Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

Many of us fear that confrontation with despair will bring loneliness and isolation.

On the contrary, in letting go of old defenses, we find truer community.

And in community, we learn to trust our inner responses to our world and find our power.

- Joanna Macy (2008)

Quelles paroles faut-il semer,

pour que les jardins du monde redeviennent fertiles ?11

- Jeanine Salesse (cited in Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2013, p. 268)

In this chapter, I will present findings from the evaluation process that took place within the Deep Adaptation Forum. Using social learning theory and methodologies developed by E. Wenger (1998, 2009) and E. and B. Wenger-Trayner (2015b; 2020), this chapter will assess patterns of personal change taking place within this network. These findings will be discussed using the metaphor of the social learning space as a cultivated field, involving seeds (elements of personal and collective change), soil (conditions enabling learning to take place), and sowers (people who care for the seeds and the soil).

In July 2018, Prof Jem Bendell published an academic paper on the IFLAS blog of the University of Cumbria, where he taught and still teaches (Bendell, 2018). The paper was titled “Deep Adaptation: A map for navigating climate tragedy.” It had been originally written for the Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. It was rejected by the reviewers of that journal, who found unacceptable that the paper didn’t build off existing scholarship – while the paper’s aim was in fact to fill in a gap in such scholarship – and who found it inappropriate, moreover, to “dishearten” readers with its central claim: that the collapse of global civilisation is inevitable, and that it may happen within the coming decade, due to the catastrophic impacts of climate change. In the paper, social (or societal) collapse was defined as “an uneven ending of our normal modes of sustenance, security, pleasure, identity, meaning, and hope” (Bendell, 2020b, p. 4). On the basis of this assessment, Bendell proposed an approach he called the “deep adaptation agenda,” relying on aggressive emission cuts and drawdown (mitigation) efforts coupled with personal and collective attempts at adaptation to the coming changes, based on compassion, curiosity, and respect, which I will introduce in more detail below.

Surprisingly for this kind of work, the self-published paper soon went viral. Within a few months, it had been downloaded several hundred thousand times. Its notoriety further grew as the Deep Adaptation approach was publicly endorsed by leading figures of the Extinction Rebellion movement (Bendell, 2019a; Read, 2019; XR UK, 2019; Bradbrook and Bendell, 2020), and after it was reported on in several major news outlets, such as the BBC (Hunter, 2020), the New York Times (Bromwich, 2020), or Vice (Tsjeng, 2019).

In late 2018, a private sponsor approached Prof Bendell, offering some financial support to launch an initiative building on the wide-reaching impact of the ideas presented in the paper. Bendell agreed, under the condition that the sponsor would have no authority in designing said initiative. Having secured that agreement, he invited several close collaborators to form a Core Team which would help steward this project: the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF). I was one of these people, due to my having provided Prof Bendell with some research assistance during the final stages of writing, as I have described elsewhere (Cavé, 2019a, 2019b).

By early 2020, I decided that DAF could constitute an interesting case study as part of my PhD research. Having obtained approval from the university’s ethics committee, I initiated a participatory action research project within the network. Prof Bendell left the Forum at the end of September 2020, as originally intended. Most of my research happened between April 2020 and April 2022.

In Bendell’s seminal paper and subsequent writings, Deep Adaptation (DA) is presented as “an agenda and framework for responding to the potential, probable or inevitable collapse of industrial consumer societies, due to the direct and indirect impacts of human-caused climate change and environmental degradation.” It “describes the inner and outer, personal and collective, responses to either the anticipation or experience of societal collapse, worsened by the direct or indirect impacts of climate change” (Bendell and Read, 2021b, p. 2).

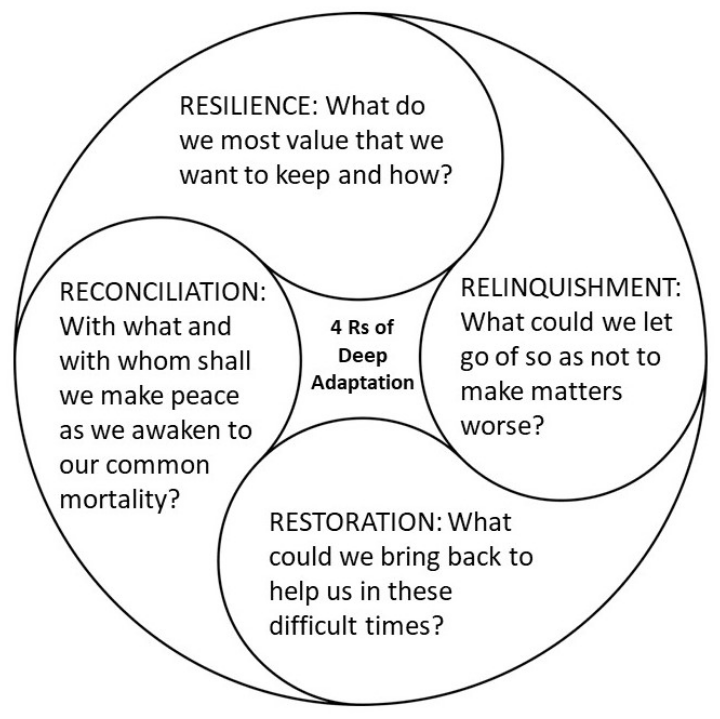

In contrast to more shallow (or mainstream) forms of climate adaptation, DA encourages conversations that go deeper into the causes and potential responses to climate impacts, at personal, organisational, and societal levels. As a way to structure these conversations, Bendell (2020b, pp. 23–24) suggests relying on the following “4 Rs” (Figure 5):

“How do we keep what we really want to keep?” (Resilience)“What do we need to let go of in order to not make matters worse?” (Relinquishment); “What can we bring back to help us with the coming difficulties and tragedies?” (Restoration); and“With what and with whom shall we make peace as we awaken to our common mortality?” (Reconciliation)

Figure 5: The four Rs of Deep Adaptation (source: Bendell & Carr, 2021)

DA is also an ethos (DAF Core Team, 2019b, p. 3), foregrounding the following key values:

compassion: “We seek to return to universal compassion in all our work, and remind each other to notice in ourselves when anger, fear, panic, or insecurity may be influencing our thoughts or behaviours.”curiosity: “We recognise that we do not have many answers on specific technical or policy matters. Instead, our aim is to provide a space and an invitation to participate in generative dialogue that is founded in kindness and curiosity. Valuing curiosity also invites us to challenge some of the ingrained or ‘invisible’ assumptions that underpin our worldview”; and, respect: “We respect other people’s situations and however they may be reacting to our alarming predicament, whether they are first learning about impending collapse or already experiencing it.”

These values were first articulated as central philosophical principles meant to govern the Deep Adaptation Forum (Bendell and Carr, 2019), and later were enshrined in the Forum’s evolving Charter (DAF, 2022a).

As an approach, DA has meaningfully informed studies in various academic fields, including urban planning (Miller and Nay, 2022; Pérez, 2022; Zwangsleitner et al., 2022); sociology (Lennon, 2020; Tröndle, 2021); security studies (Trochowska-Sviderok, 2021); education (von Bülow and Simpson, 2021); public policy (Monios and Wilmsmeier, 2020; Carbonell Betancourt and Scarpellini, 2021); philosophy (Schenck and Churchill, 2021; Roderick, 2022); and performance arts (Stevens, 2019). According to a systematic review of the academic literature which I carried out using the Google Scholar search engine (Cavé, 2022c), by the end of October 2022 Bendell’s 2018 “Deep Adaptation” paper had been cited in at least 296 publications, including 138 journal articles, 94 books, 42 theses, and 22 other documents. All were in English save for 15.

Simply put, DAF is the name that has come to designate the various online platforms and initiatives initially established and managed under the leadership of Prof Bendell and/or the DAF Core Team, since March 2019, as vehicles for DA-oriented discussion and action according to the DA ethos. In the next section, I will return to the question of DAF leadership and my involvement in it.

Defining the nature and purpose of DAF has been and remains challenging, in large part due to three factors:

- Changes in the entity that the name refers to;

- How the project’s form and purpose has evolved over time;

- The project’s open-ended nature.

In the following, I will present an outline of some of the main perspectives I am aware of with regards to the DAF mission and purpose, and how it may be described.

As I explain in Annex 5.4, originally the term “Deep Adaptation Forum” was the name of a particular platform, hosted on the software Ning, designed and launched by the DAF Core Team in March 2019 under the leadership of Prof Bendell. This platform was framed as an international online space in which to engage with DA and the topic of societal collapse from the perspective of organisations and professional fields of activity, and as a place in which mutual support and social learning could happen about these topics (Bendell, 2019c). However, the term quickly grew to cover all activities initiated by the DAF Core Team, as a central organisational body, through the platforms and communication channels available to us at the time – including the Ning platform, but also a Facebook group, a LinkedIn group, a YouTube channel, a newsletter, etc. In order to reduce the confusion, the Ning platform was renamed to “the Professions’ Network of the Deep Adaptation Forum” in October 2019.12

Furthermore, DAF’s official framing has also evolved since its creation. While the project was originally focused on initiating conversations within professional fields of activity, a new emphasis on cultivating new forms of relationality gradually came to the fore, which was later complemented with an emphasis on social justice issues (Annex 5.4).

DAF’s original mission statement was first articulated in the Core Team’s “Strategic Overview and Planning” document from August 2019 (DAF Core Team, 2019a), which I view as the first comprehensive expression of DAF’s purpose and strategy, as follows:

The overarching mission of the DAF is to embody and enable loving responses to our predicament, so that we reduce suffering while saving more of society and the natural world. (p.8)

In parallel to these official framings, largely articulated by the Core Team, I also want to honour the perspectives presented by stakeholders less centrally involved in this project. A useful reference point in this regard is “What Is DAF? Five Ws”, a collaborative document summarising the responses of 13 DAF participants to a series of questions raised by a volunteer and answered collectively between November 2021 and December 2021 (DAF, 2022d). These participants included all kinds of constituents mentioned in Section 4 (including myself and another Core Team colleague). Regarding the purpose of DAF, responses were summarised as follows:

To connect people in a space where they can learn to reorient and respond to collapse with love and compassion, discuss freely and accompany one another on an emotional journey and in projects. (p.1)

The nature of DAF itself has been articulated in a variety of ways. From the beginning of the project until the time of writing, DAF remained an unincorporated entity. Legally speaking, it may be defined as a project of the Schumacher Institute, the registered UK charity acting as DAF’s main fiscal sponsor.

In the 2019 “Strategic Overview and Planning” document, DAF is described as “a set of communication platforms that enable collapse-aware people to connect internationally, exchange information, and take positive action” (p.4).

Responses to the “What is DAF?” exercise mentioned above referred to DAF as one, or several, (online) “space(s)” (5 times), a “community” (4 times), and a “network” (4 times). They were summarised as follows:

An intentional, self-organising network (and associated community) comprising platforms, people, content, and events for learning, support and action. (p.1)

My perspective is that DAF can be understood as an international (or transnational) network; an online community; and as a complex landscape (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015) comprised of various communities of practice, as defined in Chapter 3.

I view DAF as both a learning and an action network, following the typology put forth by Ehrlichman (2021, p. 14):

Learning networks are focused on connection and learning. They are formed to facilitate the flow of information or knowledge to advance collective learning on a particular issue.

Action networks are focused on connection, learning, and action. They are formed to facilitate connection and learning in service of coordinated action.

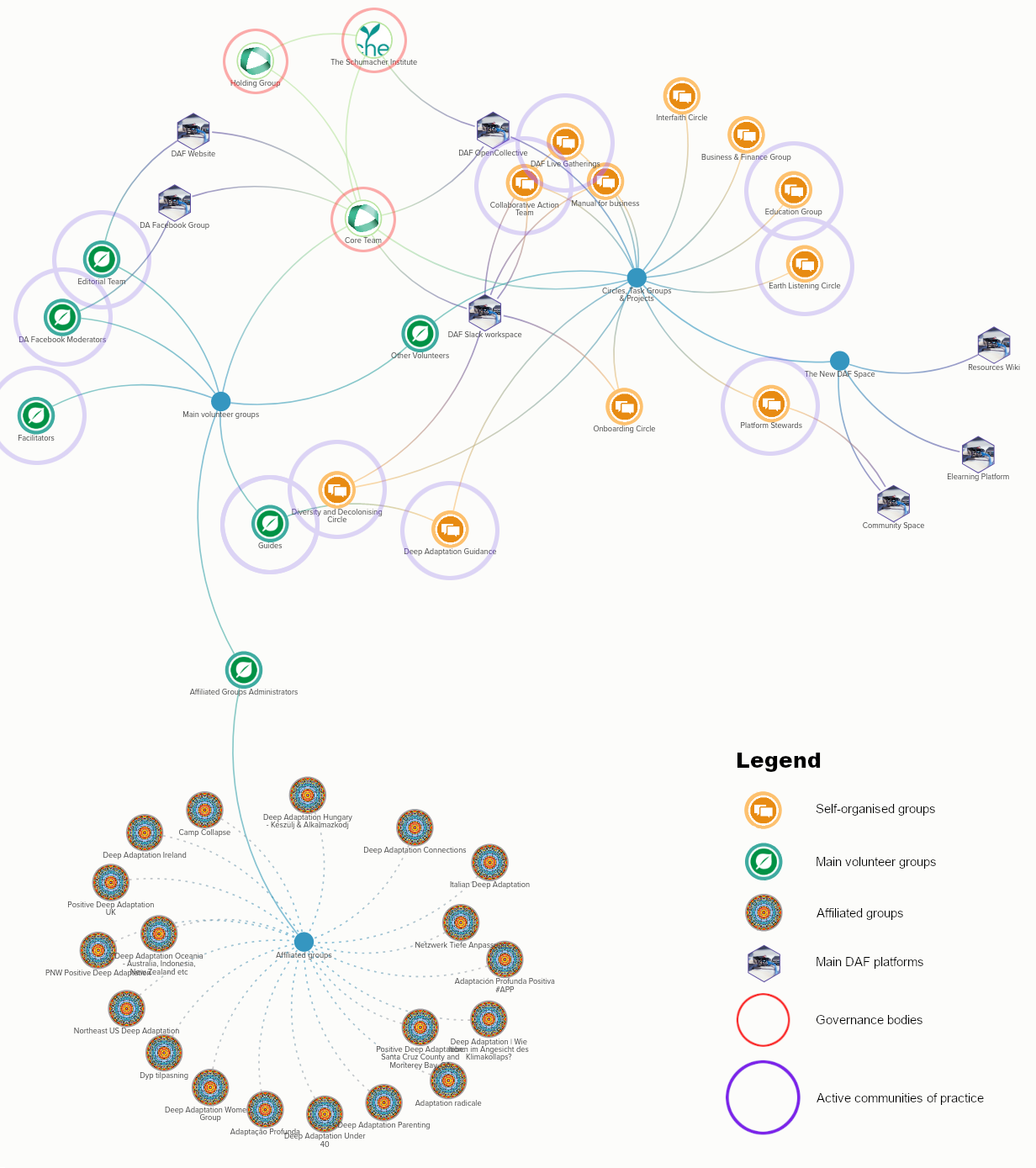

Both of these aspects are embodied in the various communities of practice that have emerged within this network. For example, the DA Facilitators’ group brings together several dozen participants, in order to form “a ‘share and support’ space for people who are hosting, or would like to host, Deep Adaptation gatherings online. The intention is that we can share practices and approaches that embody the ‘Principles of Deep Adaptation Gatherings’, and support each other in holding these conversations” (DA Facilitators, 2022). The Diversity and Decolonising Circle, dedicated to addressing the main forms of separation and oppression that characterise modern industrial societies, is another such community of practice (Annex 5.3).Together, these various communities form the landscape of practice of the Deep Adaptation Forum (Figure 6).13

At the time of analysis, DAF platforms brought together between 15,000 and 17,000 participants, largely English-speaking and living in North America, western Europe, and Oceania. In addition, more than 16,000 mostly non-English speakers participate through groups affiliated with DAF. I discuss DAF membership in more detail in Section 2.4 of this chapter.

Figure 6: The DAF landscape, as of November 2022

As stated above, I was invited in early 2019 to join DAF’s main organisational body, the Core Team, ahead of the launch of the main DAF platforms. Since then and until the time of writing, I have remained deeply involved in this network. As as a paid Core Team member14, I have had to fulfil the various commitments outlined in the various iterations of my memorandum of understanding; and out of personal interest, I have also been investing much of my time and energy in various DAF initiatives on a volunteering basis.

I decided to include DAF into my PhD research as a case study for several reasons.

First of all, by early 2020 it had become obvious to me that through its activities and the relationships it enabled, DAF was in fact becoming an online community that could potentially bring about forms of radical collective change, although of a very different kind than those aspired to within the other community I was studying – FairCoop. Indeed, DAF was a rare example of a network premised on the perspective that radical societal changes were going to happen due to the magnitude of the global predicament: therefore, equally radical action was needed to stave off the worst of these changes. In particular, I was intrigued by the role that cultivating new forms of relationality may play as part of this collective action. I could feel myself undergoing various changes as a result of my engagement, and I was keen to explore whether such changes were also happening to others – and if so, what (un)learning processes could account for these shifts. I discuss some of these changes that took place for me in Chapter 6.

The ethos embodied by my friends and colleagues in DAF also appeared very much aligned with Action Research philosophy as I saw it (Chapter 3). For example, I could see that we were exploring participatory and emergent forms of governance; that we called attention to the somatic and affective dimensions of the person; that we valued collaborative learning; and that the purpose of DAF was emancipatory. This led me to hope that my research project would appeal to others, who might want to join me as part of a research team – which indeed happened.

Finally, my involvement and good relationships with others in the network granted me easy access to other participants. As a result, I was able to set up individual research conversations and disseminate surveys, but also, with my research partner, organise more sophisticated research processes, such as the Conscious Learning Festival activities (see Annex 5.5).

From the beginning, I have been aware that my involvement in DAF might lead me to overlook or downplay the disheartening aspects that, as any human endeavour, it was bound to present. Therefore, I have strived to balance my partiality to this community – whose membership I feel has become part of my identity – with critical attention to its limitations and shortcomings. My aim in this chapter is not to praise or to romanticise, but to pay as much attention as possible to “the good, the bad, the beautiful, the ugly, the broken, and the messed up” in DAF – to use Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s (2021) expression – so that other networks may learn from this example.

In this chapter, I will focus on answering the following questions:

- What are the main “seeds of change” that are being cultivated within DAF social learning spaces? This refers to forms of social learning that appear relevant to DAF participants, in view of the global predicament.

- What are the conditions – or the “soil” - enabling these changes to happen, or preventing them from happening? This refers to the social and material conditions that may help these seeds to grow.

- What kind of learning leadership – and who are the “sowers” – helping to nurture the soil and to sow the seeds? This refers to the persons within a social learning space who enact the clearest forms of leadership in creating the conditions for learning to prosper, within the network and beyond.

In order to answer the research questions listed above, our research team carried out a social learning evaluation process in three specific and interrelated Research Streams within DAF:

- the DAF Diversity & Decolonising Circle (social learning space)

- the research team itself (social learning space)

- DAF as a whole (landscape of practice)

In this chapter, I will focus on Research Stream #3, which addresses social learning in DAF as a landscape of practice. Research Streams #1 and #2 are respectively presented in Annex 5.3 and Annex 5.5. See more details on these evaluation processes in Annex 3.3.

In this section, I will first introduce participants’ aspirational narratives in the DAF landscape of practice; then, I will investigate the seeds of change, enabling soil, and sowers that can be identified within the social learning space. Finally, I will conclude this chapter with a discussion of these results in view of my research questions.

The value-creation stories created over the course of this study constitute an important source of primary data (Chapter 3). These stories can be read in Annex 5.2. For more details on the collection and co-creation of these stories, please refer to Annex 3.3.

First, we should investigate what have been some important aspirations and intentions that participants have been bringing into DAF, as a constellation of social learning spaces and communities of practice. This requires examining both the intentions of the network founder and other conveners, reflected in the discursive framing surrounding the purpose of DAF as it was launched and evolved; and the aspirations expressed by various network participants through time.

For an in-depth discussion of both aspects, see Annex 5.4.

The purpose of DAF was originally introduced by its founder using two main framings: as a network in which to engage with the DA framework and societal collapse from the perspective of organisations and professional fields of activity; and as a space in which to cultivate new forms of relationality, overcoming separation, and fostering compassion and loving kindness. The former reflected a strategic intention to structure the core of DAF activities around a particular platform, initially named “The Deep Adaptation Forum,” and which later became “The Professions' Network.” However, this platform did not fully live up to its mission. Partly as a result, the second framing gradually grew in importance within official communications in DAF. This relational framing was later complemented with a third one, focused on addressing aspects related to the effects of global systemic injustice.

In parallel, participants engaging in the various DAF platforms expressed an interest in a number of topic areas. While some were very much aligned with either of the two main framings described above, others also voiced aspirations that did not readily fit within either of these topics. In particular, more peripheral participants especially expressed a desire for more local community-building efforts, and wished to find more spaces in which to learn about forms of practical preparedness to societal collapse.

This is not to say that none of these other topics have ever been explored and acknowledged as relevant within DAF's official channels. However, they were originally less central within DAF's official framing, which has gradually evolved to incorporate a greater variety of concerns. Besides, the outcomes of various consultation processes between 2020 and 2022 confirm aspirations for more attention to these areas within the network. These outcomes also show the low interest for forms of intervention within professional and organisational fields on behalf of most participants, in contradiction with the network’s original framing.

The history of these strategic consultations speaks to a continued intention, on behalf of the DAF Core Team, to foster self-organisation and support a wide variety of endeavours throughout the network, following a particular ethos - as opposed to driving participation towards meeting any particular set of goals. However, the complexity of this mode of organisation (which breaks from more conventional social movement or non-profit practices) has been reflected in the difficulty for spontaneous groups to emerge and persist in time.

Another important finding, originating from the results of two surveys investigating participants' aspirations, is that intentions for engaging in DAF vary depending on one's degree of involvement in the network. I will return to this more fully below.

What have been the main forms of social learning have taken place within various DAF spaces to meet some of these key aspirations?

A key aspect of the original framing of DAF, as I have shown in the previous section, has been about fostering new forms of relationality.

Within the network, a number of modalities that are directly concerned with this aim have been developed, practised, and promoted, notably within the DA Facilitators online community of practice. In particular, participants in this research project have referred to:

- Deep Relating (DR), which is “a relational meditation practice, or an approach to being in relationship with another person, or group of people, in a way that is grounded in a deep and detailed awareness of present moment experience” (Bendell and Carr, 2021);

- Earth Listening (EL), which is a guided collective meditation centred around the stated purpose of “listening to the Earth” and exploring one’s connection with the wider natural ecosystems of the planet; and

- Wider Embraces (WE), a collective, guided meditation, allowing participants to experience, explore, align and reflect upon different aspects of their being. In this process, one “evoke[s] and explore[s] the physical, the biological, the cultural, the collective and planetary perspectives, which facilitates a greater sense of belonging and alignment between them.” 15

Available effect data regarding DR and EL mostly comes from the Group Reflections Survey (Cavé, 2022d). Through their involvement, participants in the weekly EL circles report having found new ways of being and relating (particularly with regards to other-than-humans and the natural world), as well as more self-understanding and personal healing, and developed more confidence in practising their truth. Similarly, DR participants said they had found more confidence and self-acceptance, more self-understanding and personal growth, as well as finding fulfilment, and that they had become better able to be present with and relate to others. In other words, participants in these two groups appear to have experienced impactful changes in their relational skills and awareness, and in their well-being.

These respondents also mentioned having started new projects or initiatives as a result of their involvement; having found more clarity as to how to shape their home or work life; and having decided to engage more deeply in DAF.

In particular, according to its facilitators, the EL group has been meeting weekly almost every week since it was first convened (in October 2020). As a sign of its success, other groups using the EL method have been initiated over time, in DAF and beyond, by the original group’s facilitators or others who discovered the modality thanks to them.

Interviewees have testified about the impact that practising these modalities had had on their lives. For example, Dana mentioned the profound changes that their engagement with EL had had on them (Story #10). They said they were now speaking to the Earth whenever they went out into the wild. Besides, taking part in EL prompted them to join a course that played a transformative role in their journey towards healing intergenerational trauma.

Asked what they had been learning through their participation in WE, a regular attendee wrote me the following:

“I am learning to let go my need for understanding and thinking. I am slowly opening to the feeling of being in a new way, for me. Allowing my ego and many voices to quieten, allowing senses to open and reach out and in for expressions that sometimes are not speakable.”

These testimonies speak to the important affective benefits that participants have drawn from their participation, particularly with regards to their ability to become more focused, and present to themselves and others.

As mentioned in the previous section, encouraging self-organisation within DAF has been an important intention of the Core Team since the network’s creation. This was clearly articulated on the DAF website (DAF, 2020b):

DAF doesn’t follow the typical route of identifying a specific professional / stakeholder group to serve. Instead, it responds to rapidly increasing concerns about the risks of climate-induced societal breakdown and Deep Adaptation, by channelling them into networks of peer support. This leads to projects that may not have been imagined at the outset.

This ambition has been materialised in two main ways:

- By creating scaffolding, within the network architecture, allowing for the creation and acknowledgement of self-managed teams or groups;

- By providing occasions for participants to articulate their aspirations to one another, and enlist others in the pursuit of common projects or other aspirations.

What seeds of change have been created as a result?

Self-organisation scaffolding in DAF has taken three main forms: task groups; circles; and crews. Task groups (TGs) are a mode of organisation introduced through the Ning platform in April 2019. Any platform members could mention their TG idea in a dedicated space on the forum, and invite others to join them. Once three members had agreed to collaborate, they would be invited to sign an Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with a representative of the Core Team. Following the 2021 Strategy Options Review (see Annex 5.4), a new scaffolding was introduced: circles. Circles are similar to TGs, except that instead of a formal MoU, initiators are invited to a open conversation with the Core Team, leading to a public disclosure of the circle’s remit and intention. Thirdly, to acknowledge the importance of groups self-organising in a more informal way, the concept of crews was introduced in DAF in 2022. Contrary to TG or circles, crews are described as small (from 3 to 7 participants), informal groups, meeting regularly, and which might work on collaborative projects but also simply engage in mutual support or other kinds of discussion (DAF Core Team, 2022d). The concept was borrowed from the Microsolidarity framework (Bartlett, 2022).

A final element of scaffolding is a monthly meeting, co-facilitated by a volunteer and two members of the Core Team (including myself), which aims at enabling mutual support and capacity-building among participants in the process of forming (or taking part in) a crew.

In order to give more visibility to DAF participants’ respective intentions, facilitate the building of trust and the creation of relationships that may lead to self-managed teams forming, online events using an “open space technology” format are regularly organised in DAF. The first series of online open space events were convened by volunteers (with support from Core Team) as part of the 2020 Strategy Options Dialogue. While these activities were primarily about inviting DAF participants to express their wishes as regards the future of the network (see Annex 5.4), they also led to the building of relationships between attendees that gave rise to certain TGs (such as the D&D Circle).

Thereafter, between July 2020 and July 2022, 10 other open space events were organised, mostly facilitated by volunteers forming part of the Collaborative Action Team – itself a self-organised crew. These events attracted registrations from over 300 different participants, many of whom were not active within DAF.

In spite of the efforts mentioned above, it appears that few self-organised groups have succeeded in maintaining their efforts in time. Besides, efforts aiming at supporting the creation of more circles and crews have led to little engagement so far. It is therefore tempting to conclude that DAF has failed to become a self-organising network or community – i.e. one in which “complex interdependent work can be accomplished effectively at scale in the absence of managerial authority” (Lee and Edmondson, 2017).

Nonetheless, literature on self-organisation in open sociotechnical networks like DAF (Massa and O’Mahony, 2021) points out that such ways of organising tend to take time to emerge, not least due to most people’s lack of experience in this domain. In this regard, it is worthwhile to consider encouraging signs that the practice of self-organisation may be slowly spreading through DAF.

“[Thanks to] many conversations [I’ve had in DAF]... I’ve learned that our way of doing things [in the Collaborative Action Team] is spreading within DAF. I notice, for example, how the Business and Finance group leaders now announce their events as ‘Zoom sessions in an open space context.’ I’ve also heard of teaming processes being used more deliberately, for instance in the DA Facilitators’ group. Now, DAF feels more self-organised, more adaptive and focused on small collectives.” (Story #11)

The testimony above was provided by one of the DAF volunteers who, together with other members of the Collaborative Action Team, has been most instrumental in spreading self-organising practices – such as “teaming,” i.e. working in small teams – within DAF. He points out how the practice of allowing emergent groups to form using the open space format has also been applied within meetings of various interest groups in DAF.

Other volunteers mentioned having become better at teamwork since joining DAF, such as David (Story #15). Sasha and Wendy, two volunteers who co-founded the D&D circle (Story #3, cycles 10-13; Story #4, cycles 4-6), mentioned how the scaffolding and support provided by the Core Team, and the know-how shared by the Collaborative Action Team, were instrumental to the circle getting started. As for Matthew (Story #12, cycles 4-7), he explained how becoming a DAF volunteer enabled him to encounter collaborators and to co-found the DA Guidance TG.

There are also emerging examples of other generative projects emerging in a self-organised fashion within DAF. Between September 2020 and September 2022, a comprehensive evaluation and evolution of the software infrastructure supporting DAF groups was carried out by a group of over two dozen volunteers and Core Team members, who coordinated their research, testing, and implementation efforts in a self-organised way. The expertise of three participants in the domain of Sociocratic project management, who occasionally stepped in to facilitate these efforts, was critical (which points to the important enabling role of facilitators, which I return to below). Thanks to this project, three new platforms were introduced into the DAF, and an existing one was retired.

In November 2022, a DAF volunteer invited several others to take part in the efforts of a self-organised collective offering support to women in Ukraine who suffered sexual assault (Story #16). Her story shows how the trusting and affectionate connections she had fostered within DAF were critical to this collaboration taking place, as well as her fellow volunteers’ comfort with self-organising.

Overall, it therefore appears that self-organisation – and the skills that support it – are among the seeds that have been consciously, and influentially, cultivated within DAF. While the network remains in the early stages of relying on such practices, their diffusion is taking place and may lead to fuller emergence of circles and crews in the future.

The Collapse Awareness and Community Survey (CAS - Cavé, 2022a) indicates that most DAF participants view societal collapse as a phenomenon that affects (or will affect) the entire world and from which they will not find shelter, and they also think that it has already started. Their predominant affective (somatic, emotional) responses to this assessment include sorrow and grief, as well as anxiety, fear and terror.

In this context, multiple survey results have repeatedly confirmed that DAF plays an important role in its participants’ ability to live with these difficult emotions, and even to transform them.

A large majority of respondents to the DAF 2020 User Survey (DUS – Cavé, 2022b) said they were feeling “less isolated” and “more curious” as a result of their participation in DAF platforms. Many others also reported feeling “more self-accepting”, “less despairing”, “less confused”, “less apathetic”, and “less fearful.” Four in ten respondents also said they had gained confidence in their ability to deal with the future thanks to their involvement.

Over six out of ten respondents to the CAS found some emotional relief and comfort (including acceptance, joyfulness, feeling less isolated, or learning how to better manage their emotions) through their engagement in DAF. In particular, nearly three out of four volunteers actively involved in DAF testified to reaching better acceptance. Nearly three in four CAS respondents had taken practical steps to bolster their personal or family resilience (such as growing food, changing jobs, or moving to a new location); about half of them were engaged in social forms of adaptation, such as local community-building; and nearly half had become involved in moral or psycho-spiritual forms of adaptation, such as being in service to others, engaging in activism, or embracing new priorities in life.

As for respondents to the Group Reflections Survey (GRS – Cavé, 2022c), most of them expressed having reached improved emotional states (such as more self-confidence, personal understanding of one’s needs, or a sense of trust and belonging) as a result of their involvement in DAF groups, particularly EL and DR. Many also found in these groups the inspiration to undertake new personal projects and activities, from anti-racism work to the creation of new educational groups.

Several interviews provided vivid examples of the sense of relief and encouragement that people may experience, upon encountering a community of “collapse-aware” others.

Stuart, for instance, recounted how joining the DA Facebook group helped him to deal with chronic depression, become more open and honest about his emotional state with family and friends, and attach more value to interpersonal relationships (Story #13). This had a transformative impact on his life. Similarly, Matthew found ways to integrate his grief with other aspects of his life through his involvement with DAF, and to better regulate his anxiety (Story #12). Fred said that experiencing deep connection and fellowship with like-minded others in DAF had helped him to pull himself out of his sense of helplessness and hopelessness, and to undertake meaningful new initiatives as a result (Story #7). As for Diana, she mentioned how participating in various events and groups within DAF made her feel relieved and connected; helped her to find generative new ways of engaging with colleagues; and gave her the confidence to finally “come out” about her views on collapse in a public talk, after having kept her views to herself all her life (Story #14).

Therefore, DAF appears to provide many participants with a renewed ability to reach acceptance of the global predicament, to live with the very difficult emotions it may bring, and even turn these into a source of meaningful action in the world. This is another “seed of change” that has been nurtured within the network.

What conditions enabled these seeds to grow and thrive? What elements of “soil” have been most favourable to them in DAF – or, on the contrary, prevented them from flourishing?

In order to explore what conditions participants have found most useful to their personal learning, I will first summarise the enabling factors that were mentioned in respondents’ answers to several surveys, as well as those mentioned in various reflective conversations taking place in DAF. Specifically, I will draw from the following data set:

- Responses to the Group Reflections Survey (Cavé, 2022c), from participants in the Earth Listening (EL), Business and Finance (BF), and Deep Relating (DR) groups;

- Responses to the Radical Change Survey (RCS – Cavé, 2022c);

- Responses to the DAF 2020 User Survey (DUS – Cavé, 2022b);

- The transcript of the Conscious Learning Festival closing call from October 8, 2021 (CLF); and

- The results of my investigation of social learning taking place in the D&D circle (Annex 5.3)

I will then turn to factors that have been mentioned as disabling. I will draw these from the following sources:

- Responses to the DAF 2020 User Survey; and

- Interviews with nine DAF participants.

For both enabling and disabling factors, I will then examine the extent to which this effect data corresponds to contribution data provided within value-creation stories.

Whether asked about their experience of engaging in a large group, such as the DA Facebook group, in smaller groups or circles – like EL or DR – or in DAF at large, participants’ comments on what aspects had been most helpful to their learning displayed a certain amount of consistency. Table 2 summarises the factors mentioned in the data set.

Table 2: Enabling factors in DAF

D&D |

EL |

BF |

DR |

RCS |

DUS |

CLF |

||

Design of the social learning space |

Clarity of purpose and clear principles of engagement |

X |

X |

X |

||||

Presence of facilitators and moderators |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

A stimulating and informative space |

X |

X |

||||||

Regular meetings within small groups |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

Relational and somatic processes and modalities |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

Group culture and atmosphere |

A safe space, trust, possibility to make mistakes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

A focus on cultivating relationships |

X |

X |

||||||

Enjoying the company of one’s fellow participants |

Finding like-minded others, cultivating belonging |

X |

X |

X |

||||

Diversity of participants and perspectives |

X |

X |

||||||

Helpful and inspiring fellow participants and role models |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

These enabling factors can be grouped in four main categories, which feed into each over or overlap with one another to a large extent.

Participants valued DAF social learning spaces that had a clear purpose and focus, as well as principles of engagement known to all. DA Facebook group members, for example, frequently mentioned their appreciation for the clear focus of the group expressed in its guidelines document (e.g. it is not about discussing climate news). The presence of moderators – like in the Facebook group – or facilitators – like in smaller groups like EL, BF and DR – helping to keep conversations “on track” was also often positively remarked upon. Clarity of scope and facilitation were also considered helpful in terms of keeping discussions stimulating and informative, and thus for them to function as vibrant learning spaces.

“I found that the [Facebook group] moderators worked hard, and were doing a very good job at modelling certain ways of being. They helped to keep the group civil, kind, and loving.” (Story #13).

Within smaller DAF groups, regular video calls (on a weekly, biweekly or monthly basis) tend to be the norm. Several participants valued the feeling of continuity created by such a meeting rhythm, which enables attendees to build strong relationships over time, in space of geographical distance. Both Fred (Story #7) and Dana (Story #10) remarked on the importance of such regular meetings to build relationships, work on difficult emotions, and practice new kinds of relationality.

It is customary, in most DAF online calls, to begin the meeting with a moment of collective “grounding” or “presencing” meditation (see Annex 5.3). This is followed by “check-ins,” during which every participant shares a few words about their current physical and affective state, and any other comments about what may be going on in their lives. Calls usually end with “check-outs” in which people express how there are leaving the meeting.

David (Story #15) mentioned that following initial annoyance at these “woo-woo” rituals, he discovered their “critical” importance: “First, we have to connect as humans, otherwise the rest of it is useless.” To him, it is a “unique” aspect of DAF that “these practices are part of the culture, and they successfully reveal the humans who are involved.”

Participants who regularly take part in DAF calls, for example as part of their involvement with a particular group, have tended to mention such relational and somatic modalities as particularly useful to their learning. Within groups like EL or DR, most of the meeting time is in fact dedicated to engaging with such processes (Cavé, 2022c). Speaking of his experience as a participant and facilitator within several of these groups, Nando said:

“Such gatherings and experiences have had a deep impact on me. My participation in them has changed how I relate with reality, and it is also changing the way in which I express myself about our predicament - more and more, I stress the need to approach these questions from the point of view of feelings and relating.” (Story #9)

DAF participants often mention the importance of psychological and emotional safety within discussion spaces. This sense of trust in other participants is fostered through group agreements16, and various textual reference points laying out the ethos in which discussions should be taking place – such as the DAF Charter, or the Deep Adaptation Gatherings Principles, which invite participants to “return to compassion, curiosity and respect.” Safety is also encouraged by a group culture within DAF which aims at making “everything welcome,” including difficult emotions, and at being forgiving of one’s and others’ mistakes. Moderators, facilitators, and other respected members of the community, play an essential role in modelling such behaviours.

“A culture of being able to name what you're observing is really powerful in any group I think, permission for a member to say, 'I'm noticing...' or 'I feel...' and be able to actually speak it into the space, is really powerful.” (D&D Circle participant)

Another enabling element, referred to particularly by members of the D&D circle and the Collaborative Action Team, is that of encouraging participants to dedicate special care, time, and effort, to sustaining and nurturing interpersonal relationships within the network. On occasion, this may mean setting time aside to work through tensions and conflict, be it happening between oneself and another person, or between other members in one’s group. See Annex 5.3, Section 2.2.4 for an example of a conflict resolution process within the D&D circle.

“The conflict-resolution process that I went through, for some conflict that I was involved in... enabled me to see myself from an outsider’s perspective, and gave me deep insights into how different people with good intentions can approach the same situation.” (Story #4)

DAF participants often express their sense of deep gratitude for having found like-minded others, with whom they can share a sense of belonging and community. For many, this is because no one else around them has an interest in the topic of collapse; for some, the sense of belonging may be linked with an even more specific group focus – be it connecting with the Earth in EL, or engaging with issues of systemic injustice in D&D. Enabling factors mentioned above are likely essential in fostering such feelings of community and belonging.

“I feel part of a community of people who are loving and with whom I'm on the same page. This feels extremely rewarding.” (Story #12)

However, this sentiment does not have to mean feeling part of a monolithic, homogenous collective which erases personal differences. In EL as in the DA Facebook group, participants remarked on the insights they gained from encountering a diversity of opinions and perspectives.

Finally, being in the company of others who are trying to be caring and helpful toward one another is also often mentioned as an important enabling factor. Among these important fellow participants, the presence of “key enablers,” in other words “elders” or “mentors” who have been in the network for longer than oneself, or who may have struggled with difficult questions that one is also facing, can also be a source of courage, insights, and inspiration.

“I received important mentoring from Nenad and Kat in the Community Action group that helped get [D&D] going.” (Story #3)

What conditions may hamper social learning from taking place within DAF groups?

DUS questionnaire respondents, asked to assess the usefulness of two main DAF platforms (the DA Facebook group and the PN), tended to have a more favourable opinion of the former than of the latter (Cavé, 2022b). Their feedback revealed various issues with both of these platforms as mediums of communication. However, their observations focused on different aspects: while PN users mentioned specific limitations with the software Ning, several Facebook users stressed that the platform was problematic for deeper socio-political reasons, including the way it functions as a social media platform.

“I do not find [the PN] intuitive nor easy to navigate or use. If I were on it daily, it would of course be better. But for light periodic use which is all the activity actually warrants so far, it's like a re-learning session every log-in.”

“I wish [DA] wasn't on Facebook. I am considering shutting down my account.”

Other respondents also mentioned limitations that had to do with the social structuring of such platforms. For example, several PN users disliked the “slower” and occasionally “over-philosophical” conversations they encountered on this platform, compared to the liveliness and interaction they found within the Facebook group. On the other hand, users of the latter regretted that too many conversations focused on grief instead of more practical topics.

Beyond this general feedback with regards to the functionality and atmosphere within these two platforms, what more deep-seated organisational issues have DAF participants encountered in the course of their participation?

In order to better understand what aspects of DAF might prevent social learning from taking place, the RT interviewed nine DAF participants who were actively involved in the network for a while but who eventually decided to withdraw from the network, or to only engage in a more limited way. Feedback shared during these interviews sheds light on several disabling factors they identified within DAF, and overlaps with aspects mentioned in several value-creation stories.

Vision and purpose

One interviewee, Carla*17 mainly engaged in DAF through the DA Facebook group. She came to the conclusion that it was largely a “support group,” lacking “social vigour,” and which did not help to foster the localised forms of community-building she aspired to. She considered that DAF was struggling to build the capacity to enable more practical forms of adaptation to global disruptions, and gave people “no call to action.” Simultaneously, she viewed the network as attempting to cater to a wide-ranging diversity of needs, without enough focus on a core area of activity.

This criticism of DAF as too dispersed in its purpose, and not enough “action-driven,” has been a recurring theme in various parts of the network since its creation. Another DAF volunteer, Patrick*, also a community organiser, regretted the “philosophical” and “open-field” approach to change promoted in DAF, leaving it up to anyone to decide what to do, instead of galvanising specific change in order to pursue the network’s mission of reducing harm.

Ruth* joined DAF and became a volunteer on the PN with the intention of discussing the global predicament from the perspective of the biosphere, or the planet as a whole, from a deep time perspective – and was disappointed to find that most other participants were more interested in “focusing on humans,” and particularly on “their own survival and that of their family.” She also regretted the lack of collaborative efforts and task-orientation within the groups they joined.

As for Nina*, she was involved both in the DA Facebook group, and as a volunteer on the PN. But contrary to Carla, she decided to leave the former because she felt “attacked” in discussions she raised on the topic of spiritual growth, and like Ruth, she found she had “no patience for people who are trying to save themselves or their children.” As a result, she started to meet and discuss her topics of interest locally with a small circle of friends, on a monthly basis, which she found much more rewarding.

These testimonies show some of the tensions that have been running through DAF with regards to the specific purpose or framing of the network, its mode of organisation, and the theory of change promoted by the Core Team.

Power and leadership

Another set of tensions concerns the forms of leadership enacted by DAF Founder Jem Bendell and the Core Team.

For instance, Carla was disappointed when Bendell stepped down from his leadership role18, and felt that DAF had become “rudderless” since his departure. On the other hand, Nina stopped volunteering as a result of disagreements with Bendell, head of the Core Team at the time, whom she felt was overly restrictive of the efforts made by herself and other volunteers in the group she was part of. Another former volunteer, Michael*, also expressed discomfort with Bendell’s influence in the network, and considered the founder was “clinging to DA” as his “personal brand” instead of allowing for more collective interpretations and shaping of the DA framework.

Others mentioned difficulties in working with, or within, the Core Team. DAF participant Dana* (Story #10) was put off by the “rigid norms” perpetuated by the Core Team, and stopped communicating with the team as a result. As for Heather (Story #6), she said she had “lost [her] job” within the team because other team members were “afraid to confront [her]” on certain work issues. Another former Core Team member, Alex*, mentioned they had struggled with difficult power dynamics within the team, which had not been adequately addressed.

From these stories, one can perceive the difficulties that have been faced by the founder and Core Team in attempting to encourage self-organisation and emergent leadership (see Section 2.2), while often failing to deal generatively with issues of power, boundary-setting, and accountability.

The anti-racism and decolonising agenda

Another recurrent point of tension has concerned discussions of matters of social justice, and in particular, the approach of the D&D circle – whose work has been supported by the Core Team since the beginning (Annex 5.3), and which several members of the Core Team have been part of.

For Dana (Story #10), there was “an absence of critical thinking on the topics of anti-racism, decolonisation, and othering” in DAF, which felt “stifling and dull... and ultimately even limiting of human rights.” Both Ruth and Alex also expressed feeling “alienated” by the “lack of nuance” necessary to account for wide-ranging historical and cultural differences from one country to the next.

On the other hand, Amanda* said she had been “impressed and delighted” when she heard that the D&D circle was launched, but felt her trust in the network weaken upon realising the “disconnect” between the circle’s intentions and its actual practice. As for Heather (Story #6), she considered that DAF should go much deeper in the work of addressing racism, colonisation, and white supremacy patterns, and that more groups should be encouraged to do so. Michael agreed, and considered that DAF spaces were often “too cuddly” for people to challenge one another on such issues and develop more “authenticity.”

It is perhaps unsurprising that the topics of anti-racism and decolonisation – at the heart of “culture wars” online and in many parts of the world – have proved divisive within DAF. However, could it be that these issues might have proven less contentious, had these topics been more explicitly associated with the “Deep Adaptation agenda,” and mentioned as part of the early framing of the Deep Adaptation Forum? Indeed, neither Bendell’s seminal “Deep Adaptation paper” (Bendell, 2018), nor his early articles framing DAF’s purpose, made any reference to issues of social justice (Annex 5.4).19 As a result, it appears that the D&D circle invited conversations that were considered unwelcome by many DAF participants – which is not to deny that the circle might have chosen more skilful and nuanced ways of doing so.

In order to grow, the “seeds of change” described earlier require the right kind of “soil,” but also “sowers” who take care of seeds and soil, and help seeds to propagate. What are the leadership characteristics that these sowers (or systems conveners) embody in DAF? What roles do they play in fostering social learning in the network and beyond?

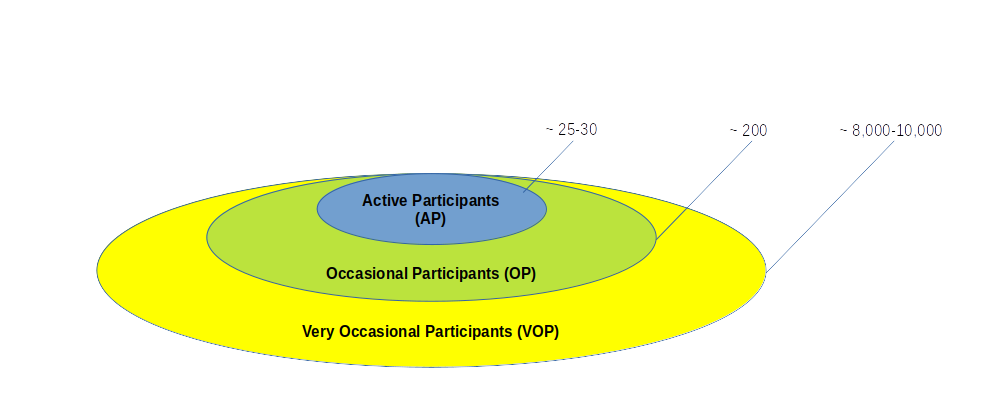

First, let’s examine several broad participation constituencies in DAF. This can be depicted as a series of concentric circles (Figure 7).

Figure 7: DAF participant constituencies and approximate number of people involved (as of August 2022)

An important caveat is that these constituencies tend to be fluid, as a person’s involvement may vary in time. Besides, while certain specific roles in DAF have a clear job description (such as Core Team members, or Facebook group moderators), mostly these broad categories have not been reified so far, which makes it more difficult to have clear statistics on who is actively involved in the network or not. This lack of clearly defined “participation tiers” also allows DAF participants’ perception of these categories to vary. The typology I present below is a reflection of what I witnessed through my participation, and of my readings into the literature about online community management.

At the heart of the graph are Active Participants (AP). This category comprises the DAF Core Team, as well as another two dozen of the most deeply involved volunteers, for instance:

- Facebook group moderators;

- Facilitators of regular meetings (such as EL, BF or DR);

- The Tech Support team;

- The Editorial team;

- Etc.

AP, as the core of DAF, tend to be most involved in various projects and initiatives, including regular group calls, and participate in strategic framing events and conversations. According to statistics compiled by 18 DAF Core Team and volunteers in April 2021, these active participants spent on average 30 hours per month volunteering on the network, with about half of respondents volunteering at least 40 hours per month.20

Occasional Participants (OP) may convene meetings and conversations, but tend to be involved in a more sporadic way. They may be actively involved in a DAF circle or group, which they may have convened, but are less eager to take part in framing conversations, or to take on leadership roles regarding the whole network. Some of them are very active discussants on the DA Facebook group. I estimate that up to 200 participants are in this category.

By Very Occasional Participants (VOP), I refer to DAF participants who do not take on any responsibilities as conveners or volunteers, and are present mostly as participants within the Facebook group. On occasion, some may attend certain group calls, but they don’t become regular participants. At the time of writing (August 2022), according to platform statistics, there had been on average about 9000 active members21 in the DA Facebook group, monthly, over the past six months.

AP are the group of people most deeply involved, at any given time, in sustaining, supporting, and enlivening DAF as a community and a socio-technical network. Therefore, although the vast majority of AP are volunteers holding no formal title, they can be seen as the “network leaders” who steward the network and its purpose, and model DAF norms and values. They are also the “sowers” who nurture and propagate the “seeds of change” described above.

What are the main categories of work accomplished by AP, as they help to convene and structure DAF social learning spaces?

A good starting point for this exploration is the four-part typology offered by Ehrlichman (2021, pp. 60–1). A single person or group may take part in several areas of leadership.

Many AP take on the role of Coordinators – i.e. people who “organiz[e] the network’s internal systems and structures to enable participants to share information and advance collective work” and “establish and maintain network operations, support knowledge management, and assist network teams.” In DAF, such people filter and approve new platform membership requests; inform newcomers and moderate conversations in large semi-public groups; maintain the technical infrastructure; edit regular newsletters; help facilitators publish new events on the DAF calendar; etc.

Facilitators “guid[e] participants through group processes to find common ground and collaborate with one another” and “design and lead convenings, hold space for different points of view, and help conversations flow” (ibid). In DAF, a very active online community of practice – DA Facilitators – exists for this very purpose. Many AP are involved within it, and host regular weekly or monthly gatherings that are free and open to all. Some of them occasionally help with resolving conflict among participants. However, all DAF participants are encouraged to convene and facilitate their own online and offline events, as well as project teams. For example, the 2021 and 2022 “Deep Live Gatherings” hybrid events featured local gatherings convened by volunteers around the world to discuss DA-related topics.

Catalysts craft the network’s vision, and inspire action. As part of this role, they help to “organize new project teams, raise resources, and foster new opportunities to expand the network’s impact.” Thus far in DAF, this has been a role mostly embraced by Core Team members, particularly with regards to fundraising, and considerations of overall network strategy. The Holding Group has also played an important role in shaping issues of vision and strategy.

As for Weavers, they “engage with participants to gather input, introduce participants to each other to inspire self-organization, and build bridges with new communities to help the network grow.” This has been a role embraced by members of the Collaborative Action team, who host online open space events several times a year for DAF participants and other interested parties; and by the volunteers who have been hosting yearly strategic community efforts to decide on the future of DAF (see Section 2.2). But weavers have also emerged spontaneously among existing AP to introduce DAF, or the DA ethos and framework, to other networks and contexts.

However, this typology does not cover all roles taken up by AP within DAF. For example, certain groups such as the D&D circle (Annex 5.3), the RT (Annex 5.5), or volunteers editing the DA Wikipedia page, embody certain forms of leadership in the service of the network that do not correspond to any of those above. Other emerging categorisations (e.g. Strasser, Kraker and Kemp, 2022) provide additional insights with regards to corresponding network leadership roles and practices, but space does not allow to address them here.

Suffice to say that the form of leadership promoted within DAF tends to resemble the network leadership proposed by Ehrlichman (2021, p. 59) – i.e. leadership that is “adaptive, facilitative… and distributed.” Indeed, instead of telling people what to do, or “defining rigid structures and rules,” DAF sowers seek to “connect and collaborate” and “nurture a culture of reciprocity” while “sharing credit and acting in the service of the whole” (ibid, p.60). This fluid approach also corresponds closely to definitions of leadership grounded in Critical Leadership Studies, such as the autonomist leadership put forth by Western (2014) – i.e. leadership that anti-hierarchical, informal and distributed, and based on the key elements of spontaneity, autonomy, mutuality, affect and networks; or sustainable leadership, which Bendell, Sutherland and Little (2017, p. 426) define as “a more emergent, episodic and distributed form of leadership, involving acts that individuals may take to help groups achieve aims they otherwise might not.”

What are the specific intentions and aspirations that move people to become or remain active participants in DAF?

First of all, it should be pointed out that at the time of writing, several active participants received a financial compensation from the network in return for their involvement. Thus far, this has mostly concerned members of the Core Team, like me, as well as a handful of other participants taking care of particular tasks (notably, the administration and development of DAF software infrastructure). All of these participants invoice DAF as self-employed contractors. However, as the pay rate is set to a basic living allowance of GBP100 a day regardless of the role, for a maximum of six to eight days a month, and given that active participants often volunteer as much time as what they are paid for, this financial compensation is unlikely to be a critical incentive for those who benefit from it.

The results of the Collapse Awareness and Community survey (CAS – Cavé, 2022a) shed some light over the motivations of DAF participants. The survey analysed responses from three groups of DAF participants. Although it is impossible to know exactly to what extent respondents’ self-identification corresponds with the typology offered above, due to the survey anonymity, it was distributed in such a way that the following descriptions should be relatively accurate:

- Group 1 was mostly composed of Active Participants (AP);

- Group 2 was mostly composed of Occasional Participants (OP); and

- Group 3 was entirely composed of Very Occasional Participants (VOP).

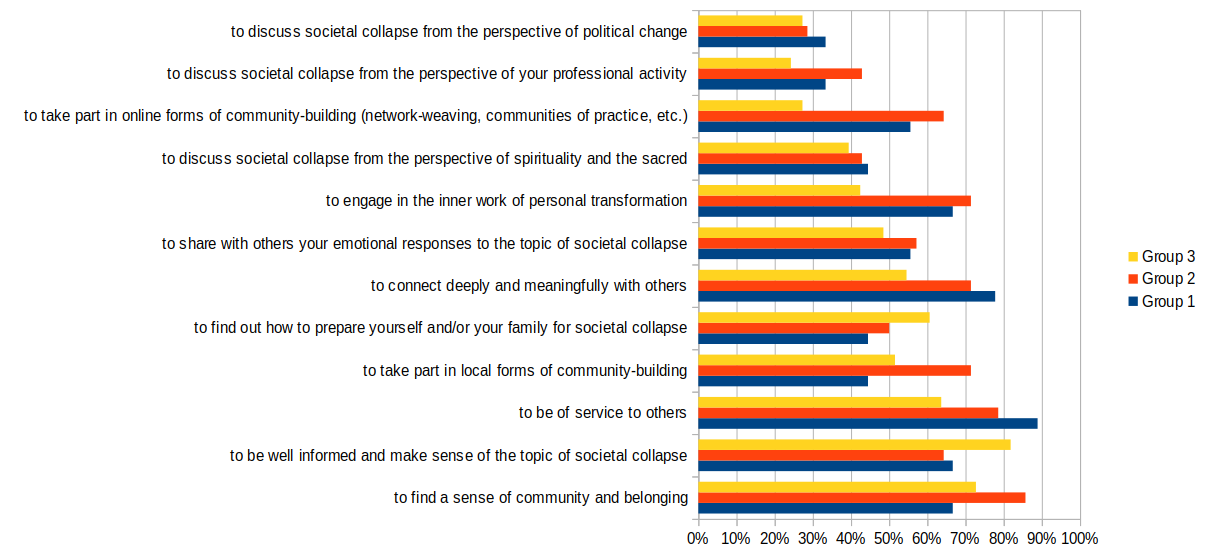

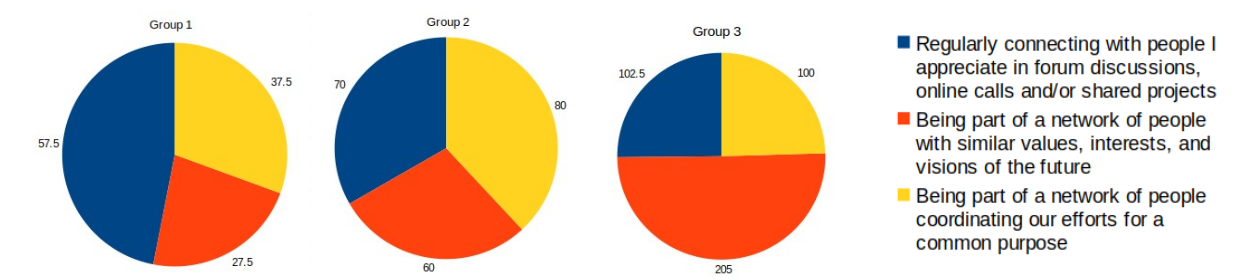

Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the answers of these different participants to questions about their motivation for being in DAF, and the type of community activities they were most interested in finding within DAF.

Figure 8: CAS Respondents' answers to the question:“What is your key purpose (or purposes), currently, as you connect with others in DAF?”

Figure 9: CAS Respondents' prioritised answers to the question: "How important to you are the following aspects of participating in DAF?"

VOP said they were keener to be part of a collapse-aware community, in which they could be well-informed, and learn how to prepare for collapse in practical terms. OP were much more intent to be actively involved in common projects and activities (such as online or local community-building); and AP viewed deeply and meaningfully connecting with others, and engaging in the inner work of personal transformation, as fundamental to their engagement.

Both the AP and the OP were keen “To be of service to others,” and - in equal proportion - “To take part in local forms of community-building,” “To connect deeply and meaningfully with others,” and “To engage in the inner work of personal transformation.” AP and OP were also much more interested in “online forms of community-building” than non-volunteers; but they were less keen about topics like “find out how to prepare yourself and/or your family to societal collapse” or “to be well informed and make sense of the topic of societal collapse” than were VOP. “To find a sense of community and belonging” and “To be well informed and make sense of the topic of societal collapse” were the two purposes that most respondents had in common overall.

Asked to prioritise different aspects of DAF as a community, the three groups of respondents displayed different preferences (Figure 9):

- VOP were overwhelmingly more interested in “being part of a network of people with similar values, interests, and visions of the future”;

- OP had more widely distributed preferences, with slightly more interest in “being part of a network of people coordinating our efforts for a common purpose”;

- As for AP, they largely favoured the statement “regularly connecting with people I appreciate in forum discussions, online calls and/or shared projects”.

These broad differences in aspirations, between the three groups of participants in DAF, prompt the following hypotheses:

- If these three groups represent successive stages of involvement in DAF – from “very occasional” to “occasional” and finally “active” participation – then participants’ goals and interests may evolve as they transition from one stage to the next;

- Alternatively, people with particular mindsets and preferences may tend to become most actively involved in DAF.

Stories from participants who have transitioned from one stage of involvement to the next are informative in this regard.

For example, when David arrived in DAF (Story #15), his intention was only to “reach other people who were considering the issue of potential collapse,” and his interest in this issue revolved mainly around issues of eschatology and spirituality. But following his experience as a moderator on the DA Facebook group, he gradually became intent to find “a new kind of experience, deeper, and more involved in the Forum at large.” He became involved in various other projects and conversations, grew to “[understand] the value of teamwork,” as well as the importance of the relational processes cultivated within DAF. Towards the end-point of his story, David’s aspirations (“to be part of the formation of a truly effective team… to create community...”) appear much more coherent with the main aspirations of other AP than at the beginning.

As for Stuart (Story #13), he joined the DA Facebook group “to discuss matters of civilizational collapse with people, to talk about [his] fears, and find some comfort,” and in order “to learn more.” After a rocky beginning, he found himself acculturating to the group, which brought him much emotional comfort and even helped him overcome an episode of depression. Thereafter, he too became a group moderator. He found that he valued his team members and his interactions with them (“I love the other Moderators. I learn from them, and they improve me as a person”), and his sense of belonging to the team seems to have become an important reason for remaining actively involved in DAF.

David and Stuart both stand as examples of participants who, as they grew increasingly engaged in DAF, saw their intentions evolve and become more representative of those of AP – for instance, wanting to be part of a community of engagement (more than a community of imagination); or becoming more interested in “connecting deeply and meaningfully with others,” “being of service” or “engaging in the inner work of personal transformation” rather than being well-informed. Both of them also seem to have found that a sense of community and cultivating strong relationships have been important reasons for their engagement in DAF over time. Their stories support the first hypothesis above.

However, other AP exemplify the second hypothesis. For instance, Nenad (Story #11) joined DAF with the intention “to support a network” dedicated to fostering “learning experiences” that could bring about transformations in people. Through his participation, he felt he and his collaborators did succeed in supporting positive changes in the organisational culture of DAF. As for him, his intention did not change, although his own learning journey led him to refine his own practice as a “network-weaver.” This is a case of an AP who came into the network with a mindset and preferences which characterise many other active participants.

As can be seen from the other stories presented in Annex 5.2, people become active participants in DAF for a variety of reasons, and each of their trajectories is unique. It is difficult to assess at present whether one of the hypotheses above might be a better reflection of these multiple paths and experiences.

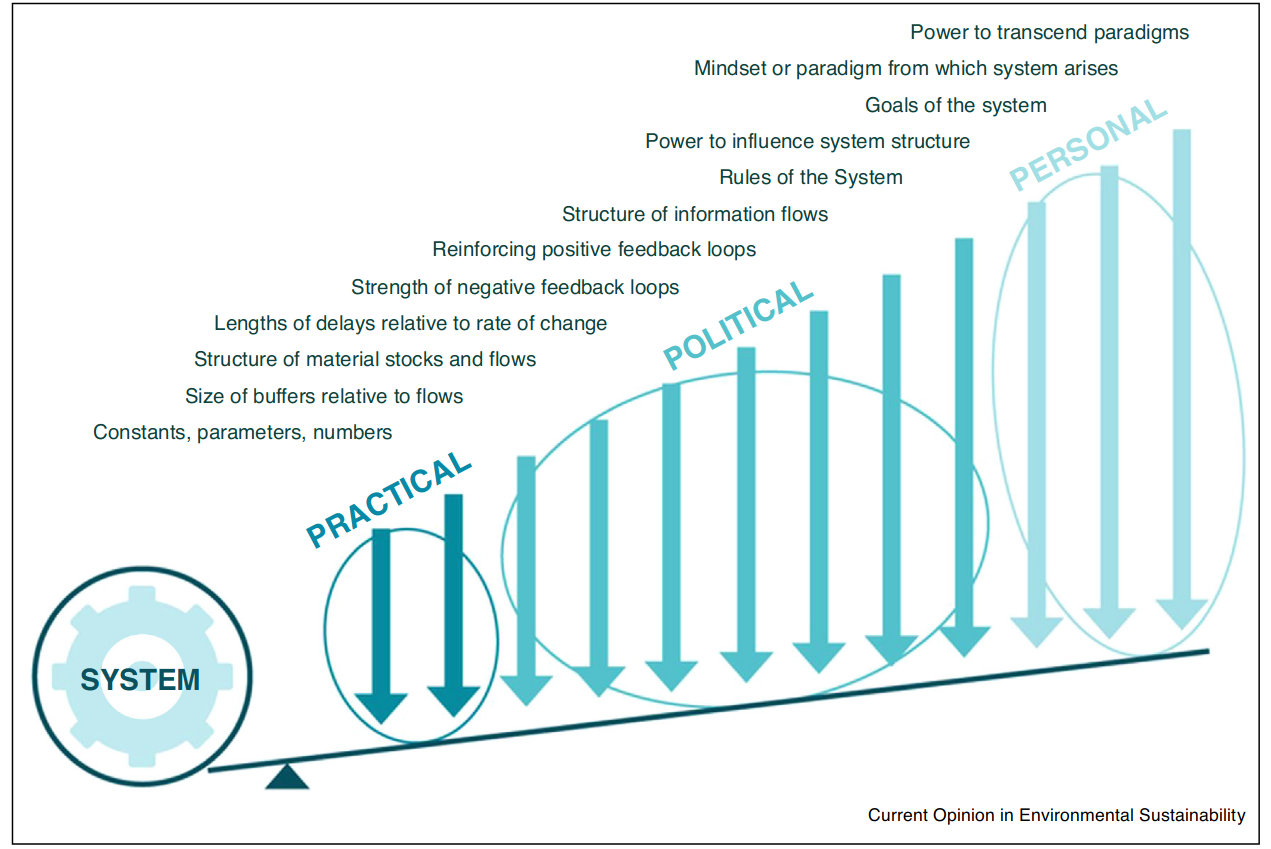

Do DAF participants view their involvement in the network as a way to bring about radical collective change? If so, what kind of change do they aspire to?

Results of the Radical Change Survey (RCS – Cavé, 2022c) help us explore these questions.

The questionnaire invited respondents to take it as a given that radical collective change was needed in the world – and to engage in a thought experiment as to what might be the nature of such a change. In response to this framing, two respondents said that they didn’t feel capable of answering the question. For both of them, this impossibility reflected a lack of conviction that they were able to bring about such change. One of them considered the question irrelevant, in part because they thought nothing may prevent generalised collapse from happening, and in part because they did not seem to view pursuing such change as being intrinsically worthwhile. The other respondents were more willing to engage in this thought experiment, regardless of their belief in the possibility of any radical collective change actually taking place.

I consider that respondents aspired to three main types of radical collective change, which I will summarise here (for more details, please see Cavé, 2022c).

- Orienting towards connection, loving kindness, and compassion towards all living beings

The predominant theme had to do with a new orientation towards collective and more compassionate ways of being and relating. This involved, first of all, human beings adopting a new way of being in the world, grounded in loving kindness. Respondents also linked this theme with the creation or restoration of fairer communities around the world, and with the importance of working on issues of grief and trauma. Another dimension of this new orientation also has to do with finding a new attunement to other-than-humans and the Earth, as well as a deeper understanding of humanity’s place within the rest of the natural world.

“Individual humans are embedded in the ecosystem and how we relate to each other, as well as make a living cannot be separated. Thus, our understanding of the world, our relationships with others, and the way we make a living must all change, radically and collectively.”

- A transformative shift in worldviews and value systems

The second major theme that I identified was about transforming dominant ways of seeing the world and finding meaning. In particular, several respondents noted that this epistemological shift involved truth-telling, in order to reach a recognition of the deep flaws, injustice and destructiveness permeating modern societies, as a result of ignorance, denial and inertia. Respondents also mentioned that this shift in understanding should fundamentally be about modern humans de-centring themselves, and embracing a less arrogant, more biocentric perspective.

“All humans currently engaging in modernity need to unpack our view of how society should be ; assumptions of privileges, assumptions about other human's place in our world - the view or map we have.”

- A radical reshaping of political and economic structures

Finally, respondents also referred to deep changes in the economic and political systems that structure modern-day societies. While some of them seemed open to the possibility of such changes being enacted at a global or systemic level, and thus presumably as a result of revolutionary change and new policies, others spoke rather to a renewed reliance on local, autonomous and democratic communities, and a withdrawal from more systemic concerns.

“I’d like to see everyone’s basic needs met. Of course, this presupposes the elimination of capitalism. When I think about the climate predicament, what comes to me is the phrase ‘extend the glide’ i.e., don’t stop flying the plane even though the engines have failed.”

The questionnaire then went on to ask whether participating in DAF might have been part of such change taking place – and if so, how. While some respondents did not think this had been the case, or were unsure, over two thirds of them answered more positively. Most of them considered that DAF had been useful to help bring about the radical collective change they had in mind, and that they themselves had been able to bring about some of this change through their involvement.

They saw this as mainly enabled by:

- A caring, supportive community;

- Useful relational modalities practised in the network;

- A community of like-minded others for one to emulate;

- The use of the Deep Adaptation framing and ethos;

- Access to useful information and resources;

- Encouraging and inspiring fellow participants.

These correspond to a large extent to the enabling elements already identified above.

It is important to note that by and large, when asked to describe how DAF may have helped to bring about forms of radical collective change, respondents have tended to lay a strong emphasis on individual changes they experienced themselves as exemplars (with less emphasis on collective changes).

Another key finding is that several respondents who self-identified as “actively involved” in DAF (and therefore, presumably, best categorised as “AP” in my typology above), did not seem to find the idea of radical collective change relevant, or had nothing to say about what such change might look like. This could indicate that participants may choose to be actively involved in DAF regardless of any wishes or expectations for social change.

Value-creation stories collected in this research provide several examples of AP mentioning aspirations that correspond to forms of radical collective change mentioned above. For instance, Sasha (Story #3) and Wendy (Story #4) described how their involvement in DAF eventually led them to start the D&D circle, and therefore to invite others in DAF enact a transformative shift in their worldviews and value systems. Several interviewees also stated that the DAF social learning spaces that suited them best were those – such as the Practical DA group – focused on “adaptation at the personal, family, and village/community levels.”

Finally, interviews with two former Core Team members show the strong emphasis they placed on the idea of inviting more connection, loving kindness, and compassion, through their involvement in the Core Team:

“I wasn't particularly keen to explore collapse, or what it means to people. My passion is about exploring how to live and be present with one another, right now.” (Interviewee 1)

“I had a sense of very strong alignment between the DA conversation, and what I wanted my life to be about and with which I have years' worth of practice. And that is, fundamentally, about exploring the ways that meaning-making is carried out in relational spaces, and when people are willing and able to be their most tender, vulnerable selves.” (Interviewee 2)

I have described how many AP have expressed a desire for radical collective change, and considered their involvement in DAF as helping to bring about such change – even if on a small scale. For these participants, how do they envision this change taking place thanks to them and DAF?

Results of both the RCS and the GRS questionnaires (Cavé, 2022c) show that the idea of unlearning plays an important role in this regard, for these AP. I have found that in RCS, three main categories of unlearning were mentioned. In decreasing order, these were: