of the Wenger-Trayner social learning theory, a social body of knowledge can be thought of as a “landscape of practice,” and a personal experience of learning can be pictured as a journey through that landscape (E. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015b). Therefore, in order to better situate the learning in that landscape, I have associated each learning cycle in the stories with the social learning space which I think constitutes the location of that particular moment in the narrator’s flow of learning.

Besides, in order to better distinguish between learning spaces, I have highlighted in green the cycles which correspond to the “main” social learning spaces examined in this chapter. For learning spaces that seemed less important (e.g. due to being overly idiosyncratic), I simply used the generic category “Other.”

As contextual narratives often refer to more than one social learning space, I have not associated them with any space in particular.