Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

My awakened dreams are about shifts.

Thought shifts, reality shifts, gender shifts;

one person metamorphoses into another

in a world where people fly through the air, heal from mortal wounds.

I am playing with my Self, I am playing with the world’s soul,

I am the dialogue between my Self and el espiritu del mundo.

I change myself, I change the world.

- Gloria Anzaldúa (1999, p. 9)

In this chapter, I will carry out a cross-cutting analysis of the data presented in Chapters 4 and 5, as I investigate the following research question:

“How do I assess the extent to which the prefigurative online communities I investigated have been (or are being) a source of radical collective change?”

I will answer this question by means of a first-person inquiry, which will lead me to consider how the way I think and feel about radical collective change and prefiguration has been evolving over the course of this research; and what I have been unlearning – if anything – during this process, and how this came about.

In what follows, I will take as starting points various excerpts from the research journal I have been writing over the previous four years. I will explain how I have come to believe that two main aspects are fundamental for prefigurative projects to have the potential to bring about radical collective change:

- adopting a decolonial approach to address the four constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality; and

- cultivating communities of critical discernment.

This will allow me to develop a framework of analysis, through which to examine the data I have gathered about FairCoop and the Deep Adaptation Forum, and consider whether any actual radical collective change appears to have happened in or thanks to these communities. I will close by mentioning some of the main criticisms that decolonial approaches tend to face, and see how they can be addressed.

I will show that a critical part of the answer to the research question above, for me, is that assessing whether an initiative is a source of radical collective change requires one to step away from modern-colonial frameworks of analysis, which are predicated on separation, and on “a series of constitutive dualisms that constrain knowledge (subject-object, mind-body, reason-emotion, nature-culture, human-nonhuman, secular-sacred, and many more)” (Escobar, 2020, p. 86). According to Steiner (2022, p. 257), decolonial perspectives are in the service to life, and thus are fundamentally about relationships, “contrary to modernity/coloniality’s emphasis on seeing things as separate entities and perceiving a separation between them rather than the inherent interconnectedness, interbeingness, and entanglement.”

In the two previous chapters, particularly outside discussion sections, I have strived to foreground the voices and perspectives of the many other people who have taken part with me in this research work. This chapter is much more explicitly focused on my own experience and perspective.

As a result, I am conscious of the risk of making my perspective appear superior or better informed than those other voices we have heard so far. I suspect this is unavoidable, to an extent, considering that I am the author of this thesis. Writing from the position of a PhD researcher grants me particular power to issue statements and pass judgement. This is compounded by other aspects of my positionality, given that I am White, Western, cis-gendered, heterosexual, male, able-bodied, and a quasi-native English speaker, which are aspects that already grant me particular power and privilege. Although I have strived to engage with the other research participants while maintaining relational rigour, by foregrounding qualities of consent, trust, respect, reciprocity and accountability (Whyte, 2020), I realise that there is always the possibility that my activity as a researcher may inherently be a source of violence:

What makes research violent is the way that moral choices, ethical and analytical decisions, representational practices and personal investments of the researcher are secreted away and so are made to appear natural and innocent. (Redwood, 2008, p. 8)

This risk is compounded by the use of academic text itself to present my insights and understandings, within this thesis, considering how “text… can be seen as a cause and a symptom of the disempowerment of research subjects” and “is a barrier to developing connectivities between academia and communities” (Beebeejaun et al., 2014, p. 5). Indeed, the conventions of academic text and the specialist terms it relies on are a source of “power, privilege, exclusivity and exclusion (for outsiders to the academy)” (ibid). I have noticed this myself when sharing chapters of this thesis with interested parties, who sometimes confessed to facing insurmountable discouragement after a few pages, due to the density of the academic style!28

Thus, my wish is that this chapter may help to balance – at least to some extent – some of the power inequalities that have characterised this research endeavour, by providing the reader with more insights into the thoughts and feelings that have accompanied me throughout the past four years, and by being as open as possible about my personal investments.

I also hope that writing these lines can help me become more skilled at centring humour, humility, honesty, and hyper-self-reflexivity, and at disinvesting from some of the arrogance that characterises the behaviour and perceived entitlements of academics within intellectual economies of worth (Machado de Oliveira, 2021); but also to develop a compass that may lead me to bringing more sobriety, maturity, discernment, and accountability into my way of being in the world (Valley and Andreotti, 2021).

To guide me as I write these lines, I will keep reminding myself of four fragments from the text Co-Sensing with Radical Tenderness, by Dani d’Emilia and Vanessa Andreotti (2020):

Face your complicity in violence and disinvest from arrogance, superiority, and status.

Let go of the fear of 'being less', the pressure of 'being more', and the need for validation.

Embrace yourself as both cute and pathetic, be courageously vulnerable.

Turn the heart into a verb: corazonar, senti-pensar.

In Section 2 of this chapter, I will comment on several passages from my journal which I consider attest to my personal (un)learning, with relation to my evolving understanding and feeling into an idea at the core of this research project: that of radical collective change 29. I will bring these excerpts into perspective with the help of the existing literature, mainly from the field of decolonial studies. This reflection will then enable me to assess the extent to which my case studies of FairCoop (FC) and the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF) seem to exhibit elements of radical collective change.

For Lawhon, Silver, Ernstson, and Pierce (2016), unlearning is “a continual, but always partial, reflexive process of identifying ways our conceptualizations of the world are unselfconsciously bounded and invisibly contingent” (p.1615). And for Soto-Crespo (1999), “The process of unlearning signals not indoctrination but rather a critical process of weighing previously acquired beliefs when confronting new ones.” (p.43) These characterisations correspond to the emphasis I wish to lay here on an ongoing reflexive and critical process, with regards to my own beliefs and understanding.

Steiner (2022) defines (un)learning as “the ongoing, never-ending process and cycle of both deconstructing and constructing knowledges, of simultaneously creating new understandings and letting go of previously held understandings” (p.2). I appreciate the bringing together of this double movement of deconstruction and construction, as it speaks to the twin ambitions of the decolonial perspective, which I adopt in this chapter. Indeed, according to Gallien (2020),

decoloniality is best described as a gesture that de-normalizes the normative, problematizes default positions, debunks the a-perspectival, destabilizes the structure, and as a program to rehabilitate epistemic formations that continue to be repressed under coloniality. (p.28)

My only quibble with Steiner’s definition is that the words “knowledge” and “understanding” have very cognitive connotations in English. Beyond the intellectual level, I am keen to investigate how my ways of being in the world are evolving, and what affective and relational processes of (un)learning are involved in this evolution (Stein, 2019).

Finally, I also view (un)learning as a commitment, by more privileged persons, to relinquish aspects of one’s self-image, question one’s assumptions, deconstruct one’s prejudices, and show solidarity in ways that may go against one’s material or reputational interests (Andreotti, 2007).

How have these various dimensions been part of my experience of (un)learning over the past years?

Let us go back to the journey of discovery I sketched out in Chapter 1, in which I described my quest to find a role to play with regards to the global predicament. As I mentioned, back in 2017, I had come to the conclusion that a crucial aspect of radical collective change would be a change in mindsets. But I was lacking a comprehensive way of characterising these flawed “mindsets,” as well as a theory on how they might evolve.

I now feel I have more clarity on both these aspects. My (current, and provisional) understanding is that radical collective change, at the very least, calls for:

- Embodying a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives addressing the constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality; and

- Cultivating this mycelium within communities of critical discernment.

I will address each of these aspects in turn, and draw from my research journal to illustrate how processes of cognitive, affective, and/or relational (un)learning have brought me to these conclusions.

Over the past few years, I have developed a strong interest in mycology. I do not think this happened as a direct outcome of this PhD research, but rather due to a pre-existing curiosity for altered states of consciousness, following ceremonial experiences involving psychoactive mushrooms that I was invited to take part in, ten years ago, in South America. In any case, the idea that initiatives aiming at bringing about radical collective change may be likened to mycelium occurred to me in early 2022, as I was undertaking my first experiments in mushroom cultivation.

One reason I found this image fitting is because I learned that fungi play two essential roles within ecosystems. First, mycorrhizal fungi are a “keystone organism” or even “ecosystem engineers” (Sheldrake, 2020, p. 158) that are critical to to the health of the soil, and to the nutrition of plants, with whom they form indispensable symbiotic relations; they also enable communication and exchange of nutrients to take place between plants and across entire forests (Read, 1997; Simard et al., 1997; Song et al., 2014, 2015). In the words of mycologist Merlin Sheldrake (2020, p.51), “Mycelium is ecological connective tissue, the living seam by which much of the world is stitched into relation.” This mycorrhizal connectivity reminded me of the connected communities with whom I have been carrying out this PhD research. The spontaneous communication and social learning taking place within and between these online communities seems to mirror the enabling role that mycelium plays in communication and exchange of nutrients between plants and within forests.

Secondly, saprophytic fungi are equally vital to the living world as decomposers of organic matter and builders of soil. They “recycle carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and minerals into nutrients for living plants, insects, and other organisms” within natural habitats (Stamets, 2005, p. 29). Furthermore, fungi are also essential organisms for environmental remediation: “They are able to degrade pesticides (such as chlorophenols), synthetic dyes, the explosives TNT and RDX, crude oil, some plastics, and a range of human and veterinary drugs not removed by wastewater treatment plants, from antibiotics to synthetic hormones” (Sheldrake, 2020, p.201). This role recalled the task of recognising the harmful ways of doing, knowing, and being that are characteristic of modern humans, and of finding ways to compost these habits of being.

Fungi are fundamental to the health and flourishing of the living world. I consider that we modern humans, as we face the necessity of (un)learning – decomposing our old, harmful ways of knowing and being, and generating new ones – should look to fungi as our teachers. We need to learn how to form connected, prefigurative initiatives that embody a mycelium of change, at once connective and restorative. In this section, I will outline some characteristics of this potential mycelium.

Let’s start with a brief leap back in time.

Journal entry - Dec.12, 2022

Remember this thought I had back in 2007, Beijing time… Analyse this vision - the vision of the stones lifted up. What that told of me. Critique what there is in me that still perpetuates this masculinist, self-aggrandizing ethos. Not gone, oh no. And this thesis is certainly an outlet for that - although I puncture my own self-aggrandizing by counting on collapse to wipe out electronic servers. … I want to be part of a mycelium of responses now. Happy to be a sower, but only if I view my heart as the field that is being sown, cultivated by all the people in the learning circles I take part in. I am made of other people.

One day in the Spring of 2007, I wondered how to assess whether I was living my life to the fullest. An answer came to me, unexpectedly. It told me that I should imagine the last few seconds of consciousness before my death. If, during this brief moment, I was to “see my entire life flash before my eyes” (following the well-known trope), my life course might appear to me as a landscape, shaped by everything I ever did. And every important deed I ever accomplished would feature within this landscape, under the shape of a big slab of stone, lifted upwards through my efforts and dedication. I decided that living a worthwhile life was a matter of steadily curating this inner landscape, and lifting these slabs of stone.

I now feel ambivalent about this image. Among other things, it centres me as the master landscape gardener of my life, and as the lone heroic figure lifting up heavy stones on my own, like some superhuman Stonehenge-builder. This metaphor is not altogether dissimilar to the idea of social learning being enacted by sowers, disseminating seeds of change and tending to the enabling soil, which I used as a structuring image in Chapter 5. It implies that agency is a mostly individual and anthropocentric quality, and that radical change takes place thanks to these individual acts of agency.

What if I weren’t really in control? What if my very idea of myself – as an autonomous individual, able to pass judgement on what is worth doing with his life, be it lifting up stones or sowing seeds – were a reflection of the culture I have grown up with, a culture which has brought about the planetary predicament? What if I were multiple, and constantly expressing and channelling the dreams, traumas, ideas and affects of every being who ever had a part in shaping my life, whether I am aware of it or not? What if instead of a gardener, I were to see myself as a field, cultivated by a multitude of humans and other-than-humans? And what if a corner of this field was polluted by a large pile of accumulated, unprocessed “shit” (GTDF, 2020a, 2020b; Machado de Oliveira, 2021), its nutrients kept unavailable to the soil that might be fertilised thanks to it?

It is time to do some composting. And I believe this process begins with the four denials that are constitutive of modernity-coloniality, according to the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (GTDF) collective. These denials stand for “what we need to (be made to) forget in order to believe what modernity/coloniality wants us to believe in, and to desire what modernity/coloniality wants us to desire” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.51). As such, they “severely restrict our capacity to sense, relate, and imagine otherwise” (ibid.) (see Chapter 2). They include:

- the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm;

- the denial of the limits of the planet and of the unsustainability of modernity/coloniality;

- the denial of entanglement; and

- the denial of the magnitude and complexity of the problems we need to face together.

I consider that my involvement in the Deep Adaptation Forum – and my intention to undertake this PhD research – came as a result of my growing awareness of the widespread denial of unsustainability, and that of the magnitude of current challenges. And I believe my engagement with these issues has led me to consciously (attempt to) relinquish several beliefs and other mental structures, on the cognitive level – including the theories of sustainability policymaking that I studied as part of my Masters degree; on the affective level – such as dreams of “fixing the world,” or my avoidance of the topic of death; and on the relational level – including the inchoate sense that “someone else will clean up all that mess!”

But it was only later that I started to more consciously address the two other forms of denial, to which I will pay more attention here. I will start with the denial of the historical injustice and systemic violence that are part and parcel of the world I have been brought up in, before turning to the denial of entanglement.

Journal entry - Mar. 3, 202230

March 2020. [At a collapse-themed retreat in Russia] I finish giving the presentation I spent much time and effort preparing, on the topic of societal collapse - how it may happen, what main factors might unleash it, and what Deep Adaptation offers in response. Afterwards, I discover that it went down quite badly with Nonty, who regrets that the presentation focused on the impacts of collapse on rich/industrialised societies. Others wonder whether Deep Adaptation might only be something for rich "global North" people. I feel a bit annoyed, thinking that I only had 20 minutes to talk about a huge topic. But it is true that I did not at all touch on the question of peoples/regions/countries that have experienced collapse in the past as a result of European imperialism and colonialism. Later, as it becomes clear that Nonty feels strongly about the topic, and starts speaking out about it, I approach her to ask more about what she is experiencing in the environmental and ecovillage movement in Europe. She tells me about her experience of everyday racism, ignorance of these topics, and spiritual bypassing. I discover that I know very little about all of this, and acknowledge that over the past 10 years I lost track of that powerful sense of injustice that hit me when I started learning about climate change. … That night, my sleep is very troubled. The following evening, I walk with Nonty along the frozen path... we agree that once the retreat is over, we will look together at how DAF could begin working more closely on such issues.

In this excerpt, I reflect on how my encounter with Nontokozo (Nonty) Sabic prompted me to re-engage with the visceral sense of injustice that struck me when, on the first day of my Masters programme in sustainability, I learned that the countries that were most affected by climate change were the ones that had contributed the least to this phenomenon. Over the following years, perhaps as a result of my social context, I lost sight of this injustice. When I joined the DAF Core Team, in early 2019, I did not notice that our activities were framed entirely around the collapse of the way of life enjoyed by people like my colleagues and I – middle-class people from the Global North. Until encountering Nontokozo, and sensing the extent of the trauma visited upon her, as a Black and Indigenous South African woman, by the centuries of racism, colonialism, heteropatriarchy and exploitation that accompanied European countries’ violent conquest of the world.

A few months later, Nontokozo and I took part in the founding of the Diversity and Decolonising Circle (D&D), whose aim was to reflect on and address issues of systemic oppression within DAF – that is to say, to help more of us, in a predominantly White, Western and middle-class network, consider the fundamental violence and injustice that enabled the rise of industrial civilisation, and that led to global heating and other aspects of the planetary ecological catastrophe (Abimbola et al., 2021). As such, the work of D&D was about squarely facing one of the constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality (Machado de Oliveira, p.51):

The denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm (the fact that our comforts, securities, and enjoyments are subsidized by expropriation and exploitation elsewhere).

As I describe at length elsewhere in this thesis (Annex 5.3), we circle participants soon realised the immensity of the challenge. At times, I have felt powerless and desperate when facing the complexity and intricacy of this history of violence and harm, bewildered by the multifarious ways in which it expresses itself in various personal and social contexts, and shocked by the depth of the intergenerational trauma it has fostered. As a result, our endeavour has been a source of repeated discomfort, disorientation, and even conflict, both inside and outside D&D. But perhaps this was a sign that we were indeed producing “compost” – at the very least, this endeavour seems to have had a generative impact on our lives, and on the lives of others.

I now consider radical collective change as requiring initiatives such as D&D, which function like mycelium that “decompose[s] the debris that other organisms left behind” and “even boost[s] decomposition by providing mycelial highways that allow bacteria to travel into otherwise inaccessible sites of decay” (Sheldrake, 2020, p. 201).

The only trouble with this metaphor is that it may imply that the entity carrying out this composting is working on “shit” that originates from elsewhere, and hide the fact that the flawed humans who compose this entity have their own shit to compost before anything else. As I discuss elsewhere (Annex 5.3, Section 3), the work of D&D could be criticised for having given more attention to this process of personal and collective composting within the circle, as opposed to more politically oriented forms of radical collective change efforts. However, I do not believe this work has been (primarily) performative, and (only) motivated by the desire for forms of “personal development” that are irrelevant to the global predicament. On the contrary, I consider that this process of “inner composting” is wholly relevant to the challenges of our time, and a necessary premise to any outward-oriented action – i.e. challenging the unjust power structures built atop the harmful ways of being embodied in modern humans. It is a fundamental part of the task of unlearning one’s privilege (Spivak, 1988; Moore-Gilbert, 1997; Beverley, 1999; Kapoor, 2004; Andreotti, 2007).

“Modernity is… faster than thought itself, as it structures our unconscious” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.53). As a result, it is inevitable that our desires may include the need to “look good, feel good, and move forward” (ibid, p.113). Such desires may also be at play in my writing these lines. This alone is not a valid reason not to undertake this composting work, but simply points to the need to do so with “honesty, humility, humor, and hyper-self-reflexivity” (ibid, p.304), in order to become more aware of such desires when they emerge, and learn to interrupt them.

My involvement in D&D was also the occasion for me to venture into even more complex territory, which speaks to the connective characteristics of mycelium: the denial of my own entanglement within the planetary organism – the fourth constitutive denial of modernity.

Journal entry - Dec.21, 2021

We trudged up the Pic de Montgros on our snowshoes, the mushrooms and us. At the top, fragments of messages come to me: “Remember what you already know – and trust your gut… Now is a time to make a stand… Life is also full of tragedy… There is nothing to fix… It’s time for you to come into your power – and this power is about reconnecting with your anger, with that wild instinctive side of you.” As a backdrop to this brouhaha: the blades of the wind turbines, shining under the sun, shearing methodically and ceaselessly through the air and the wind – their shadows rolling over the snow and the firs – whooosh, whooosh… shearing through time, shearing through the mountains; but the mountains scoff at them, and just keep on walking.

On the winter solstice of 2021, my brother, my girlfriend and I went on a trek up a mountain in southern France. It was far less snowy than we expected, but we still needed snowshoes most of the way. We decided to give the journey a ceremonial purpose by consuming psilocybe cubensis, a popular type of psychoactive mushrooms. Upon reaching the summit, we found that the landscape was dominated by huge wind turbines. Seeing them, something happened in me. A shock. A visceral, inchoate flow of energy that raged in my chest and my abdomen like lava for the rest of the hike. Somehow, the flow spoke to me.

As I describe elsewhere (Annex 5.2, Story #5), I later reflected on this experience in the light of the work of the GTDF collective – in particular, the book Towards Scarring our Collective Soul Wound, by Cree scholar Cash Ahenakew (2019). It gave me food for thought with regards to the foundation of separation that characterises the modern-colonial world, and the role of knowledge and meaning-making as constitutive of this separation.

Ahenakew conceptualises colonialism as the ongoing maiming of one arm (non-humans, the land, Indigenous and marginalised peoples) by the other arm (colonisers), both part of the same body. This leads to extreme pain for the whole body, although the wounding arm is denying this pain and numbing itself to it, mostly in ways that defend the maiming. Colonialism is thus the source of lasting trauma, “which can only be healed through a renewal of relationships, through a recognition that the wounding and the pain affects us all, and through an acknowledgement that numbing is not healing” (p.36). Unfortunately, the modern onto-epistemology, founded on separation and individuality, prevents this acknowledgement of entangled relationality from happening, and these collective wounds from healing.

Indeed, a key insight from the work of GTDF (Stein et al., 2017) is that “the house of modernity” – which stands for the key social structures of modern existence – is built on a foundation of separability. This foundation both separates humans from the rest of nature (through human exceptionalism and anthropocentrism), and separates human beings and cultures from one another according to hierarchies of worth that represent their perceived utility within the economies of modernity. Separability lies at the core of the violently objectifying and othering31 tendencies of modernity-coloniality, as pointed out by Aimé Césaire (1950) or Gloria Anzaldúa (1999).

How to overcome this foundation of separability? Ahenakew, inspired by Brazilian psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik’s investigation of the Guaraní cosmovision, speaks of the need to re-activate one’s vital compass – i.e. an internal capacity to “be part of and affected by the forces of the world in an unmediated way” (Ahenakew, 2019, p.24). Indeed, this intuitive capacity is limited by an over-emphasis, in modern schooling and society, on the symbolic-categorical compass, which drives a deep need for control of the world (by codifying it in language and knowledge) and of our relationships, and their resulting toxic objectification. Therefore, it is necessary for us modern humans to interrupt our desires for the totalisation of knowledge, and instead, allow the wider metabolism that we are part of to “show us the way” through a recalibration of the intellectual compass. Instead of “creating” new possibilities for less destructive ways of being, we should assist with the birthing process, and avoid aborting these possibilities by smothering them with preconceived ideas (Hine and Andreotti, 2019). This has important implications with regards to the research question I am exploring in this chapter: to me, assessing whether radical collective change is happening is only possible by stepping out of a modernist paradigm, based on this same foundation of separation and the exclusive use of the symbolic-categorical compass.

As Vanessa Andreotti explains,

We [in GTDF] are interested in the shift of direction from the neurobiological wiring of separability that has sustained the house of modernity to the neurofunctional manifestation of a form of responsibility ‘before will’, towards integrative entanglement with everything: ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’. This form of responsibility is driven by the vital compass. It is not an intellectual choice nor is it dependent on convenience, conviction, virtue posturing, martyrdom or sacrifice. (ibid, p.257)

In practice, reactivating this vital compass is very challenging: as suggested by Suely Rolnik, it has to do with a process of decolonising the unconscious (ibid, p.252). It implies a visceral, embodied process – more than gaining new understanding, this decolonisation requires interrupting harmful, addictive habits of being (Suša et al., 2021; Stein et al., 2022). Fundamentally, it is about confronting another constitutive denial of modernity:

The denial of entanglement (our insistence in seeing ourselves as separate from each other and the land, rather than ‘entangled’ within a wider living metabolism that is bio-intelligent) (Machado de Oliveira, p.51).

I originally interpreted what I experienced on that day as hinting at the need for me to become reacquainted with neglected affective dimensions of my being – such as my anger – and with my body. But later, having engaged with the texts above, I realised that this act of interpretation, in itself, was just another expression of the modern urge to make meaning from everything in life, as a result of the dominance of one’s intellectual compass.

The symbolic-categorical compass that drives these desires for the totalization of knowledge and the control of relationships takes up all the space and energy and it does not leave room for the vital compass to be developed and used. If, within modernity, we derive satisfaction from certainty, coherence, control, authority, and (perceived) unrestricted autonomy, we also miss out on the vitality that is gained from encountering the world (and ourselves in it) in its plurality and indeterminacy. Modernity-coloniality makes us feel insecure when we face uncertainty and when our codifications of the world and the stability they represent are challenged. (Ahenakew, 2019, p.24)

Confronting the ontological denial of entanglement is much more than an epistemological necessity, as it would enable modern humans to reacquaint ourselves with the fundamentally interconnected nature of the universe and of our place within it. It is also about healing the wounds of separation. This healing, according to Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, requires “seeing all human knowledge as limited, culturally bound, and equivocal” (2021, p.212), and recognising our ontological entanglement within a wider metabolism. She calls this getting to zero:

In getting to zero we recognize that we don’t know everything, we cannot know everything, we are not a special species, and there is a bio-intelligence in the living planet-metabolism itself that is much older and larger than what human intelligence can fathom. As we start getting to zero, we will need to clear out the things that have cluttered our existence in modernity so that this bio-intelligence can begin to work through us in more profound ways, through the gifts and medicines we carry. (ibid)

There is a direct connection between this realisation – or felt sense – and one’s reorientation toward “fac[ing] and embrac[ing] both unlimited responsibility and accountability”: we become responsible to “continuously compost our individual and collective shit in order to be available to this bio-intelligence” and “sense more deeply our accountability to those, both human and nonhuman, whose lives were taken so that we could live” (ibid.). It is by getting to zero that we may “choose the path of collective healing over the path of collective self-destruction” (ibid.).

I find myself still struggling to fully grasp the implications of the radical relational worldview that underlies the process of decolonising the unconscious, activating my vital compass, embracing indeterminacy and seeking “sense-fullness rather than meaningfulness” (d’Emilia and Andreotti, 2020). It is painfully obvious that my secular upbringing has not taught me to relate to the planet as a metabolism I am part of. (Re-)activating my vital compass is likely to be a lifelong endeavour, which will require much cognitive, affective, and relational unlearning.

For this reason, I have trouble envisioning such a radical reorientation taking place, socially and politically, at the level of individuals or large polities. But my thesis has explored this at an intermediate scale – that of communities. To what extent might the two networks I have investigated be assessed in terms of the metaphorical mycelium described above?

To ask this question is to ask how these communities allow or facilitate ontological decolonisation, the activation of our vital compass, and an unflinching awareness of the historical violence and systemic injustice.

The philosophical foundations of DAF are built on the premise that the collapse of the global industrial society is either possible, inevitable, or already ongoing. This is a clear acknowledgement both of the unsustainability of current social and political systems, and of the magnitude of our global predicament.

Besides, as I have shown in the previous chapter, DAF foregrounds the need for enabling and embodying loving responses – and thus, cultivating new forms of relating – as a primary way to confront this predicament. Within the network, several communities of practice are engaged in the development of modalities, such as Deep Relating and Deep Listening, which invite participants to relate differently to one another (Carr and Bendell, 2021). Others, such as the Earth Listening or Wider Embraces groups, bring more attention to one’s personal and collective entanglement within larger spheres of being, from the planetary to the cosmic (Chapter 5). Finally, the activities of the D&D circle and its associated community of practice directly address the widespread denial of systemic violence and historical injustice (Annex 5.3).

As such, it would seem that DAF provides various social learning and unlearning spaces which together make it possible, for participants, to start confronting each of the four constitutive denials of modernity which I referred to above. My lived experience, and that of my fellow participants in the DAF action research project, attest to the potential for deep (un)learning to occur as a result, and thus, to the presence of potential factors of radical collective change.

That being said, I cannot in all fairness romanticise DAF, or any of the groups within it. Nor do I wish to exaggerate the extent of the change these groups may have brought about (or may yet bring about).

For one thing, and crucially, only a tiny fraction of the 16,000 network participants at the time of writing are involved in any of the communities of practice I mention above. I estimate that no more than a few dozen people are deeply involved in regular gatherings organised by these groups. For all the others, participation in the network is limited to reading and commenting on messages within the DA Facebook Group. Survey respondents have mentioned drawing value from this group, such as emotional comfort, a sense of community, and access to useful information. But a platform such as Facebook, which is engineered to fuel modern addictions and conflict, and to extract as much data from its users as possible (Chapter 1), is hardly a good candidate for cultivating relationality, or enabling a reorientation of the harmful habits of being I have discussed here. My research conversations clearly show that small groups meeting regularly seem to function as a much more powerful crucible for personal change. Currently and as far as I know, no more than a dozen of such self-organised groups are being convened regularly.

As for participants in the communities of practice I mention above, few of them seem to take part in practices that confront all four of the constitutive denials of modernity, which means that many blind spots might remain. For example, engaging in practices focused on reconnection and spiritual oneness without confronting the denial of systemic harm and historical injustice can allow for spiritual bypassing of these issues to take place (Ahenakew et al., 2020). This points to the need for DAF to encourage a wider acknowledgement of the value of these various modalities and groups – and in particular, to centre the recognition of historical harm and injustice as an integral part of DA discourse, which thus far is only starting to happen (Annex 5.4).

The Integral Revolution manifesto put forth by FairCoop (2021) points to an acknowledgement, within the network, of the limits of the planet, and thus of the need for radically new forms of politics and economics. However, there were few signs, within this community, of a deep awareness of the magnitude of the global predicament, of the pervasiveness of systemic harm and the heritage of historical violence, or of the ontological entanglement of humanity within the wider planetary metabolism. On the contrary, an important finding from this case study is that there was little reflexivity in FC around participants’ “ways of being,” or to the quality of their relationships. For several participants, this absence led to important insights, which some said led them to shape differently the social learning spaces of projects they took part in later. But overall, it seems clear that ontological decolonisation was not a form of change sought or enabled by FC. Therefore, in terms of the framework presented above, it doesn’t seem that FC showed potential for radical collective change to take place through its activities.

However, compared to DAF, FC had much more success – for a while – in pursuing another form of collective change: federating decentralised, self-organised groups convened in local settings around the world. I will briefly return to the question of localised groups as potential agents of radical collective change in the conclusion of this thesis.

First, I will discuss the importance of how prefigurative communities are structured, in particular with regards to enabling collective discernment.

A second factor has come to my attention as determining a prefigurative community’s potential to create radical collective change: community structures and processes fostering belonging and critical discernment. This factor plays a containing and enabling role with regards to the first one. In theory, nothing prevents individuals with access to the internet or a reasonably well-furnished public library from starting to face the constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality. But in practical terms, given the magnitude and difficulty of the (un)learning that this entails for an average human being socialised into modern society, I doubt the feasibility of going very deep or sustaining such efforts on one’s own – or the possibility of initiating relevant projects – without the company of dedicated (un)learning partners. What then might be some minimal enabling conditions that may allow such radical change to be undertaken on a collective level, as part of prefigurative initiatives?

My experience has led me to sense-think (sentipensar) that a delicate balance of belonging, space for generative conflict, and emergent leadership, is required for a community32 ecosystem to emerge in which a mycelium of change may grow and prosper. And that the cultivation of critical discernment is an integral part of allowing this emergence.

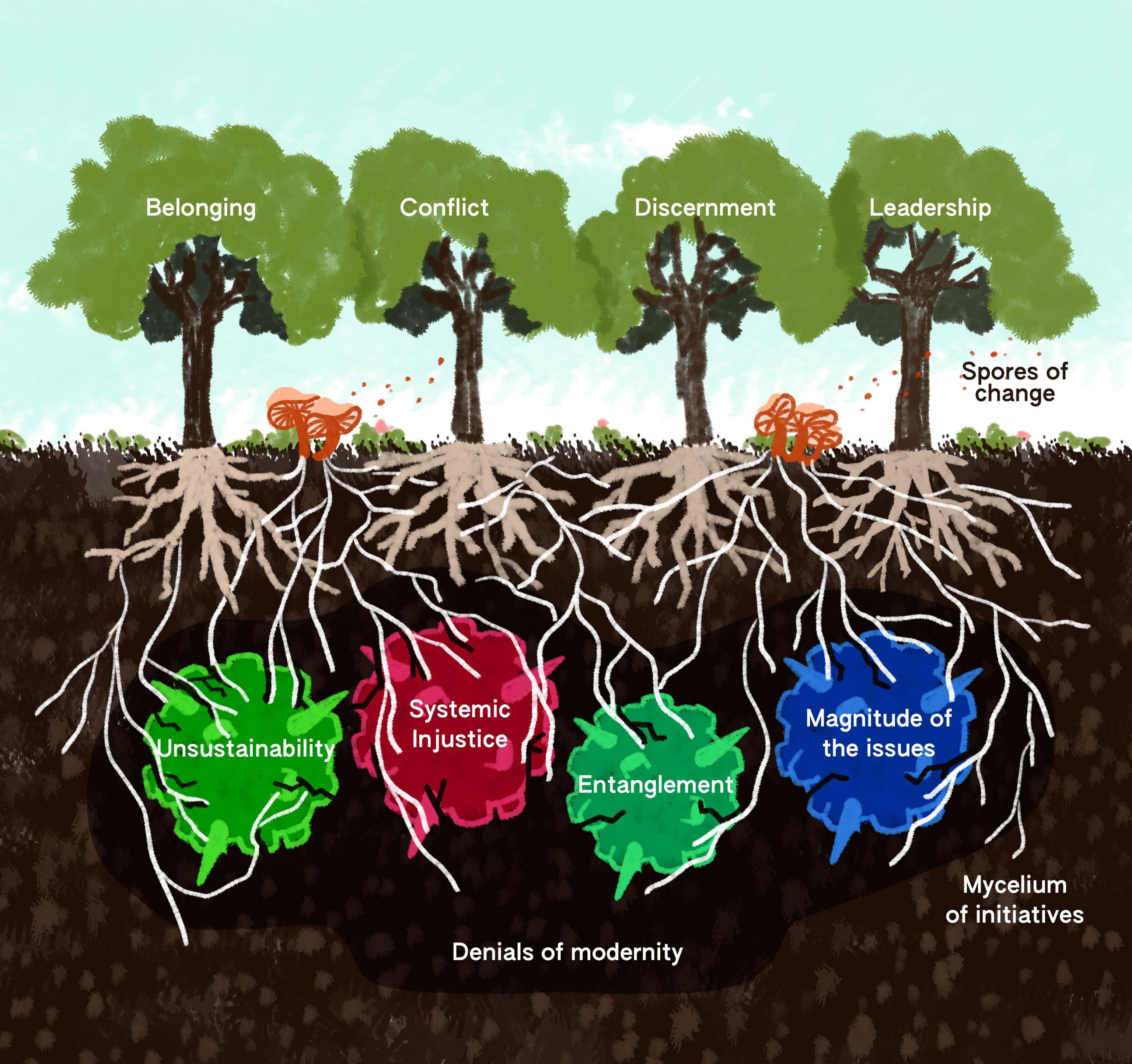

These conditions are summarised in Figure 11. The trees in the image represent these characteristics of generative communities, which live in symbiosis with the initiatives forming a mycelium that slowly decomposes the denials of modernity, referred to in the previous section. Occasionally, mushrooms may sprout from the soil and disseminate spores that will be carried by the wind – or other means of communication – to other social contexts.

I will now turn to each of these characteristics, starting with the cultivation of trust and belonging.

Figure 11: A social ecosystem favouring the emergence of radical collective change in prefigurative communities. Artwork by Yuyuan Ma

Journal entry - Feb.15, 2021

The shittiness of it all. The stories crossing paths, not tallying, only making sense in their own self-contained and self-reinforcing universe of pattern-detection: racism, white supremacy, scapegoating on one side; alliance-building, betrayal, self-victimizing on the other. The carried traumas, wreaking chaos on our nervous systems, befuddling our wisdom and hearts. Where's the exit? And have I learned absolutely nothing from studying FC?! The need to share the stories. To make the space for the stories, to look at them critically.

A running theme in my research journal is about the pain and joys of community and belonging – or the lack thereof. Another is about the confusion and conflicts that occur when very different stories and visions of the world come into contact. How to remain in relationship with someone who does not seem to be looking at the same reality? The question is all the more complex when these relationships are maintained by electronic means, between people who aren’t present to the same local context… especially when the means of communications, in themselves, amplify political polarisation (Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2021) and even create “digitized realms incapable by their nature and design of generating a broadly shared experience of reality” (Sacasas, 2022a) - as mainstream social media appear to do (Chapter 1).

Over the course of my research, I witnessed most of the online communities I was involved with become divided over the question of the legitimacy and usefulness of Covid-19 government policies. Some were torn apart by a lack of consensus on this issue. I also witnessed other spaces become raging battlefields as a result of interpersonal conflict, lack of trust, and poor governance (Chapter 4).

My observations have led me to believe that online communities can provide a sense of trust and belonging that, in itself, helps to reduce stress and anxiety in an increasingly chaotic and unpredictable world (Cavé, 2022a). Such communities can also enable people to lower their defences and engage more authentically with one another. As I wrote in my journal:

Journal entry - Sept.16, 2021

[In DAF] I have learned about how I can better express my emotions, be vulnerable with others, and be heard, in the face of this ongoing tragedy. … I have gained the embodied, active hope that I can be fully present with this predicament that is unfolding, and keep journeying with others through this darkness in meaningful ways.

This is precious. However, the possibility remains that such spaces will “[keep] us in an infantile state where our relational bonds are dependent on mutual coddling” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.157). Avoiding self- and mutual compassion from slipping into indulgence, and cultivating critical discernment collectively, requires being able to speak one’s truth more directly to others. Given the pervasiveness of modernity-coloniality, fostering such discernment feels imperative to any form of decolonisation.

Indeed, according to Jacqui Alexander (2006, p. 281), it is the experience of fragmentation and separation due to modernity-coloniality that produces “a yearning for wholeness, often expressed as a yearning to belong, a yearning that is both material and existential, both psychic and physical, and which, when satisfied, can subvert, and ultimately displace the pain of dismemberment” (cited in Andreotti, 2019). While we modern humans can build new alliances, coalitions or communities, these new polities ultimately reproduce the very fragmentation and segregation they spring from, by reproducing an “us-versus-them” dichotomy and obscuring the interdependence that is constitutive of our existence on this planet.

I believe that in order to potentially bring about radical collective change in the midst of collapse, for instance by enacting decolonial approaches, participants in prefigurative communities need to engage in at least three simultaneous efforts:

- build strong relationships and a solid foundation of mutual trust, which tends to work well within small affinity groups, and cultivate an ethics of care (Gilligan, 1982);

- establish safe enough social learning spaces and communities of practice (Carr and Bendell, 2021), in which participants may stay at the edge of their knowing, and critically examine and discuss what they see happening in the world at large as well as their personal and collective experiments, without fear of compromising their relationships; and

- develop their negative capability (French, Simpson and Harvey, 2009) – that is, the capacity “to live with and to tolerate ambiguity and paradox,” “to tolerate anxiety and fear, to stay in the place of uncertainty” and thereby “engage in a non-defensive way with change, without being overwhelmed by the ever-present pressure merely to react” (p.290).

My research has led me to discover certain modalities that have generative potential in this regard. For instance, paying attention to “hot spots” during meetings can help interpersonal tensions and dissatisfaction to be expressed and normalised (Annex 5.3). Deep Relating is a useful process to examine the stories that are we often reproduce unconsciously in how we think, and what we say or do (Chapter 5). As for small affinity groups meeting regularly, such as microsolidarity “crews” (Bartlett, 2022), they can work as useful containers in which to develop strong relationships, for the productive examination of failed experiments.

It also seems necessary to develop spaces in which to productively examine and work through conflict when it occurs, in order for deeper mutual learning and understanding to emerge – as I have experienced in the D&D circle (Annex 5.3). A number of my journal entries speak to the evolving (un)learning that I believe has been occurring for me, cognitively, affectively and relationally, on the topic of conflict:

Journal entry - Feb. 17, 2021

Choosing not to completely cave in to seductive narratives on any side, and sit firmly (打坐) within the trouble: one of the only ways to keep the chaos from spreading and growing more acute? … Choosing to hold in mind BOTH the very worrying things reported by people about X, the damning litany of [affronts] and suspicions... AND the inability to see X in this light - or only in this light? ...A few hours later… Sensation of a breakthrough. An opening, light streaming in.Reminder to self: LISTEN TO THE BODY. When that contraction in your abdomen tells you, "Go speak to that person" - speak to that person. Do NOT ignore the signals. Maintain the clarity, the listening. The bridge-building.

On several occasions over the past years, as a researcher, as a friend and as colleague, I have found myself “sitting between stories” – between seemingly irreconcilable interpretations of words, actions or events, big or small, and the wider implications thereof. I have felt myself nearly torn apart emotionally by calls to join one side or the other, which sometimes felt excruciating. And while I generally found myself leaning more towards one side or the other, I also feel I have become more skilled at holding within myself these messy, contradictory stories, and at looking for the sparks of provisional truth I could relate to. This was possibly as a result of the attention brought to somatic processes within DAF. Bringing more conscious awareness to my bodily responses – and less primacy to my cognitive processes – is a practice I am keen to explore further.

But I have also been invited to unlearn much of my conflict avoidance, which is a characteristic of white supremacy culture (Okun, no date), and to consider how I tend to ignore my feelings of discomfort within a group or a relationship. I agree with Steiner (2022, p. 273) who states that “Learning to engage with conflict in generative ways is an important skill for delinking from the colonial matrix of power and relinking to life-affirming pathways.”

While it remains difficult for me to lean into conflict, I have become better able at doing so. I give credit in this regard to the explicit agreements made in certain groups I am part of (such as the D&D circle) recognising that conflict is a normal aspect of life, and one that can be a source of deeper trust and understanding when explored with care and respect.

This mutual understanding extends beyond the interpersonal domain. I believe that conflict, when treated as a fertile friction/encounter, can help reveal people’s different exposure to systemic injustice, and their entanglement with different layers of the planetary metabolism. For this reason, it may be a source of critical discernment. But when the conditions don’t allow these conversations to happen, and when people are not willing to “sit in the fire,” communities fall apart and no more (un)learning happens (Chapter 4).

It is important not to confuse interpersonal conflict and institutional violence. But “what we practice at the interpersonal level is important and is part of how we get to larger structural change” (Steiner, 2022, p.276), as other scholar-activists such as adrienne maree brown (2017) have noted. For me, leaning into generative conflict is a primary pillar of radical prefigurative practice.

Finally, questions of leadership and power are crucial to consider closely in any prefigurative community. As I have shown in Chapter 4, influential participants – especially community founders – play a critical role in kindling energy and enthusiasm, as well as in attracting funding and other forms of support. Their role is essential. But clear structures to acknowledge their role and responsibility, and holding them to account, are equally necessary, particularly when a community relies on participatory democracy.

Moreover, communities that aspire to “horizontality” will benefit from embracing a more positive vision of leadership itself – if the kind of change-related initiatives mentioned above are to emerge within them.

Journal entry - July 7, 2021

Again and again ... the same question: What is it that moves people? How to nurture meaningful, purposeful drive and participation with as little pulling and prodding as possible, and with as little command-and-control as possible? How to conjugate energies and bring about transformative change without burning out oneself, or falling into despondent àquoibonisme33? Surely this must be a crucial question for this PhD as a whole? And is this not a question of... leadership?! Loathe as I am to use this word, most likely due to its strong flavour of managerialism…

Since I began this research project, I have overcome the feeling of repulsion that I used to experience whenever hearing the “L-word,” which evoked neck ties and confident business-school smiles. I have discovered that leadership does not have to mean a centralisation of power, exercised in a hierarchical, top-down fashion. For instance, notions of autonomist leadership (Western, 2014), sustainable leadership (Bendell, Sutherland and Little, 2017) or network leadership (Ehrlichman, 2021) are explicitly non-hierarchical, and refer to spontaneous, emergent, episodic and distributed actions that individuals can take in order to help groups achieve their aims (Chapter 4, Section 2.2.4). These forms of leadership feel particularly suited to the “horizontal and intergenerational relationships grounded in commitment, trust, reciprocity, vulnerability, accountability, care, love, and consent” (Steiner, 2022, p.258) that are called for by decolonial approaches to collective change.

Embracing such forms of leadership to encourage emergence and self-organisation is easier said than done. According to community practitioner Alanna Irving, “there is no such thing as self-organisation. There’s only unseen, unacknowledged, and unaccountable leadership” (Bollier, 2022). I now believe that a prefigurative community will harbour more potential for radical collective change to the extent that it values, encourages and acknowledges acts and roles of leadership. I have discovered that there are techniques and philosophies of organising – such as Sociocracy (Rau and Koch-Gonzalez, 2018) or Prosocial (Atkins, Wilson and Hayes, 2019) – that do not require endless meetings in general assemblies, a blind faith in spontaneous self-organisation, or the reliance on hierarchical chains of command. But adopting or imposing such methods wholesale, without consideration of existing norms and ways of doing that may have already organically emerged within a community, may be unwise.

Leadership should also be valued when it aims at enriching the social learning happening within a community. This is the role of learning citizens (Wenger, 2009) or system conveners (B. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015), who broker new relationships and learning partnerships, “reconfigure social systems through partnerships that exploit mutual learning needs, possible synergies, various kinds of relationships, and common goals across traditional boundaries,” and “view their work, explicitly or implicitly, as an endeavor to generate new capabilities in their landscape” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015, p.100). I have found that taking on such a facilitating role, and focusing on relationship-building in both my research and my work, has helped me overcome some of the embarrassment and lack of legitimacy that I used to experience in starting a new initiative. This was doubtless due to my experiencing a sense of safety and belonging in DAF. Conversely, it has also helped me let go of the feeling that leadership is necessarily heroic and self-sacrificing: one can be in service to a group or project while still establishing boundaries and engaging in self-care. As a result, it has become less daunting for me to convene groups and projects, most of which have been useful collective change experiments for myself and others (including many generative failures) – such as the Conscious Learning Festival in DAF (Annex 5.5).

Finally, placing an emphasis on emergent and distributed forms of leadership does not mean that everyone in a community is at the same stage in their decolonial practice. As I discuss elsewhere (Annex 5.3), the presence of experienced “key enablers” helping to orient and stabilise the social learning within groups – for example, on the topic of conflict – can be extremely helpful. However, such forms of learning leadership do not imply that such individuals should have more power over agenda-setting or decision-making.

To what extent do FC and DAF constitute examples of communities fostering belonging and critical discernment?

As I show in Chapter 4, FC was initiated on the basis of a radical acknowledgement of the failings of financial capitalism and nation-states. It aimed at facilitating an “integral revolution” that would lead to the replacement of unjust systems from the bottom up, notably thanks to innovative currencies and an alternative grassroots economy.

However, it seems that this community did not create enough space for the cultivation of critical discernment, for instance with regards to the risks of being exposed to speculative financial systems, or to the issues of maintaining two different values for the currency Faircoin in spite of the cryptocurrency market crash. Besides, when severe conflict erupted, there were no capabilities in place for conflict transformation and mutual learning to occur. And while a number of bold projects were initiated within FC, it appears that the notion of leadership remained mostly conflated with the role of the FC founder, and that the community had neither the structures nor the norms and values that would have enabled leadership to be more equally distributed and acknowledged. It is unsurprising to me, therefore, that no mycelium of radical change-oriented initiatives was allowed to grow in FC.

In the case of DAF, the community was founded on the premise that the collapse of industrial society was underway, and that this reality was widely unacknowledged. From the beginning, cultivating critical discernment with regards to various forms of denial (Bendell, 2018), and to the nefarious influence of harmful ideologies reproduced unconsciously (Bendell, 2021), was thus an important theme within DAF, as exemplified in the methodology of Deep Relating (Carr and Bendell, 2021). This attention was also repeatedly manifested in the community dialogues organised regularly within the network, to take stock of activities taking place and decide on new strategies.

However, likely as a reflection of the dominant culture from which DAF has sprung, critical and difficult conversations were not always welcome. For instance, discussions on whether a large Facebook group dedicated to talking about collapse was indeed helpful and relevant, considering the triggering nature of the topic and the difficulty of engaging in true dialogue over such a tool, were sometimes shut down. And very little common sense-making and restorative discussion occurred on the topic of Covid-19 policies, in spite of the controversy that has occurred in this regard in the realm of digital information and beyond. Besides, as a participant in the D&D circle, I was disappointed by the relatively low number of participants displaying an interest and willingness to engage critically with the topics of anti-racism or systemic oppression in general. Overall, it may not be unfair to say that a culture of “being nice” and “mutual coddling” remained very present in most DAF groups. While this may have fostered a sense of belonging and emotional safety, it likely prevented more collective discernment to emerge, and thus for the constitutive denials of modernity to be more fully confronted through mycelial, change-related initiatives.

With regards to conflict transformation, social learning occurred over time in certain groups I was part of, most notably the D&D circle. As a result, I feel better equipped to engage with conflictual situations. But it was more difficult for me to assess the extent to which this has occurred elsewhere in the community. At the time of writing, there were no formal protocols or guidelines in place within DAF to address conflict, which was probably a sign that much work remained to be done in this regard.

Finally, a culture of collaborating in small teams slowly spread in DAF (Chapter 5), and the community stopped relying on a single leader since DAF Founder Jem Bendell stepped down from his responsibilities in September 2020. These were encouraging signs, signalling the uptake of distributed forms of leadership. As the DAF Core Team was poised to retire from its functions in 2023, for lack of funding, the future will show to what extent this assessment was correct.

In this chapter, I have explained how I have come to consider radical collective change as involving a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives that face the constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality. I have also outlined certain characteristics that I believe are essential for prefigurative communities of critical discernment to exist and cultivate this mycelium – fostering belonging, leaning into conflict, and facilitating emergent forms of leadership. This perspective is predicated on adopting a decolonial stance – and as such, it feels important to point out certain limits of this stance, which I will address in the last section. But first, I will highlight how my work relates to other research efforts.

In her PhD research on decolonial educational spaces, Stephanie Steiner (2022) shares a “potential ingredient list” (p.104) that one can use to create decolonial pedagogies – i.e. emancipatory “cycles of learning, unlearning, relearning, reflection, and action” (ibid.) that aim to further struggles of social and political transformation. Her list brings together various enabling elements of decolonial (un)learning which confirm my own findings, such as fostering trust and vulnerability; leaning into generative conflict; reorienting towards relationships; embracing emergent and collective leadership; and others. It is the only study I am aware of that investigates decolonial (un)learning within informal settings.

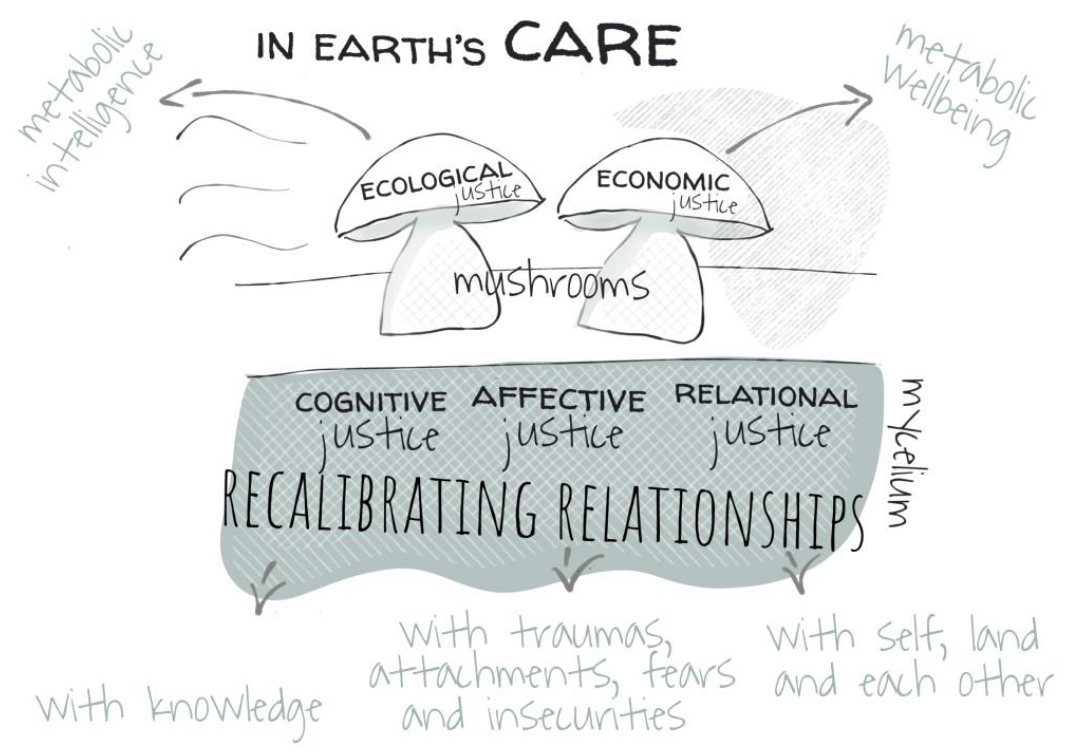

Another metaphor for social change relying on the image of a mycelium has also been put forth by the GTDF collective (Stein, V. Andreotti, et al., 2020).

Figure 12: Cartography: In Earth’s CARE Global Justice and Well-Being Framework. Source: Stein et al, 2020

According to the social cartography in Figure 12, ecological justice (“acting from and towards metabolic health and wellbeing”) and economic justice (“cooperating towards systemic (metabolic) balance”) are only possible if cognitive, affective, and relational justice are taken care of first (Vanessa Andreotti et al., 2018, p. 6). Cognitive justice refers to “nurturing encounters of knowledges and ignorances” – but also includes “recalibrating our relationship with language, meaning and knowledge” (ibid). Affective justice concerns “digesting and composting our traumas, fears, denials and contradictions” (ibid) while disinvesting from harmful modern-colonial desires and addictions. Finally, relational justice is about “relating beyond knowledge, identity and understanding and enacting politics from a space of collective entanglement and radical tenderness” (ibid). In each of these dimensions, the work of recalibrating relationships is essential, and points to relationality as the foundation for new forms of politics and “justice-to-come” (ibid).

The mycological metaphor that I have used in this chapter was not inspired by this cartography – or at least, not consciously. There are similarities between both images, although mine is not centred on issues of justice, while the one by GTDF does not explicitly concern itself with communities as agents of change.

Importantly, my perspective shares with both research projects above a fundamental starting point: that of adopting a relational approach to the topic of social change. In effect, this is the main answer I have found to the research question guiding this chapter. Assessing radical collective change needs to take place beyond modern frameworks of analysis predicated on separation and duality.

In the previous sections of this chapter, I have argued in favour of adopting decolonial approaches as part of prefigurative efforts to bring about generative collective change. However, before closing this chapter, I would like to address recurring criticisms of these approaches, which point to potential limitations. I will focus on those that have the most immediate relevance to this research.

A first area of criticism, according to Stein and colleagues (2020), is that “critiques of coloniality tend to rest on uninterrogated essentialisms about both the West and its ‘others’ (p.2). For example, Vickers (2020) suggests that using notions such as “the West” or “Euro-America” in reference to the history of modern colonialism may reproduce “a vague and divisive system of categorization” (p.5). Similarly, Altschul (2022) and Asher (2013) charge that decolonial theorists, in spite of their stated intentions to deconstruct and transcend the dualist thinking characteristic of modernity, reproduce forms of binary thinking by classifying knowledges and speakers as either representative of dominating or subaltern polities and power structures. Considering the ongoing trends of social polarisation I have referred to above, and the importance of enabling dialogue and containers for critical conversations within prefigurative projects, this argument might disqualify decolonial approaches as overly divisive, if not simplistic.

For Gallien (2020), this reliance on “a monolithic version of ‘the’ West and of ‘modernity’” (p.50) calls for more fine-grained categories of analysis, as well as closer considerations of the power relations that are constitutive of the other epistemological orders and cosmologies that are foregrounded by decolonial theory. On the other hand, Stein and colleagues (2020) argue that strategically mobilising an overarching critique of Western knowledge production may be inevitable for the decolonial critique to be heard, and for it to have the strength to alter the overall impact of colonial power. They also point out that emphasising heterogeneity can be a means of bypassing the difficult work of acknowledging and addressing systemic and historical injustice, for instance when policymakers in settler colonial states neglect to properly consult Indigenous communities in view of implementing certain projects, on the grounds of these communities’ complexity and heterogeneity.

I believe that decolonial critiques provide a powerful lens to examine global historical and social continuities that have shaped the modern world, but that this lens should be fine-tuned to the discontinuities characterising local contexts under consideration.

Another recurring criticism concerns the non-Western knowledge systems that are foregrounded by decolonial theory, as “radically distinct perspectives and positionalities that displace Western rationality as the only framework and possibility of existence, analysis, and thought” (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018, p. 17). Scholars (Browitt, 2014; Vickers, 2020) argue that this leads to romanticising marginalised peoples and their knowledges. For others (Asher, 2013), academics engage with these knowledges without enough consideration for “the complexities of representing the subaltern and what circumscribes their speech and reception” (p.838). Some decolonial scholars have even been accused of adopting an extractive approach with regards to subaltern epistemologies, and to turn them into commodities made available for consumption in the neoliberal academy, in order to accumulate more economic or symbolic capital (Cusicanqui, 2012; Altschul, 2022).

As an aspiring scholar-activist (Chapter 1), I want to be extremely careful in how I engage with other forms of knowledge than those I have been socialised into, as I try to bring about radical collective change. This includes an intention to remain aware of any sense of entitlement to access these knowledge systems, of the risk of instrumentalising them for personal gain, and of failing to pay attention to their context of emergence and the usage of particular stories or practices (Elwood, Andreotti and Stein, 2019). Combining both relational and intellectual rigour appears essential as part of learning to cultivate this discernment (Machado de Oliveira, 2021). It also requires that I inform myself about how cultural appropriation and epistemic extraction have been a violent staple of colonialism throughout history – and that I remain open to criticism if anything I say or do perpetuates these patterns (Ahenakew, 2019). Besides, I am also conscious that the act of romanticising is just as violent and objectifying as that of demonising – which encourages me to adopt an attitude both “deeply respectful” and “highly sceptical” of any worldviews, be they my own or others’ (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.206).

Scholars have also pointed out that aspects of non-Western worldviews could even be appropriated, in a particularly distorted fashion, to justify authoritarian forms of politics. For instance, Gosselin and gé Bartoli (2022b) foresee the risk that viewing the planet as an endangered metabolism – “Gaia” – could lead it to be framed as an “overbearing and tutelary figure” serving as a pretext for new totalitarian forms of planetary governance, based on generic and universal norms, to be imposed upon all human and non-human beings. Needless to say, this would run very much contrary to the emancipatory and pluriversal ethos of decolonial approaches. Ecofascism scholars (Biehl and Staudenmaier, 1996; Dubiau, 2022) have also highlighted how theories concerning humanity’s place as part of a moral or spiritual “natural order” are fundamental to reactionary, anti-modern politics from the past and the present (such as the völkisch movement in early 20th century Germany, or the Nouvelle Droite in France currently).

These warnings are essential to take into consideration whenever promoting knowledge systems that do not reproduce the modern ontology separating humans from the other-than-human world. However, I still believe this modern ontology is even more harmful and needs to be challenged, for other possibilities to emerge.

A third type of criticism views decolonial theory as too abstract and disconnected from social movements and political struggles. A prominent decolonial scholar admits as much:

The lack of direct relation with struggles and concrete situations, with certain exceptions – and the academic jargon that characterises most text – remains one of the most accurate criticisms of [the decolonial] perspective. (Escobar, 2014, pp. 42–43)34

This critique is voiced strongly by Cusicanqui (2012), who charges that decolonial scholars have developed a “logocentric” conceptual apparatus that is disconnected from “insurgent social forces” and yet which “neutralize decolonization” and “capture the energy and availability of indigenous intellectuals” by “depriv[ing] them of their roots and their dialogues with the mobilized masses” (p.98-103). She concludes that “there can be no discourse of decolonization, no theory of decolonization, without a decolonizing practice” (p.100). From a slightly different angle, Tuck and Yang (2012) argue that “decolonization is not a metaphor,” and that the enterprise of decolonising the mind can be used as a “settler move to innocence” and thus “stand in for the more uncomfortable task of relinquishing stolen land” to Indigenous peoples (p.19).

As I discuss in the D&D Circle case study (Annex 5.3), while I agree that “a more radical decolonizing politics center[s] material life and colonial extractions, including the appropriations of land and destructions of environments and livelihoods” (Murray, 2020, p. 324), I do not see this as antithetical with the intention to “interrupt modern/colonial patterns of knowing, desiring, and being” (Stein et al., 2020, p. 5).

It is also important to remember that the question of praxis is considered central by many decolonial scholars. Indeed, according to Gallien (2020, p. 41), “Decolonial thinkers habitually describe their interventions as forms of praxi-theory, that is theory leading to action and vice versa. Contrary to the belief in a-perspectival and universal truth in scientific discourse, decoloniality presupposes that knowledge is always the result of an embodiment and commitment.” For instance, Maldonado-Torres (2016) describes decoloniality as “giving oneself to and joining the struggles with the damnés35.... decoloniality is rooted in practical and metaphysical revolt” (p.30). And Walsh views this praxis as “the continuous work to plant and grow an otherwise despite and in the borders, margins, and cracks of the modern/colonial/-capitalist/heteropatriarchal order” (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018, p. 101). Jivraj, Bakshi and Posocco (2020) list several recent political movements and social projects that have been initiated as practical embodiments of decolonial analyses and alternatives, including student-led activist initiatives or the repatriation of museum artefacts to Global South countries.

Thus, while it is true that decolonial theory may sometimes be problematic to articulate in lay terms, I am confident that its praxis holds much potential for the enactment of radical collective change, both on the onto-epistemic and on the political level. I agree with Monticelli (2021) on the necessity for prefigurative efforts to include a decolonial approach, in order for them to bring ontological and epistemological forms of change that may complement the action of more traditional parties and protest movements focused on the social transformation of power relations.

Finally, one last area of criticism I will touch on concerns certain prominent decolonial scholars, which are presented as a small circle of “gurus” (Cusicanqui, 2012, p. 102) having accrued power and influence through prestigious academic positions, and driven by a logic of conversion: “decoloniality strives to force a quasi-religious transformation and to create a world converted to speak from the side of subalternity” (Altschul, 2022, p. 8). These authors are depicted as a hierarchy of fundamentalist “high priests,” demanding “orthodox belief and practice,” and having arrogated the authority to judge whether one’s “conversion to decoloniality” was successful or not (ibid).

Nonetheless, several decolonial scholars have clearly acknowledged their own inevitable complicity in harm, and implication in affective and relational economies of worth that are integral to modernity-coloniality. For Machado de Oliveira (2021, p.238), “no one has the answers to our current predicament” and “no one is ever off the hook.” Grosfoguel admits that “we are all affected by modernity-coloniality. While some of us are confronting the challenge of decolonising ourselves, no one, myself included, can claim to have succeeded”36 (Grosfoguel and Andrade, 2013, p. 46).

It is true that the decolonial perspective’s attachment to epistemic justice aims at “dismantling the hegemonic universality and centrality of Western Eurocentric knowledge, or putting Western knowledge in its place” (Steiner, 2022, p. 106). However, this does not imply the aim to “convert” as many “believers” as possible to other, equally hegemonic, forms of knowledge. Recognising that all knowledge systems are partial and situated, Santos (2018) calls for the cultivation of an “ecology of knowledges”: instead of seeking to replace Western knowledge with non-Western knowledges, which would perpetuate the universalist tendencies at the heart of modernity-coloniality, all should be allowed to coexist without one subalternising the others.

As for the participants in the GTDF collective (Stein, V. Andreotti, et al., 2020), they are conscious that “decolonial critiques have become a valuable currency within the intellectual, affective, relational, and material economies of mainstream Western educational institutions” (p.44), and they suggest avoiding unhelpful attachments to any orthodoxy, and cultivating an attitude based on “suspending our desire for universal or prescriptive solutions and... instead attending soberly to what is currently working, and what is not” (p.62). Instead of seeking to universalise any particular approach to social change or decolonisation, they invite collective reflection: “How can we move together differently toward a future that is undefined, without arrogance, self-righteousness, dogmatism, and perfectionism?” (p.63)

For me, the decolonial perspective calls for humility and self-reflexivity, not pontification from a higher moral ground. It combines a radical depth of critique with an awareness of the limits of any forms of knowledge. I view it as particularly suited to our times, considering the extreme difficulty of knowing what may be the most generative ways of attempting to bring about radical collective change. However, I do not advocate it as the “one true way” of achieving generative change. How should I know?

In the final chapter of this thesis, I conclude on my main research findings and their relevance to my research question.