Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

If I am not in the world simply to adapt to it, but rather transform it,

and if it is not possible to change the world without a certain dream or vision for it,

I must make use of every possibility there is not only to speak about my utopia,

but also to engage in practices consistent with it.

- Paulo Freire (2004, p. 7)

This is a qualitative research project, which I have carried out from a pragmatic perspective, and with a constructivist epistemology.

An important characteristic of pragmatism as a philosophy is that claims to knowledge are made as a result of engaging with the world, and that “truth is found in what works” (McCaslin, 2008, p. 672). Truth is thus situated and relative, and “what works” or not in practice must be tested in practice through experimentation and reflection, and involve a collectively constructed experience - a perspective that corresponds well with my first-person and second-person Action Research inquiry methodology, and with the participatory ethos I have embraced (see below). Ultimately, for the pragmatist, “truth is co-created by way of intersubjective relationships” (ibid, p.673).

As my research unfolded, my stance took on an increasingly “critical pragmatic” angle, in that I have come to pay closer attention to social processes of inequality reproduction, such as stigmatisation, othering, or marginalisation, and grew more comfortable in taking on an activist role of citizen-scholar (Vannini, 2008).

I have adopted a constructivist epistemology, particularly throughout my case study analyses. The main reason for this is that one of the central concepts in my research, the notion of radical collective change, is one whose definition may completely vary from one person to the next, and in keeping with the aspirations stated above, I did not wish to impose my own (evolving) understanding thereof within the various research activities I convened or took part in (see below). Constructivism considers that “there exist multiple, socially constructed realities ungoverned by natural laws, causal or otherwise” (Guba and Lincoln, 1989, p. 86), devised by individuals as they make sense of their experience, and more or less commonly assented to by others. Thus, from a constructivist perspective, what counts as desirable change may differ from person to person, and be redefined continually in the light of new experience. This process is necessarily a function of the values embraced by the person. Therefore, from this perspective, aspirations for social change should remain open to contestation, conflict, and negotiation; diverse voices should be brought into dialogue; and attention should be brought to issues of power and social stratification in the course of these discussions.

The guiding research methodology for this thesis is Action Research (AR). AR enables me to link together different localised approaches to the data under a consistent and coherent framework for analysis. In this chapter I will first establish the principles of AR and its relevance to the thesis, before detailing how it was used as an overarching approach to the specific data collection for each of the areas of study.

AR is an approach that pays attention equally to various forms of knowledge (or learning), and to action. I see this methodology as relevant to my research precisely because I want to explore the interface of learning and action.

Indeed, AR is an approach to inquiry based on experimental action: it is about generating knowledge (research), while at the same time supporting positive change (action):

Action research is a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities. (Reason and Bradbury, 2008, p. 4)

Fundamentally, AR is a cyclical process of trial and error, where people observe existing practices, reflect on them, then find ways to improve them.

AR researchers (e.g. Heron and Reason, 2008) point out that doing this meaningfully requires making sense of reality — including social systems — in a holistic way: not simply through an analytical process taking place after an event has been observed, but via a relational and experiential process taking place as things are happening. Burns (2007, p. 3) emphasises that AR is a process of coming to know, by using all one’s faculties and senses. This is another important factor for me in choosing AR as a methodology, as the learning I am interested in goes beyond the cognitive field – I am especially keen to explore its relational dimensions (Bradbury et al., 2019), as I will explain in the next section.

In the words of Greenwood and Levin (1998, p. 93), AR is

a cogeneration process through which professional researchers and interested members of a local organization, community or specially created organization collaborate to research, understand and resolve problems of mutual interest.

Because online networks are fundamentally participatory, this focus on participation is another reason for me to choose AR. As Reason and Bradbury (2008, p. 8) point out,

In AR, ‘participation’ is more than a technique, epistemological principle, or political tenet. An attitude of inquiry includes developing an understanding that we are embodied beings part of a social and ecological order, and radically interconnected with all other beings.

Therefore, the practice of AR is rooted in the realisation that we are not bounded individuals experiencing the world in isolation: we are all interconnected, participants in a whole, “part-of and not apart-from.” (Reason and Bradbury, 2008, p. 8). AR is fundamentally about transcending the idea that each of us is a separate, disconnected entity. This “story of separation,” a central component of the modern-colonial world, is largely to blame for the global social and ecological predicament – as I will argue in Chapter 6.

Practitioners view AR as a way of carrying out research and acting in the world that has an explicitly egalitarian and democratic ethos, which resonates with the socially just aims of the networks involved in this study:

AR is a social process in which professional knowledge, local knowledge, process skills, and democratic values are the basis for co-created knowledge and social change. (Greenwood and Levin, 1998, p. 93)

The primary purpose of action research is …. to liberate the human body, mind and spirit in the search for a better, freer world. (Reason and Bradbury, 2008, p. 5)

Therefore, a direct link can often be observed between AR and social change: indeed, “AR explicitly seems to disrupt existing power relations for the purpose of democratising society.” (Greenwood and Levin, 1998, p.88)

AR is thus a particularly relevant approach as it is fundamentally sympathetic to the forms for generating social and political change through democratic principles.

AR is not a predetermined process, ruled by rigid and immutable guidelines. Instead, it is an emergent process, in the sense that it changes and develops as the people engaged in the research deepen their understanding of what they are studying, and become better at it both individually and collectively (Reason and Bradbury, 2008, p.4). This aspects makes AR particularly relevant to the study of emergent, organically developing networks.

In order to be useful and relevant (and therefore, create understanding and change), an AR research process must remain flexible, and adapt to fluid settings. Part of this flexibility comes from relying on repeated cycles of inquiry. It is therefore a process that alternates action and critical reflection. I have tried to embed this reflexive cycle into all aspects of this research.

In order to answer my research question, I have initiated AR projects within two distinct online networks and communities (see below). Simultaneously, I have also strived to be mindful of my own learning, changes, and assumptions, as I participated in these research efforts with others. Therefore, I have applied AR in two different ways: second-person, and first-action.

Second-person AR refers to

action research approaches that involve two or more people inquiring together about questions of mutual concern. In this form of research, the researchers and the research subjects are one and the same. Co-inquirers work together to identify and formulate inquiry questions, to determine the ways in which information will be gathered, to make sense of it and to act on their conclusions. Groups are small enough to have some significant relationship with each other, traditionally meeting face-to-face, although use is increasingly being made of online and virtual inquiry groups. (Coleman, 2014, p. 698)

It is a form of AR that centres the commitments to collaboration, mutual respect, and collective emancipation that I have introduced above, and is strongly informed by “the idea of research with people rather than on them” (ibid). An important reason for doing so is that it constitutes a form of resistance against the tendency for academic elites to claim knowledge of others, and thus exercise a right to speak and categorise their everyday reality on their behalf, thus perpetuating unjust power structures. On the contrary, “since the act of recognizing and naming one’s own experience in collaboration with others is an affirmation of individuality and autonomy, this in turn can contribute to the political emancipation of those involved” (ibid, p.699).

Researchers have long pointed out the many practical and ethical quandaries that afflict participatory research projects, and place severe constraints to the possibility of achieving such equality, or emancipatory outcomes (e.g. Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995; Bergold and Thomas, 2012; Beebeejaun et al., 2014). In the case of this research, for example, obvious obstacles emerged from its very nature as an academic endeavour, which imposes a particular time frame, and requires that a final research output be authored by me, the PhD researcher, alone.

I have tried to remain aware of these limitations and to reduce their impact as much as possible. This has led me to rely on ways to co-produce knowledge in forms more accessible to non-academic participants, such as videos and storytelling (Little and Froggett, 2010). And in both communities, I have strived to leave as much space as possible, given the constraints above, for participants to flexibly engage in the research process, at the depth they felt most comfortable with – from a role of informer or consultant to that of co-researcher (Arnstein, 1969; Hart, 1992) – while being transparent with them as regards the conditions of our collaboration stemming from its academic context. Such conditions, along with other critical information, were presented in the Participant Information Sheets that I prepared for each network (Annex 3.1), and which I asked every participant to read and consent to before becoming involved.

Finally, in keeping with the emergent and participatory aspects of this research, I refrained from planning the whole research in more detail from the outset. Instead, the participants who wished to be more deeply engaged in the project co-designed the research process iteratively with me, following the experiential learning cycle referred to above.

In the next sections, I present in more detail the ways in which I have brought second-person AR into the groups with whom I carried out the participatory aspects of this research. But first, I will say a few words about another form of AR I have put into practice.

I combined Second-Person AR with First-Person AR, which is “an approach undertaken by researchers as an inquiry into their own actions, giving conscious attention to their intentions, strategies and behaviour and the effects of their action on themselves and their situation” (Adams, 2014).

An important way in which I have been undertaking this reflective and self-critical process – all the way to the writing of this thesis – is by holding a research journal, in which I have been collecting thick descriptions of my personal and interpersonal experience of this research. I have been regularly returning to it in order to study the evolution of my thinking and reflect on my assumptions. Besides, I have also made sure to explicitly link these descriptions to my conversations, data collection and analyses, literature study, and other key processes of my research, thus creating layered accounts (Charmaz, 1988). This multi-layered text has helped me keep track of the simultaneous unfolding of my data collection and analysis processes, and to reveal how this research has been as much a “source of questions and comparisons” as anything approaching a “measure of truth” (Ellis, Adams and Bochner, 2011).

This journal has been particularly useful to my writing the reflections presented in Chapter 6, in which I use excerpts to discuss my evolving ideas of what may constitute necessary forms of radical collective changes, as a result of the social learning I have been experiencing through this research. It has also facilitated the reflective process carried out with my co-researcher Wendy Freeman about the work of our research team in DAF (Annexes 5.5 and 5.6).

I will now provide more details about my research process for each of the two online communities in which and with whom it has taken place.

The research process in FairCoop (FC) unfolded between June 2020 and October 2021. The following is a summary of this process, which is presented in more detail in Annex 3.2.

My original intention was to invite participants in FC projects to form a participatory research group, which would explore the kinds of social learning taking place within FC. But among the participants I contacted, no one had any motivation to do so. Several of them said the community was “dormant” or that it had “failed,” and that it was deeply divided as a result of intractable conflict.

Consequently, I shifted my approach to a diagnostic/evaluation stance. Out of these first conversations, four Research Questions (RQ) emerged which seemed to speak to the interests of the participants I interviewed while corresponding with the overall intention underlying my PhD research:

I decided that RQ #1 and #3, being more straightforward, could be studied by conducting semi-structured interviews followed by a thematic analysis. RQ #2 and #4, however, called for a more rigorous evaluation methodology, which would give equal weight to a variety of perspectives, and encourage participants to learn from one another.

However, it rapidly emerged that most interviewees were unwilling to engage in any evaluation otherwise than through individual, private conversations with me, for lack of time, and due to the lasting impacts of deep-seated conflict. I thus decided to base the evaluation process, needed to answer Research Questions #2 and #4, on the use of Convergent Interviewing.

CI is a flexible data collection process, based on an in-depth interview procedure characterised by a structured process and initially-unstructured content (Dick, 2017). CI is also emergent and data-driven, has a cyclic nature, makes use of a dialectic process, and can be used effectively in community change programs as part of a diagnosis or evaluation project (Dick, 2002, 2014, 2017).

Overall, the CI process can be outlined as follows (Driedger et al., 2006; Jepsen and Rodwell, 2008; Dick, 2017):

- Entry and contracting;

- Preparing a maximum-diversity sample;

- Carrying out initially open-ended interviews, from which an evaluation develops gradually and inductively;

- By comparing interview results, developing probe questions to deepen one’s understanding of the emerging theory.

CI is based on a constant comparative reflexive process (Driedger et al., 2006). The cyclic nature of this process “allows the refinement of both questions and answers, and even the method, over a series of interviews or successive approximations” (Riege and Nair, 2004, p. 75). This builds rigour in the continuous refinement of the research content and process, while providing flexibility, which is useful in an Action Research context.

In the early stages of my interviewing process, I invited several of my FC contacts to form a group of co-researchers with me. However, it appeared that this was not possible for any of them at the time. Therefore, I pursued the research process on my own.

In order to form a sample, I asked my initial contacts to recommend other participants in the FC network who would have different backgrounds and points of view from them, while still being representative of the network. I then contacted the persons they recommended. When these responded positively to my request (which was the case about 50% of the time), I had an open-ended discussion with them, and then asked them to recommend another person I could speak to, with the same criteria as previously. In this way, a modified snowball sample of 15 participants emerged.

Interviewees were all persons who were deeply involved in FC as a project, ranging from 1.5 to over 4 years of participation (average: 3 years) at the time of first interview. They included persons identifying with either (or none) of two broad and opposing factions that seem to have formed within FC, and hailed from 8 different countries. I deemed this sample diverse enough for the purposes of understanding the history and dynamics at play within FC.

Ahead of interviewing anyone, I asked them to express their consent to take part in this research, by sending me an electronic message containing the copy and pasted paragraph titled “Consent email” from the online information sheet (see Annex 3.2). This was usually achieved by sending prospective interviewees an instant message containing this text, and asking them to reply to this message saying “I agree.” For those with whom I communicated in Spanish, I translated this paragraph into Spanish.

All my initial communications with FC participants happened over the instant messaging software Telegram. 6 interviewees agreed to be interviewed over video-conference calls, and 9 via private Telegram text and recorded voice messages. 11 discussions took place in English, and 4 in Spanish.

In the case of video calls, taking place over videoconference, I took extensive notes during the interview. In the case of Telegram voice messages, I transcribed the messages I received. I translated into English notes and text messages that were in Spanish to facilitate the analytical process, and analysed all text using the thematic analysis software Quirkos.

Interviews happening over video calls were clearly bounded in time, and took one to two hours. Interviews carried out over instant text messages or voice messages were more continuous, as they allowed the interviewee to respond whenever they had time. This enabled several “interviews” to be taking place simultaneously, which made the process more dynamic – as I was, in effect, able to rapidly test for agreement or disagreement when a new issue was raised by someone.

I regularly summarised my understanding of what interviewees were sharing with me and submitted these summaries to them, to confirm I understood them correctly.

In order to explore the two closely related research questions (RQ #2 and #4) that called for the use of CI, I began by asking the interviewees to tell me more about their experience of FC. In particular, I asked them what they considered had been the main challenges that FC had faced or was facing as a project, as a “general probe” question (Dick, 2017, p.7).

By comparing my notes from each interview to my corpus of previous interviews, I then gradually began building an emergent theory about the general categories of challenges that appeared to have been present in FC (ibid, p.13). In effect, I carried out an inductive thematic analysis, building on the method of Template Analysis (TA), as presented by King (2004, 2012) and Brooks and colleagues (2015).

Through this process, by updating the emerging template iteratively after each interview, I gradually came to build the following template of themes, corresponding to organisational issues experienced in FC by interviewees:

- Objectives and strategy

- Ways of doing

- Ways of being

For each sub-theme, I devised probe questions testing for agreement on the relevance of each issue identified. In a spreadsheet, I kept track of the agreements, disagreements, or “no opinion” voiced by interviewees for each issue.

In the Case Report (see next section), I included issues that appeared significant to at least three interviewees, and attempted to systematically point out the degree of agreement or disagreement for each issue.

Answers to the research questions that weren’t directly connected to the evaluation process (i.e. RQ #1 and #3) were also included in the convergent interviewing process, although more lightly. This was due to the broad agreement on the history or trajectory of FC as a project (RQ #1), and to similar replies to the questions that had to do with the positive and negative outcomes that interviewees voiced with regards to their participation in FC (RQ #3). Nonetheless, particularly concerning the latter, interesting answers from one person would help me develop probe questions to ask other people.

In the case of RQ #1, I triangulated the information I received from interviewees with several media reports and studies on FC.

In order to test my understanding of what the interviewees had shared with me, and invite constructive feedback and criticism, I decided to summarise my findings into a Case Report.

This was an iterative process which took place from January 31 to October 1, 2021. Over this period of time, I shared three successive draft versions of this report with interviewees, before sharing the final version on October 1.

The drafts were shared using the online platform OnlyOffice, and could only be read by viewers receiving the secret URLs leading to them. The final report was shared as a PDF.

I wrote the drafts and the final report in English, and translated each of these versions entirely into Spanish to share them with the interviewees with whom I was interacting in this language.

The 40-page report presented the study and the methodology, and answers that had emerged for me to the four Research Questions – first as an executive summary, then in more detail. I quoted at length from the interviewees, whom I anonymised.

I used the drafts to collect feedback, by inviting study participants to comment directly and anonymously on the online documents in the language of their choice. To overcome the language barrier, I translated all comments posted from English to Spanish or vice-versa, and posted the translated comment at the appropriate location on the other version of the document.

This methodology allowed me to receive many useful comments, and to nuance several parts of the text. These draft reports also enabled me to query interviewees’ wishes and feelings with regards to the publication of the final report, in order to cause as little harm as possible. I viewed this as necessary, considering the community’s conflictual history, and the negative opinions voiced by most interviewees about the FC founder.

Eventually, following a deliberative process, it appeared acceptable to publish the final report while anonymising the community and its founder – and to inform study participants that this information would be revealed in the present thesis. I published the report on October 1, 2021, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

I will now turn to the second online community in which this research took place.

When I decided to undertake part of my research within the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF), in January 2020, I had already been deeply involved in this network for nearly a year, as part of its core team. This made my position as a researcher very different from the one I had with respect to FairCoop, in which I was merely an external sympathiser. In DAF, I had much easier access to a great diversity of participants.

Besides, while FC was at a standstill, DAF was in full expansion. This allowed me to more directly address the fundamental questions that had moved me to undertake this PhD research in the first place. In particular, I was most curious to explore the learning processes taking place within online networks, and to consider the extent to which they enable participants to take action collectively on social issues of common concern.

Originally, I articulated (to myself and others) this twin concern for learning and action by stating that I wanted to:

- understand to what extent a network enables its participants to learn about the social issues they care most about, and to act on those issues;

- find out if participants consider these functions to be important to them (i.e. whether these functions of learning and acting are among the main reasons for their joining this network in the first place);

- consider whether they find the network wholly satisfactory in these terms;

- and if it isn’t, how these functions could be improved.

I was unsure what theoretical framework might allow me to bring equal attention to learning and action within networks and online communities. I found a way forward in discovering the social learning theory developed by Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayner (Wenger, 1998, 2009; Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015), and the practical frameworks they have put forth to assess and foster social learning within – offline or online – communities of practice (Wenger, McDermott and Snyder, 2002; Wenger, White and Smith, 2009), and social learning spaces (Wenger, Trayner and De Laat, 2011; Wenger-Trayner et al., 2019; Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2020).

In particular, the social learning evaluation framework developed by E. and B. Wenger-Trayner (2020), and which is based on iterative cycles of action and reflection, is very AR-compatible. It empowers participants to decide what counts as valuable learning; it is open to change and evolution, which is useful within an iterative (experiential) research project; and it is meant to bring a direct improvement to the situation researched, which is also the aim of Action Research as a whole. More broadly, the Wenger-Trayner social learning theory is a good fit with my onto-epistemological perspective. Indeed, it is built from a pragmatic perspective, assuming that “what counts as value is what achieves a desirable end” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2020, p.52), and that because the world is in a state of constant change, there can be no “timeless list of what is good or bad, or of ends to be achieved or avoided for their own sake” but rather, criteria of value judgments should be “legitimate objects of inquiry” (ibid, p.52-53). This theory also accounts for how learning and value-creation are embedded in “the complexities of identity, community, and society” and so this perspective “embraces the multiple perspectives and interpretations created by different human experiences and social contexts” (ibid, p.53).

I will now present a brief summary of these key theoretical components, which became the key building blocks for the research I carried out in DAF.

The Wenger-Trayner learning theory is about “thinking about learning in its social dimensions” instead of learning as a biological, cognitive, psychological, or historical process: “It is a perspective that locates learning, not in the head or outside it, but in the relationship between the person and the world, which for human beings is a social person in a social world” (Wenger, 2010, p. 179). Learning can be viewed as the production of social structure, involving dynamic processes of personal participation in social activities such as conversations or reflections, intertwined with the production of artefacts (reification) such as concepts, stories, methods or documents. Over time, these processes create a social history of learning that combines individual and collective aspects, giving rise to communities of practice - that is,

groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn to do it better as they interact regularly (E. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015a, p. 2).

A community of practice is thus determined by a membership, comprised of people who build relationships in the course of regular interactions; a practice, made of “a shared repertoire of resources: experiences, stories, tools, ways of addressing recurring problems” (ibid); and a shared domain of interest, to whom members are committed and with regards to which they develop a shared competence distinguishing them from other people.

Communities of practice show that learning is also the production of identity: by engaging with the shared repertoire of resources within various communities of practice, in all spheres of one’s life, one is recognised by other members of these communities as more or less competent with respect to the community’s domain, which becomes a crucial aspect of one’s identity. “Learning in a community of practice is a claim to competence” (E. Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015b, p. 14): members of a community are ceaselessly called to redefine their regime of competence whenever new members join them, while the experience of newcomers is simultaneously shaped by this regime.

Another important aspect of communities of practice is that they tend to form part of complex and political landscapes of practice, involving other communities, which are brought together by a common body of knowledge (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015). Learning can be seen as taking place not only within each community of practice, but also in relation to this broader landscape. In this way, much learning may happen at the boundaries between communities, as different practices and perspectives come into contact and friction, leading to conflict or mutual exchanges and to increased knowledgeability in participants about the whole landscape (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2016).

But how to cultivate the social learning capability of these social systems? According to Wenger (2009, 2010), this requires special attention to issues of governance – that is, to the balance between an emphasis on stewardship versus emergence, with regards to directions and priorities for learning; and to issues of power, which require a fruitful interplay between vertical and horizontal accountability processes. Finally, cultivating social learning capability is also a matter of personal responsibility: the ethics of how every participant invest their identity as they travel through the landscape – their learning citizenship – is another critical side of the social discipline of learning.

I will pay special attention to these aspects and others in Chapter 5, as I consider the factors that appear to be most supportive of social learning processes within DAF.

While the early stages of the theory (Wenger, 1998) already conceptualise personal and collective action as fundamental to these dynamics of learning (through the emphasis on practice), the link between action and learning is particularly obvious in latest developments. Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayner (2020) introduce social learning spaces as referring to a particular experience of mutual engagement taking place among people in pursuit of learning to make a difference – be it in their inner worlds, in their personal lives, or in the world at large.

Such spaces are not characterised by their geographical location or their physicality, but structured by social relationships: a conversation between two strangers can be a social learning space, and so can a series of interactions within a team confronted to a novel problem. Social interactions and relationships in those spaces are primarily “structured by a desire to push a joint inquiry together” – they bring about “mutual engagement at the edge of participants’ knowing” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner 2020, p.13). Fundamentally, in social learning spaces such as those that online networks may provide, participants...

- care to make a difference: their participation is not perfunctory or compliant, but driven by a need to get better at making that difference, whatever it is – from refining an idea to perfecting a practice or creating political change;

- engage their uncertainty: they participate from a place where their knowledge of how to make that difference tapers off, whether this knowing is descriptive or embodied, instead of a place of certainty;

- pay attention to the responses they receive to the engagement of their uncertainty – including personal reactions and emotions in themselves and others, questions and comments, critiques, and beyond, observations on what seems to be working or not in practice.

Social learning spaces create value for participants to the extent that the latter view engaging uncertainty and paying attention as contributing to their ability to make a difference they care to make (and this value can be positive, negative, or null). The human experience of agency and meaningfulness is thus at the heart of this learning theory.

Value can be created within and across eight different value-creation cycles (Immediate, Potential, Applied, Realised, Enabling, Strategic, Orienting, and Transformative), in a non-linear and unpredictable fashion. Annex 3.3 provides more details about value-creation in social learning spaces, and on how to evaluate it.

I will now explain how I have been using this theoretical framework within DAF.

As I pointed out at the beginning of this section, my primary concern in starting to investigate social learning processes within DAF had to do with understanding the interplay between learning (which I conceptualised as a largely cognitive process) and action (which I viewed as “doing things in the world”).

However, the Wenger-Trayner social learning theory enabled me to consider learning and action as one and the same thing: any new insight, skill, inspiration, action, or personal transformation can be viewed as entangled within a ceaseless flow of social becoming, fostered by our participation in various communities of practice and social learning spaces, and the various modes of identification (Wenger, 2010, pp. 4–5) through which we negotiate our participation in landscapes of practice.

This evolving understanding, and the conversations that occurred as a result with my co-researcher Wendy Freeman, led to a gradual evolution of the research questions that I/we investigated.

The main research question we aimed to answer can be expressed as follows:

To what extent can social learning (and unlearning) taking place in DAF be considered relevant, in terms of the radical collective change required to face our global predicament?

This question was first broken down into the following sub-questions:

1. Subjects and actors of learning:

2. Circumstances and social learning capability:

3. Impacts and results:

Gradually, these questions evolved into the following:

If radical collective change (i.e. change as (un)learning that seems relevant, given the global predicament) is happening in DAF, then...

However, it soon became clear that it was very difficult to assess whether any of the social learning taking place in DAF could be categorised as “radical collective change,” and who was taking part in these changes – if only because it would have required placing more emphasis on the research team’s perspective rather than that of regular participants, which felt contrary to the ethos of the Wenger-Trayner evaluation framework. Therefore, I decided to dedicate a separate chapter of this thesis to my own evolving idea of radical collective change (Chapter 6).

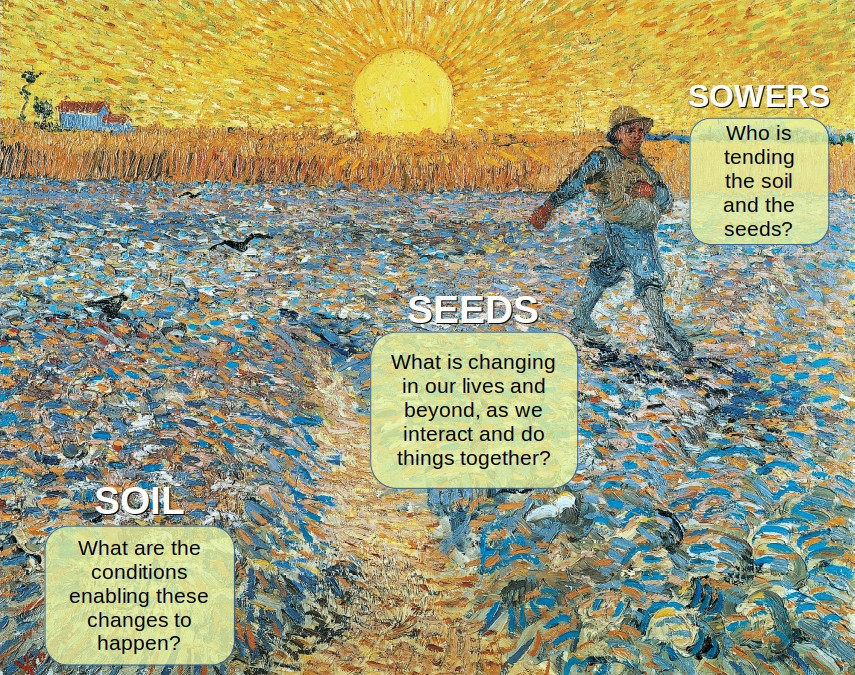

Besides, the relative complexity of the Wenger-Trayner social learning theory and evaluation framework did not seem very conducive to presenting results in a way accessible to non-academics – which is one of the objectives of this research project. Consequently, I decided to use a gardening metaphor in order to structure, within Chapter 5, the presentation of the results from these evaluation processes, and to focus on answering the following questions:

- What are the main “seeds of change” that are being cultivated within DAF social learning spaces? This refers to forms of social learning that appear most relevant to DAF participants, in view of the global predicament. These were mostly found within the “Potential,” “Realised” and “Transformative” value-creation cycles in the Wenger-Trayner framework.

- What are the conditions – or the “soil” - enabling these changes to happen, or preventing them from happening? This refers to the social and material conditions that may help these seeds to grow. These appeared most clearly within the “Immediate” and “Enabling” value-creation cycles. This question also enables me to examine various dimensions of a social system’s learning capability.

- Who are the “sowers” helping to nurture the soil and to sow the seeds, and what forms of leadership do they enact in doing so? This brings the attention to the persons who enact the clearest forms of leadership in creating the conditions for social learning to deepen, within a given learning space and beyond. Their influence and action can most easily be spotted within the “Applied,” “Strategic,” and “Orienting” value-creation cycles, which reveal important aspects of learning citizenship.

Figure 3: Seeds, Soil, and Sowers: Cycles of value-creation. Based on Vincent Van Gogh, "The Sower at Sunset" - Arles, June 1888. Image source: Wikipedia

Importantly, just like the painting in Figure 3, these three categories are impressionistic: it is not always possible to neatly categorise value creation as constituting “seeds,” “the soil,” or the action of a “sower.” It can be all of those at once.

This is largely because, as noted by other researchers making use of this value-creation framework (e.g. Bertram et al., 2014; Bertram, Culver and Gilbert, 2017), it can be challenging to assign a particular comment or activity to one value-creation cycle or to another. For example, a remark stating that one has gained new understanding may be categorised as a sign of Potential, Realised, or even Transformative value-creation.

Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2020, p.123) acknowledge the difficulty:

Social learning does not necessarily involve distinct phases for each cycle. More than one cycle may be involved in any given activity. The creation of value for different cycles may be intertwined and at times indistinguishable.

Nonetheless, in line with the model’s pragmatist perspective, they argue (ibid.) that

the distinctions are useful theoretically as a more refined model for social learning processes viewed as value creation. In practice the distinction is useful for being more intentional about improving learning capability at each value cycle.

Therefore, my understanding is that while each cycle can be generally characterised by certain dimensions of positive or negative value that it tends to create, and by certain ways of producing this value (ibid, p.76), there is no “cut-and-dried” list of criteria for assigning part of a given story to a certain cycle, and that this categorisation largely rests on the value detective’s understanding of this part of the story within the wider context of the entire story, and of the speaker’s stated aspirations. I discuss these issues more at length in Annex 3.3.

For this reason, I view the soil, the seeds, and the sowers as relationally and theoretically entangled with one another. I found these images formed a useful heuristics, as a threefold set of perspectives from which to tell stories about the social learning that has unfolded in DAF.

I will now present an overview of the evaluation processes carried out within DAF using the theory and framework introduced above.

This action research project in DAF began in January 2020. Members of the DAF Core Team, including myself, collaborated with DAF volunteers to create a survey that would be disseminated across the network: the DAF 2020 User Survey. This survey had the twin objective of assessing the usefulness of DAF platforms, and the learning and changes taking place for participants thanks to these platforms. Please refer to Cavé (2022b) for an in-depth analysis of the survey results.

There were 168 survey respondents. In early April 2020, using simple random sampling, I selected 10 of those who had indicated in their response that they would be willing to be contacted by a member of the research team. I reached out to each of them to arrange for one-hour interviews. These interviews allowed me to start gathering contextual narratives, and the outlines of value-creation stories. See Annex 3.3 for details on this interview and analysis process.

This study unfolded over two different time periods:

- From January 2020 to September 2020: I was the only researcher involved.

- From September 2020 to April 2022: I formed a research team with DAF volunteer Wendy Freeman.

From early 2020, I began discussing my research intentions with various DAF volunteers and core team members. While it elicited some interest, no one seemed able to commit to a time-consuming process as co-researchers. In September 2020, I was contacted by Wendy Freeman. We had met through our participation in the DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle, and she had a special interest in social and transformative learning, on which she had written her Masters’ dissertation (Freeman, 2016). We decided to form a research team.

I shared with Wendy the content of the interviews I had carried out already, for those interviewees who agreed to this. Some of them asked me to keep certain details confidential.

Wendy and I decided to meet every second week over videoconference to reflect on our research and agree on next steps.

A detailed account of our work, including the activities we launched, and a comprehensive evaluation of the social learning that occurred through the action of the research team, can be found in Annex 5.5. Here, I will only provide a broad overview of our activities.

On the basis of the emerging indicators and value-creation stories that I had begun to assemble, the research team (RT) agreed on the DAF social learning spaces that appeared most interesting to investigate. One of us would contact a person, share the participant research sheet with them, and arrange for an interview. We discussed beforehand any particular questions we wanted to ask the person.

Following the interview, one of us created the transcript. I then analysed the transcript using the method presented in Annex 3.3, and shared my reflections with Wendy. We discussed any new indicators and emerging information, to decide on our next steps. We occasionally asked the same interviewee if they agreed to join a second interview, a few months later, to see how their participation and experience may have evolved.

In this way, 44 interviews were initiated by the research team, with 36 individuals. Two of these interviews were carried out by the two of us with one another. In this way, we co-created 28 value-creation stories together with DAF participants. Interviewees agreed for 16 of these stories to be made public, by being published on the Conscious Learning Blog, and/or in this thesis. These stories can be found in Annex 5.2.

2 Surveys

Following the initial DAF 2020 User Survey, mentioned above, the RT designed and disseminated five other research surveys in DAF social learning spaces. These surveys aimed at further exploring effect data created in these spaces, on the basis of the list of indicators we were monitoring.

These surveys were co-designed by the research team. We built them using the software Qualtrics, except for the first one, built on Google Forms. In each case, I analysed the results, and discussed them with Wendy. When it felt useful to write a report, I shared drafts with Wendy for feedback, before sharing them in DAF spaces and on the Conscious Learning Blog where required.

Please see Table 1 for a summary of these surveys and of their corresponding reports, including publication information where relevant.

Table 1: Surveys disseminated in the Deep Adaptation Forum

Survey title |

Code |

Survey dates |

Respondents |

Report title |

Report publication |

DAF 2020 User Survey |

DUS |

Jan. 2 to Feb. 25, 2020 |

168 |

“DAF 2020 User Survey Report” |

Preliminary results were shared on the IFLAS blog on June 8, 2020 (Bendell and Cavé, 2020). The full report was published on June 17, 2022 (Cavé, 2022a). |

DAF Dismantling Racism Training survey |

DRT |

Nov. 19-30, 2020 |

17 |

“DAF ‘Dismantling Racism’ training Final Survey Results: Your feedback” |

The report was shared on Feb.17, 2021, with all participants in the Dismantling Racism course. It was decided not to make it public immediately, but that it could be published together with this thesis. The report can be read here: https://bit.ly/42PYC7D (Cavé, 2021) |

Why did you leave the Professions’ Network? |

N/A |

Sept. 15-30, 2021 |

9 |

N/A |

No report was written, as there were too few respondents. The responses received helped inform Section 2.3.2 of Chapter 5. |

DAF Collapse Awareness and Community survey |

CAS |

June 1, 2021 to Jan.22, 2022 |

58 |

“DAF Collapse Awareness and Community Survey Report” |

The report was published on Feb.28, 2022 (Cavé, 2022b). |

Group Reflections survey |

GRS |

Nov.16, 2021 to Feb.15, 2022 |

17 |

“Views on Unlearning and Radical Collective Change in the Deep Adaptation Forum” |

The results of the GRS and RCS surveys were combined into a single report, published on Sept.20, 2022 (Cavé, 2022d) |

Radical Change survey |

RCS |

Feb.8, 2022 to Mar. 22, 2022 |

15 |

Between July and October 2021, the RT initiated the first DAF Conscious Learning Festival, a series of online activities advertised in DAF as “an invitation to all participants in the Forum, to pay closer attention to what changes may be arising, and what learning may be occurring for us, as a result of participating in Deep Adaptation events, groups and spaces” (Cavé and Freeman, 2021). The various activities organised as part of this Festival aimed at publicly surfacing more of the social learning taking place in DAF, in the hope of fostering more social learning inside and outside the network; and at encouraging DAF participants to become more self-aware of their own learning, in the hope of facilitating deeper personal transformations.

Another important goal of the Festival was to call attention to and celebrate the contributions of volunteers, groups, and other DAF participants to the collective learning taking place in the network.

As part of the Festival, we convened a series of live group calls, open to any participant in and outside DAF. These calls were recorded, and designed to function as spaces for collaborative inquiry and mutual learning. Anyone in DAF was also explicitly invited to offer to host their own webinar or live event, as part of the Festival, which led to two volunteers deciding to do so.

From October to December 2022, we co-organised a second edition of the Conscious Learning Festival, following the same modalities as the first edition (Cavé and Freeman, 2022).

The start of the Conscious Learning Festival was accompanied by the launch of the Deep Adaptation Conscious Learning Blog7, curated by the RT and hosted on the DAF web server. This website aimed to offer insights into the social learning taking place in the various DAF groups, platforms, and regular events, in the hope of fostering more social learning inside and outside the network. An important assumption in doing so was that this information might encourage more self-awareness in DAF participants – and thereby facilitate deeper personal transformations.

The blog enabled anyone to create an account and post content onto it, or comment on existing posts – although any new content needed to be approved by the admin (me). New content could also be published by first being sent over to Wendy or myself over email, or to me via the website’s contact form.

When we heard DAF participants mention interesting insights or resources, we also invited them to publish these on the blog, and offered to help them do it. Recordings of the Conscious Learning Festival webinars were published as new video resources on the blog, with the consent of all participants. Any new research reports we authored were also published there.

At the time of writing, 78 blog posts had been published on the Conscious Learning Blog, by 17 authors.

Wendy and I also convened a variety of group conversations within DAF, which participants agreed could be used as part of the data analysed in this research. At the time of writing, this notably included:

- 12 Conscious Learning Festival webinars (Annex 5.5);

- 20 Diversity and Decolonising Learning Circles (Annex 5.3); and

- 1 feedback call with DAF volunteers who participated in the 2021 Transition US Summit.

We convened each of these calls as social learning spaces, encouraging our own uncertainty within them and encouraging all participants to do the same.

As I undertook this research in DAF, I decided to bring in extra reflexiveness, in the hope of becoming as aware as possible of the effects of my position in this community -both as a member of the Core Team, and as a PhD researcher – in terms of my knowledge production. As I reflected on this, I sensed that my investment in DAF activities affected my value judgements in multiple ways, for instance:

- Because I had held a senior role in DAF since its inception, and thus enjoyed easy access to people as well as a wealth of documents, it would be easy for me to lack humility with regards to any assumptions, hypotheses or theories regarding the network;

- Because I believed in the mission of DAF and invested much time and effort into it, I might pay more attention to what validated my participation, and conversely, lack sensitivity to its shortcomings or to questions about its purpose and relevance, or the worldviews of its participants;

- And because my own socio-economic and demographic positionality was very similar to that of most other participants in DAF, I may lack understanding of how this collective identity (along with forms of discourse or belief systems associated with it) may come across to people from other social contexts.

I also ran the risk of other research participants seeking to confirm – consciously or not – what they believed I might want to hear, particularly with regards to positive assessments of the role of DAF and/or decisions made by the Core Team.

I tried to manage these biases in several ways, without any illusions as to my (in)ability to be impartial.

First, in my regular journaling (Section 2.2.2 above), I strived to remain curious about my perspectives, assumptions, and behaviour, by reviewing my notes regularly and adding reflective comments to them. I tried to hold any emergent sense-making as provisional and with suspicion, particularly when it appeared to confirm what I wanted to believe. Following Marshall (2016), in my journaling as in my conversations with my co-researcher Wendy and others, I took up the practice of regularly scanning inner and outer arcs of attention8, which “offer me opportunities, and challenge me to make what I do, think, feel and experience experimental in some way” (p.54) – without pretending that I have pure access to my own stream of consciousness, which is impossible.

I also tried to be as conscious as possible to issues of power (particularly with regards to decision-making, or the management of meaning) in how they played out in my research, be it in the RT (see Annex 5.6) or beyond. For instance, I tried to make space for mutuality and inclusion of my co-researcher’s ideas and intentions, and for regular reviews and accounting for choices made in the RT. I also shared draft versions of my thesis – and especially of Chapter 5 – with Wendy and other DAF participants for feedback and critique.

I actively sought out voices and accounts of experience that contradicted my understanding of DAF as a “force for good.” I opened up any research conversations with very open-ended questions about people's experience within DAF, without orienting the conversation only towards “positive” aspects of their participation. When uncomfortable experiences or less positive views on DAF were mentioned, I tried to probe them fully. I also initiated interviews with all the individuals I knew who were once involved in DAF and then left, in order to better understand their issues with the network. As a result, several value-creation stories (Annex 5.2) feature less positive comments on DAF and/or the DAF leadership or other aspects, which are summarised in Section 2.3.2 of Chapter 5.

Finally, I convened several conversations with DAF colleagues specifically to share with them results from my research and literature review that challenged the dominant stories and perceptions we had regarding our work (e.g. Section 4.5 of Annex 5.3, regarding the D&D Circle). I saw this both a way to receive their feedback, and as constructive prompts for us to collectively reflect on and question our assumptions.

In the next chapter, I will present the results of the first case study I carried out as part of this research: FairCoop. I will return to the Deep Adaptation Forum in Chapter 5.