Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

Annex 5.4

Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

This annex explores some of the key aspirations and intentions that participants have been expressing within the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF). This is a critical question to investigate as part of using the Wenger-Trayner social learning methodology (Chapter 5).

In order to usefully investigate this question, I will first examine some important elements of discursive framing that the founder and Core Team have used to describe the network’s purposes, during its launch and beyond – in other words, the conveners’ intentions; then, I will turn to the aspirations voiced by various participants and stakeholders in the network, following its creation.

1. Evolution of the DAF framing

In this section, I will argue that DAF’s official framing, as presented in various communications published by participants in the network leadership (especially the DAF Core Team) has evolved over time.

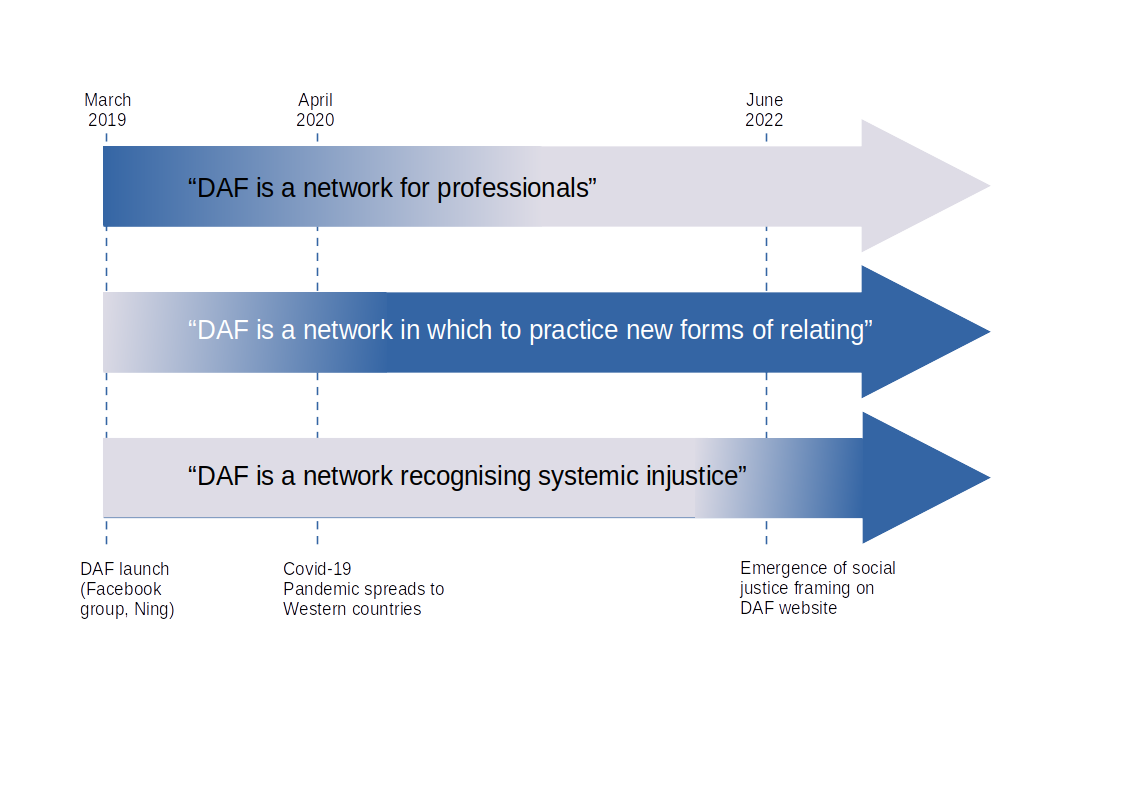

I consider that DAF has been presented following three main discursive framings:

- “A network for professionals”

- “A network in which to practice new forms of relating” and

- “A network recognising systemic injustice”

Figure 16 below charts the relative presence of these three main framings, based on my observations, cross-referenced with a few key events. I then proceed to explain how I have perceived this evolution, below.

Figure 16: Relative presence of three main discursive framings within official DAF communications (dark blue indicates a stronger presence)

1.1 A network for professionals

To better understand how DAF has been framed since its creation, we should look at the texts presenting it to the world. This includes articles written by the founder and other strategic communication pieces authored by the DAF Core Team.

An important text is the first blog post about DAF published by founder Prof Jem Bendell, on March 6, 2019 (Bendell, 2019c). In it, DAF is introduced primarily as an online space in which to engage with the DA ethos and the topic of societal collapse from the perspective of organisations and professional fields of activity:

To extend the glide of our societies and soften the crash, the goal must be for every professional association, think tank, trade union, and research institute, to develop their own work on collapse-readiness. Before that happens, we can connect around the world and support each other to play a role in our professions and locations when the time arrives. It is for these reasons that today we launch the Deep Adaptation Forum.

This blog post also lays an emphasis on DAF enabling collaborative activities, such as hosting online calls, gathering useful knowledge resources, and maintaining an event calendar.

Importantly, this text also mentions the possibility of using DAF to “explore collapse-readiness in all its potential forms, from the practical, to political, emotional and spiritual,” which hints at non-professional contexts. Nonetheless, its general focus remains on individuals wishing to “join regular webinars, seek advice and co-create shared resources for [their] field of expertise.” The text invites the readers identifying with this aspiration to join what may be deemed an epistemological community (Assiter, 1995), rooted in a shared awareness and acknowledgement of the reality of the global predicament:

There is no need to wait for your fellow professionals to wake up to our predicament. There is no need to spend much time justifying yourself. There is no need to rage against ignorance. Instead, we can start to live our truth together now.

A closing paragraph also points to other places in which to carry out conversations on Deep Adaptation, while underlining their characteristics:

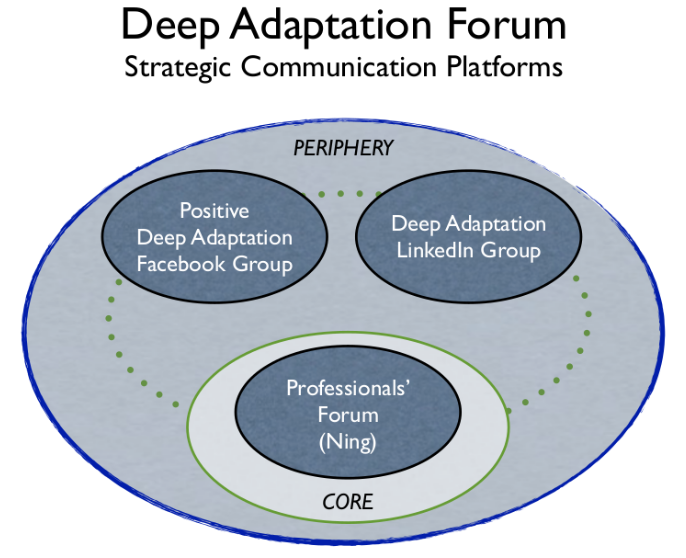

Note that the Forum is the place for professional collaboration. If you simply want to see the latest posts from professionals in this field, join our LinkedIn Group. If you have a general interest but don’t work on it, then join our Positive Deep Adaptation group on Facebook.

This shows that two other online groups dedicated to conversations on DA, hosted by important social media platforms (LinkedIn and Facebook) also existed at the time of the Deep Adaptation Forum.

In order to make sense of this context, it is essential to go back to the history of DAF (see Chapter 5). What is referred to as "the Deep Adaptation Forum" in this blog post is in fact the online space (hosted on the platform Ning.com) which, from October 2019, would be renamed as “the Professions' Network of the Deep Adaptation Forum.”

Prior to the launch of the Deep Adaptation Forum on Ning, Prof Bendell created the Deep Adaptation LinkedIn group in January 2018, and the Positive Deep Adaptation Facebook group a few days before the Ning space. However, from the early days of their work in March 2019, DAF Core Team members referred to to all of these platforms simultaneously under the name “Deep Adaptation Forum,” including in the process of producing a “Strategic Overview and Planning” document from July to August 2019 (DAF Core Team, 2019a), which served as the basis for DAF’s first fundraising proposal.83

Within this strategic document, the Ning space is referred to as the "Professionals’ Forum" (Figure 17) and as a space enabling “Professional Dialogue & Collaboration” (Figure 18). It is also depicted as forming the core of a network of strategic communication platforms also including the Facebook and LinkedIn groups, and as an informational hub connected with various other broadcasting channels.

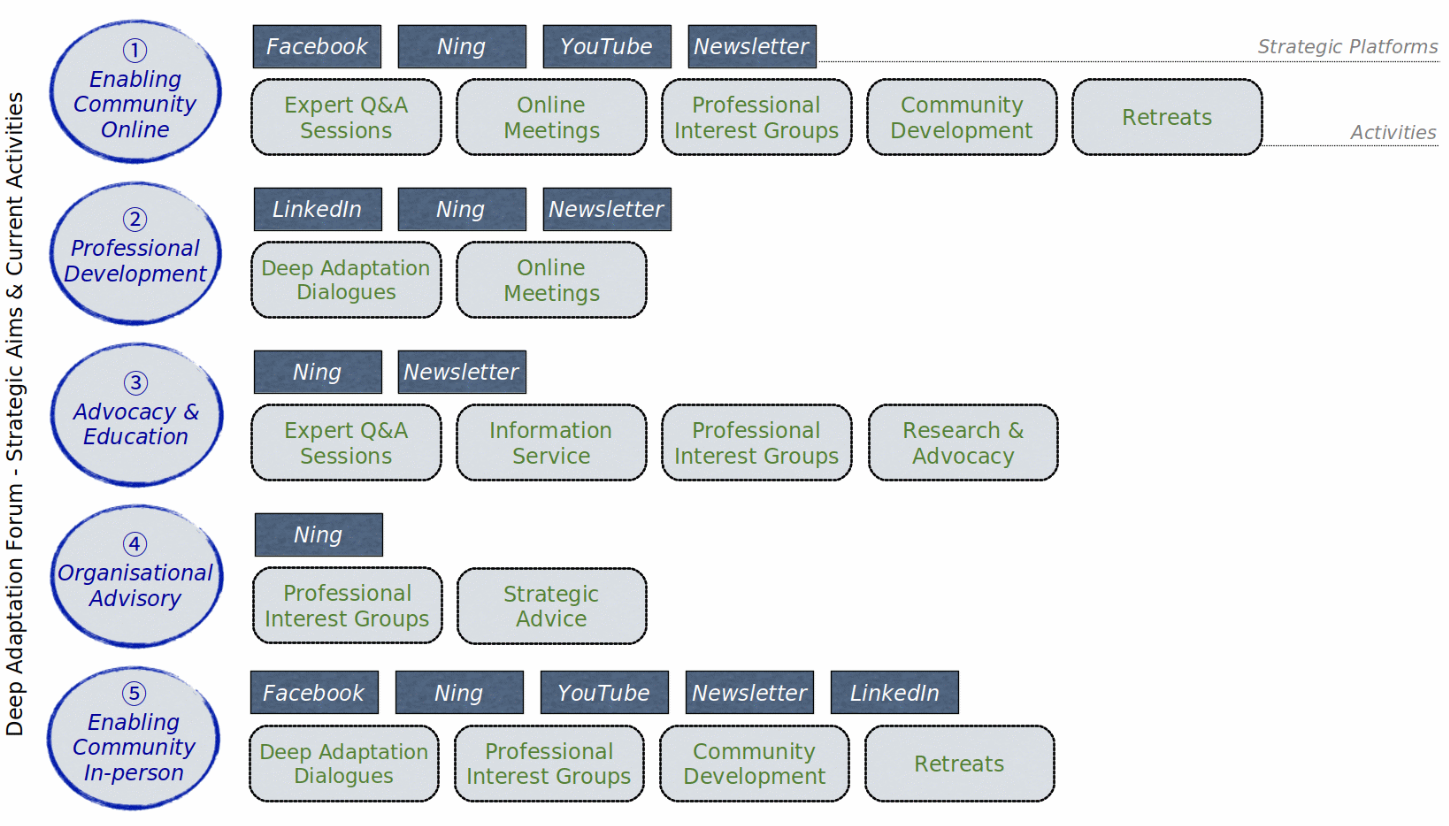

DAF’s strategic communication platforms are presented as serving to enable specific activities, towards pursuing five main strategic aims (Figure 19): “Enabling community online”; “Professional development”; “Advocacy & education”; “Organisational advisory”; and “Enabling community in-person.”

Figure 17: DAF Strategic communication platforms (August 2019)

Figure 18: DAF Strategic platforms articulation (August 2019)

Figure 19: DAF Strategic aims & current activities (August 2019)

As for the Facebook group, it is described (p.20) as “a a crucial and very active platform for people all over the world to connect as their awareness develops regarding our climate predicament, and the Deep Adaptation framework.” It enables “mutual emotional support” and “an open dialogue,” and inspires the creation of local or regional groups and initiatives. Finally, the LinkedIn group is framed as “a peripheral layer of the DAF’s strategy to enable deeper conversations in all professional fields around Deep Adaptation Ideas” and as a channel to “guide more participants into the Professionals’ Platform (Ning).”

Examining the early articulation of strategic aims and activities in the “Strategic Overview and Planning” document is important because it highlights the main elements of framing articulated by the DAF Core Team in the early days of the network. Besides, this document and framing were shared with all DAF volunteers as an official communication piece, which was discussed in volunteer calls at the time. Its key messaging – including the organisational aims and charts above – were also incorporated into the “DAF 101,” an introductory online document shared with all newcomers to the network, mainly between March 2020 and January 2021 (DAF Core Team, 2020).

While this framing includes areas of activity such as online and offline community-building, as in the blog post examined above, it is centred on needs and activities relevant to professionals. “Mutual emotional support,” for instance, is shown as merely belonging to the more “peripheral” Facebook group. This explains the early conflation of the name “Deep Adaptation Forum” with what then became known as the “Professions’ Network”84.

1.2 Cultivating new forms of relationality

Nonetheless, in parallel to this focus on enabling communications among professionals, another important framing was also cultivated: that of fostering new forms of relationality between DAF participants and beyond.

The earliest text bringing this to light is another blog post by Jem Bendell (Bendell, 2019b), published two months prior to the the one mentioned above. In it, the author presents current and future suffering brought about by societal collapse as an invitation to

turn away from frantic chatter or action, relax into our hearts, notice the impermanence of life, and let love for this momentary experience of life in all its flavours flood our being and shape our next steps.

According to him, “Expressing that aspiration in our words, actions and inactions may invite people who are fear-driven to put down their microphones for a time and join people living from love.”

Bendell encourages the reader to embody this aspiration by embracing “radical” hope (as opposed to more “passive” or “magical” hope, for example with regarding to the possibility of avoiding collapse); engaging with spiritual perspectives on the global predicament, including the acceptance of death and impermanence; and highlighting the notion of reconciliation as a necessary additional pillar within the DA framework and ethos, and a way to practice an “inner adaptation to climate collapse” without which “we risk tearing each other apart and dying hellishly.”

This framing is further developed in another blog post, published less than two weeks after launch of DAF, and co-authored by Jem Bendell and another DAF Core Team member, Katie Carr (Bendell and Carr, 2019). In this article, titled “The Love in Deep Adaptation – A philosophy for the forum,” the authors present DA as a process involving both “collapse-readiness” and “collapse-transcendence”:

Collapse-readiness includes the mental and material measures that will help reduce disruption to human life – enabling an equitable supply of the basics like food, water, energy, payment systems and health.

Collapse-transcendence refers to the psychological, spiritual and cultural shifts that may enable more people to experience greater equanimity toward future disruptions and the likelihood that our situation is beyond our control.

As part of the latter, the authors identify the need to relinquish the widespread delusion in modern societies that every individual is a self-contained being, separate from other human beings and from nature. Because of a process of cultural indoctrination into this mindset of separation, modern humans tend to “other” people and the natural world. This process of “othering” leads to “dampen[ing] any feelings of connection or empathy to such a degree that we can justify exploitation, discrimination, hostility, violence, and rampant consumption.”

The need to let go of this delusion and the harmful relational attitudes it begets is all the more urgent that they are linked to the psychological need to “map and control reality in pursuit of feeling safer or better.” As a result, the authors express concern that if many people start believing they are “entering a period where there will be more disruption and less ability to control,” for example due to societal breakdown, they are likely to seek safety by means of an increasingly violent process of othering. The remedy to this is “to feel and express love and compassion,” cultivating a “loving mindset” by which “we experience universal compassion to all beings.”

Bendell and Carr conclude their article by framing this form of “collapse-transcendence” as a philosophy to be practised within DAF. This should be done by following the three principles of “return[ing] to… compassion… curiosity… and respect.”

Since its publication, “The Love in Deep Adaptation” has been widely shared and cited as a foundational text by volunteers within DAF (Freeman, 2021) – as well as mentioned in subsequent texts co-authored by either or both of its authors (e.g. DAF Core Team, 2019b; Bendell and Carr, 2021). Indeed, as its title suggests, this article encapsulates the core values and principles that DAF participants have since then been invited to use as inspiration and guidance in their engagement, alongside the “4 R’s” of the DA framework (see Chapter 5). For example, a link to this blog post appears in the welcome message seen by new members joining the DA Facebook group, and in the group’s “Rules and guidelines” file.

But the influence of this framing makes it much more than a mere code of conduct. For example, it is clearly reflected in DAF’s mission statement, displayed on all platforms and presentation documents: “Embodying and enabling loving responses to our predicament.”

Besides, as presented by Bendell and Carr in a later publication (Bendell and Carr, 2021), these values and principles have also constituted the foundation for establishing – shortly after the launch of the network – an influential community of practice within DAF, focused on “group facilitation in the face of disruption.” The facilitators within this group, initially under the leadership of Katie Carr, have been experimenting with and developing various facilitation modalities enabling groups of participants to address the mindset of separation, and to foster the “loving responses” that are a central part of the network’s mission statement. Since its creation, DAF facilitators have been regularly hosting several free online gatherings centred on practising these modalities – such as Deep Relating or Deep Listening circles – which seem to have had a lasting impact on a number of participants (see Chapter 5).

Gradually, particularly over 2020 to 2021, DAF’s official framing came to place an increasing emphasis on relational aspects. However, this is not to say that “collapse-readiness” was entirely discarded in favour of “collapse-transcendence.”

For example, DAF’s main introductory page, first published on the DAF website in November 2020 (DAF, 2020b), presents DAF as a network open to all, and barely mentions professional fields of expertise as a key focus area any longer. Nonetheless, it still introduces DAF as enabling various forms of collaboration, dialogue, community-building, and peer support groups. Compared to the earlier purpose statements, it highlights the importance of “connection, dialogue, and generative collaboration, rather than just information sharing.” It also speaks to the need to address the “extreme forms of collective ‘othering,’ or even fascist responses” which could arise from fear and anxiety in a context of collapse.

From what I was able to observe, the evolution of DAF’s framing beyond addressing the needs of professionals can be ascribed to a variety of factors, most importantly:

- changes in network leadership, including core team staffing;

- the stronger focus placed on group facilitation processes within DAF, in response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic; and

- decreased member engagement on the Professions’ Network, possibly due in part to intractable issues with the user interface (see Cavé, 2022b), as opposed to more robust activity on the much larger DA Facebook group.

1.3 Towards more attention for social justice

Finally, a third noticeable inflexion in the network’s started taking place from mid-2022, toward a clearer acknowledgement of the social justice aspects of the global predicament, and of the differentiated impacts of societal disruptions it brings about around the world. This evolution took place as a result of a combined intention on behalf of the DAF Core Team and other active participants in the network, including Holding Group and D&D circle members.85

In June 2022, a new webpage was created on the DAF website specifically to call attention to underfunded grassroots initiatives, mostly in the Global Majority world, in need of direct support (DAF Core Team, 2022e). Any network participants could sponsor a particular project for it to be listed on the page, as long as met the specified criteria, which would also lead to the initiative being advertised in monthly DAF newsletters. Updates on the project were to be shared with the rest of the network on a quarterly basis.

The following month, two Holding Group members teamed up to produce another webpage, with the purpose of foregrounding “invisibilised voices on collapse” – i.e. lived experiences of societal collapse (Virah-Sawmy and Jiménez, 2022). These stories are told by individuals and collectives who have experienced various forms of collapse as a result of the history of European colonialism since the 15th century. They constitute a vivid reminder that the potential collapse of the modern industrial society cannot be disentangled from the traumatic history of conquest, slavery, genocide, exploitation and ecocide that has enabled this society to establish its domination around the planet. They are also a testimony to the resilience and resourcefulness of people in the face of centuries-long oppression and the breakdown of their traditional ways of life.

Simultaneously, and most significantly, the main section on the website introducing DAF was also revisited (DAF, 2022c). For the first time since the creation of the network, it laid a strong emphasis on the experiences of collapse of racialised and Indigenous communities, and of non-human species, as a result of the aforementioned history. It also expressed the wish to stand in solidarity with all affected, and to interrupt processes perpetuating this injustice.

Finally, later that year, another section on the website was launched to provide rebuttals to certain comments that were occasionally voiced on the DAF Facebook group, by participants often unaware of the political implications of their words. The page, titled “Avoiding authoritarian responses to our predicament” (DAF Core Team, 2022a), provided resources enabling readers to understand why advocating population reduction efforts or curbs on individual freedoms, for instance, was not coherent with DAF’s ethos and mission statement.

As I will mention below, there are signs indicating growing support and awareness for this framing within DAF as a community. However, it is unclear at the time of writing to what extent this evolution was translated into action, given that data collection through surveys and interviews occurred largely prior to it. It is worth mentioning that in spite of much communications efforts, direct support for the solidarity projects publicised through these channels had remained limited up to the time of writing.

2. Participants’ aspirations

What have been some of the main aspirations voiced by network participants? To what extent do they correspond to the framing articulated in DAF’s official documents?

I will answer these questions by examining several instances of collectively articulated aspirations.

2.1 A conversation in the DA Facebook group

Anyone spending time in the DA Facebook group, DAF’s largest and most dynamic platform (about 15,000 members at the time of writing) will soon realise the diversity of participants’ topics of interest.

A particularly revealing example was a rich conversation in the DA Facebook group, initiated on September 16, 2021, and which involved 31 people posting 111 comments86. Of these participants, eight could be considered volunteers actively involved in the network; the others were not active as DAF volunteers, but a significant proportion of them took active part in the discussions on the Facebook group.

The opening poster expressed regret at the energy spent in the Facebook group on “accommodating new participants who ask cycles of common questions,” instead of engaging in more productive collective endeavours, such as providing “an instrumental theory or critical commentaries on solutions” with regards to various issues (from “resilient communities and food systems” to “reimagining kinship and family patterns”), and creating more “active study and affinity groups” researching specific concerns before publishing recommendations broadly. He also wondered whether DA should “becom[e] a cohesive movement.”

The conversation that followed exemplified the variety of aspirations and understanding of DA among DAF participants. Important themes that emerged were:

- DA as a vehicle to “move through the emotional (or spiritual…) dissonance that comes in living at the conclusion of industrial civilisation,” providing safe spaces for individuals to express their feelings of grief and vulnerability, reconcile themselves with death, and find solace;

- DA as “a problem-filtering hub that contains multitudes of ‘solutions’ based on individuals and their local context,” non-prescriptive, and built on the foundation of a common framework and ethos that encourages personal initiative, collaboration and self-organisation;

- DA being fundamentally a democratic, anti-authoritarian framework;

- DA being about “adapting and working within or around local institutions” such as municipalities and community organisations, and developing crisis leadership in order to “[think] ahead about the implications of the obsolescence of conventional institutions”;

- The need for more people in DAF to articulate “structural analysis of the known avenues to a better world” with “an immediate jump into radical actions to make any of it real, extend the glide, man the lifeboats and save lives”;

- The importance of providing professionals with tools and resources to disseminate the DA ethos and thinking within their industry;

- DAF as a container for “spiritual inner work”;

- DAF as providing a wealth of informational resources to its participants, although these resources should be better organised and catalogued;

- The need to document the various initiatives undertaken by DAF participants as an inspiration for others in and outside the network...

Interestingly, while was present the theme of action within given professional and organisational fields, that of cultivating new forms of relationality was not. Instead, many participants lay the emphasis on DAF as a vehicle for self-organisation, local activism, and practical forms of action aiming at reducing harm.

In order to gain more clarity on the main aspirations of DAF participants with regards to their involvement, I will examine the results of several consultation processes that took place over the past two years, as well as a summary of relevant information I collected in this research project by means of several surveys.

2.2 Consultation processes

Strategy Options Dialogue (2020)

Since DAF’s creation, several strategic consultation processes have been carried out within DAF, in collaboration between volunteers and Core Team, with the aim of surfacing participants’ aspirations for the network.

The first of these efforts was the 2020 Strategy Options Dialogue, which took place between February and April 2020. Through a combination of written submissions and live group calls following an emergent “Open Space Technology” format, involving nearly a hundred participants, this process aimed at investigating the three following questions:

- What range of activities should be pursued under the Deep Adaptation (DA) umbrella, and what are the different possible rationales for pursuing those activities?

- What specific role could an emerging international network play in this context, and on what kind of timescale?

- What are the key strengths of existing structures that can be deployed to serve these objectives (including, possibly, implications regarding organisation, governance, and funding)?

The outcomes of these conversations were summarised by volunteers into a document (DAF, 2020a) presenting the dialogue participants’ main aspirations for the network. The latter were grouped into six main strategic themes, alongside list of potential action items. These themes listed below in decreasing order of importance for participants:

- Development, Training, and Dissemination

- Community-building

- Collaboration and networking

- Leadership and governance

- Evolution of consciousness

- Collapse-readiness

In terms of the two areas of official DAF framing discussed in Section 1.1 above, the “relational” aspects of DA generated more discussion and enthusiasm among participants, while “professional” areas of activity were less popular.

We in the Core Team then reviewed this summary document, and published a response highlighting the action item ideas that appeared most feasible for us to support actively, in view of available time and resources – as well as other ideas on which we invited volunteers to take the initiative. The Core Team’s response primarily featured action ideas in the realms of:

- emergent and decentralised governance (e.g. self-organised circles and local groups)

- knowledge production and dissemination (e.g. peer support and training)

- co-production and dissemination of ideas (via a new collaborative DAF Blog)

- spirituality

- anti-racism and other forms of social injustice

Various new initiatives took place in the network as a result of this process, with various degrees of success – for example, the D&D circle was created shortly thereafter, as was the DAF Blog. The results of a follow-up questionnaire which I sent to all dialogue participants at the end of the process (Cavé, 2020) spoke of participants’ increased awareness of the diversity of perspectives and opinions with regards to what main areas of focus should be within DAF. However, the dialogue also led several respondents to doubt the network’s “capacity to be a conduit for leadership” or its focus on practical solutions to the global predicament.

Learning and (un)learning, and Strategy Options Review (2021)

The following year, two new consultation efforts took place. In March 2021, volunteer Kimberley Hare led a process involving 60 DAF participants, which aimed at identifying key aspirations among the DAF community. Its focus was on practical actions, within the general theme of “learning and (un)learning.” Among other findings, her report (Hare, 2021) highlighted that a “small but vocal minority felt that DA was overly focused on the ‘inner’ aspects of DA and [that] much more support was needed in the practical dimensions” (p.6) and that the Core Team should encourage more real-world action within the purview of DAF. Respondents also expressed a wish for more participation diversity and less elitism, as well as better signposting and resource libraries.

Importantly, a large number of respondents asked for more “spaces and places for connecting, relating and listening” in DAF, both online and offline. The number of suggestions of this type appears to correspond with the evolution of the official DAF framing towards encouraging deeper forms of relationality, which was taking place at the same time (Section 1.3).

The results from Kimberley Hare’s report were integrated into a second consultation process, which followed soon after: the Strategy Options Dialogue Review (April-May 2021). This effort, initiated by the DAF Core Team, aimed at examining each of the six themes that had emerged from the 2020 Strategy Options Dialogue. DAF participants were invited to co-create a shared document charting existing initiatives for each theme, as well as those that they aspired to see.

The review process confirmed the relevance of the six existing themes, and a seventh one also emerged (“Communications”). Its outcome was the creation of a new interactive page on the DAF website (DAF, 2021), featuring a map listing each of these themes along with potential self-organised affinity groups which could be formed by anyone willing to do so, to meet the aspirations of the community. Guidelines for such “DA Circles” were published simultaneously. The webpage included instructions to join the DAF Slack workspace, which had by then developed into the network’s primary space for connection among volunteers. Unfortunately, the complexity of Slack as a tool and the lack of adequate training resources severely limited the creation of new circles.

These two consultation efforts showed that in the first half of 2021, there was high demand for online and offline spaces in which to practice new forms of relationality, as well as several existing regular offerings provided within DAF to address such needs. In comparison, there was little to no demand for more active engagement with various professional or organisational fields. Unmet needs included:

- more informational resources and learning-oriented spaces;

- more attention toward local and practical forms of collapse adaptation;

- more external- and internal-facing communications;

- and easier ways to set up self-organised project or peer support groups.

New initiatives aiming to address these aspects emerged subsequently (such as DA Circles, or the DAF Conscious Learning Blog). Local and practical dimensions of collapse anticipation remain less central than relational and psychological aspects within DAF, at the time of writing.

“Dreaming and visioning” strategic process (2022)

Another consultation was organised between April and July 2022 by the Core Team, with support from a DAF volunteer. This process involved a series of strategic conversations within the Holding Group, the Core Team, and in a gathering of volunteers and Core Team members. It also included four polls published in the DA Facebook group, asking for people’s thoughts on the value they had drawn from DAF thus far, and what functions they were most hopeful DAF might fulfil in the future.

From the results of one of these polls, it appeared that respondents were most keen to:

- more easily connect with other DAF participants locally;

- share and learn about practical aspects of DA; and

- collaborate with other participants on inspiring projects.

On the other hand, these respondents were least keen to:

- find and give emotional mutual support;

- engage in activism with other participants; and

- bring DA into their profession.

Although the polls did not collect information as to respondents’ degree of involvement in DAF, the number of responses to this particular poll (191 votes) suggests that most of them came from more peripheral DAF participants. This makes these results interesting, as the other consultation efforts mentioned above, on the contrary, tended to involve more active DAF volunteers and participants.

These results confirm those gathered through the “DAF Collapse Awareness and Community Survey,” to which I return below: indeed, more peripheral participants (who do not take on volunteering roles) tend to have greater interest in practical forms of adaptation to the prospect of societal collapse than to deeper relating or activism.

This information was shared with the network volunteers, over twenty of whom then took part in a follow-up process over videoconference, during July 2022. The purpose of the call was to surface, by means of a somatic and relational process, these participants’ aspirations regarding the future of DAF. The Core Team then distilled the proceeds of this call into a series of “commitments to action and being,” comprising several suggested orientations (DAF Core Team, 2022c):

- Connect with individuals, networks, and grassroots organisations doing important DA-aligned work around the world, particularly in marginalised and/or Global South contexts, in order to bring about mutual learning between them and DAF participants, and foster respectful support for their initiatives (including materially and financially);

- Liaise with sister networks and organisations that are aligned with the DAF charter, in order to explore how the modalities and ways of organising developed within our network may travel, like spores or seeds, and be adopted/adapted within other contexts and groups... while paying attention to what these counterparts may offer in return;

- Engage proactively with the needs of younger generations, particularly around integrating eco-anxiety and finding ways of generatively responding to our common predicament;

- Support the emergence of many more locally rooted collectives around the world that explicitly bring the DA ethos of mutual support and compassionate action into their lives, livelihoods and projects;

- Encourage the start of new educational and peer-support endeavours on behalf of DAF participants, by relying on an emerging e-learning platform and other means (e.g. public events), in order to foster more creativity and deeper learning within our community.

These proposed orientations were then discussed in another call to which all volunteer participants in the strategic process were invited, to invite feedback. There appeared to be broad agreement with these suggestions. Considering the prominence among these of concerns for various forms of solidarity, particularly across generations and social classes, these results support my view that an attention to issues of social (in)justice gradually became more present within DAF.

2.3 Survey results

Beyond the aforementioned consultations, two surveys created within the research team I have been part of within DAF have also queried participants on their aspirations about the network. One of these surveys focused more specifically on further distinguishing differences between the aspirations of DAF participants, depending on their degree of engagement in the network. Another investigated whether the idea of “radical collective change” meant anything to participants, with regards to their engagement in DAF.

Do people’s aspirations vary, depending on their degree of involvement in the network?

Through the “DAF Collapse Awareness and Community Survey,” between June 2021 and January 2022, the research team gathered responses from 58 DAF participants (of which 33 self-identified as non-volunteers) to the question of the reason for their involvement in the network, among other topics. In particular, this survey examined areas of overlap and difference between three types of respondents:

- those who were most actively involved in DAF (as very active volunteers or members of the Core Team);

- more occasional volunteers;

- and those who were not volunteering in the network.

I will present here a summary of some key findings from this survey. For more details, please read the full report in Cavé (2022a).

Key purposes for being in DAF

Across all three categories of respondents, the two purposes that were most important overall were “To find a sense of community and belonging” and “To be well informed and make sense of the topic of societal collapse.” The two purposes that were least important overall were “To discuss societal collapse from the perspective of political change” and “To discuss societal collapse from the perspective of [one’s] professional activity.”

The purposes that most volunteers and active participants had in common were “To be of service to others,” and - in equal proportion - “To take part in local forms of community-building,” “To connect deeply and meaningfully with others,” and “To engage in the inner work of personal transformation.” These last three purposes were much less present for non-volunteers.

Volunteers and active participants were also much more interested in “online forms of community-building” than non-volunteers; but they were less keen to “find out how to prepare [themselves] and/or [their] family for societal collapse” or “to be well informed and make sense of the topic of societal collapse” than non-volunteers.

The most actively involved participants also had preferences that were slightly distinct from those of most volunteers: “To be of service to others” and “To connect deeply and meaningfully with others” were the top priorities, while “To find a sense of community and belonging” and “To take part in local forms of community-building” were less important than for volunteers.

From this data, it seems likely that most active volunteers in DAF tend to have different purposes for being in DAF than non-volunteers: they have a stronger focus on being of service, connecting meaningfully with others, and engaging in inner work as well as community-building.

As for non-volunteers, they are more likely to seek information, as well as guidance on how to prepare in practical terms for societal collapse.

A sense of community and belonging

Responses to other questions in the survey showed that all volunteers and active participants said they experienced a sense of community and belonging in DAF, and that this feeling was very important to them. Interestingly, this was also the case for non-volunteers: they, too, experienced a high sense of community and belonging, which was very important to them.

As for those who didn’t experience a sense of community and belonging (8% of all respondents), most of them feel “somewhat” or “very much” keen to do so. Only a small minority had no interest in being part of DAF as a community.

It seems safe to conclude that a very important aspect of respondents’ participation in DAF has to do with experiencing DAF as a community, or wishing to do so. This confirms the predominance of “finding a sense of community and belonging” as a key purpose for participants to engage in this network.

Types of community

Finally, another question investigated whether respondents were most keen to be part of a community of “engagement” (based on a sense of active involvement with others); “imagination” (based on a sense of belonging to a larger picture or landscape); or “alignment” (based on a sense of common ways of behaving in the world, or coordinated action in view of a common purpose).

Interestingly, each broad category of respondents placed the emphasis on a different mode of belonging:

- Non-volunteers were overwhelmingly more interested in “being part of a network of people with similar values, interests, and visions of the future” (Imagination), which is perhaps not surprising given that by definition such respondents tend not to regularly connect or coordinate their activities with others in DAF;

- Volunteers had more widely distributed preferences, with slightly more interest in “being part of a network of people coordinating our efforts for a common purpose” (Alignment);

- As for the most active participants, they largely favoured the statement “regularly connecting with people I appreciate in forum discussions, online calls and/or shared projects” (Engagement). Again, this might not be surprising, considering that these respondents tend to be most actively involved in leadership roles within DAF, and as such, take part in a number of projects and conversations on a regular basis.

These survey results confirm that DAF participants’ aspirations for being in the network and forming part of the same community vary depending on their degree of involvement. They also corroborate the data from consultation processes that showed a strong interest among non-volunteers for more local and practical forms of adaptation to societal collapse, while active volunteers have a stronger interest in collaborative activities and in cultivating deep and meaningful relationships with others. Finally, this survey shows a lack of interest overall in more professional or political forms of engagement from respondents, in contrast to the importance of being well informed, and feeling part of a community.

Do participants aspire to bringing about radical collective change through engaging in DAF? If so, what kind of change might this be?

Through the “Radical Change Survey,” between February 8 and March 22, 2022, the research team gathered responses from DAF participants to questions exploring their approach to the notion of “radical collective change,” and whether this notion was relevant to them with regards to their involvement in DAF. There were 15 respondents, of which 10 were “active participants or volunteers,” 3 were “occasional participants or volunteers,” and 2 were “very occasional or rare participants.”

I will summarise here some interesting findings from this survey. For more details, please read the full report (Cavé, 2022d).

When asked to describe their conception of what radical collective change would be needed in the world in the face of the global predicament (regardless of whether it could be achieved or not), respondents to the RCS questionnaire voiced three main types of aspirations. In decreasing order of importance, these were:

- Orienting towards connection, loving kindness and compassion towards all living beings: such change would be about more compassionate ways of being and relating, involving the creation or restoration of fairer communities, as well as reaching better attunement to other-than-humans and the Earth;

- A transformative shift in worldviews and value systems: such change would involve reaching a recognition of the deep flaws, injustice and destructiveness permeating modern societies, new ways of finding meaning, and humanity embracing less arrogant and more biocentric perspectives;

- A radical reshaping of political and economic structures: such change would bring about radically new economic and political systems, from the global level to down to a renewed reliance on local, autonomous and democratic communities, detached from unfair and destructive global systems.

For each of these main aspirations, a majority of respondents considered that their involvement in DAF was helping - if even on a tiny scale - to bring about such forms of radical collective change. Besides, most of them also tended to consider themselves as actively contributing to this change taking place, notably through engaging in a process of personal “unlearning.”

It therefore appears that a large number of the most active participants in DAF view the pursuit of radical collective change as an important aspect of their engagement in the network, although they tend to emphasise the small scale on which any such change may be taking place thanks to DAF and/or their own participation. It is also important to note that the primary form of change that such participants are pursuing corresponds to the second category of framing (“cultivating new forms of relationality”) I have identified as prevalent in early DAF communications (Section 1.2).

However, a minority of respondents found the question of radical collective change irrelevant, meaningless, or impossible to address. As most of them self-identified as active DAF participants or volunteers, this seems to indicate that people may choose to become actively involved in DAF regardless of any wishes or expectations for social change.

3. Conclusion

I have shown that the purpose of DAF was originally introduced by its founder using two main framings: as a network in which to engage with the DA ethos and societal collapse from the perspective of organisations and professional fields of activity; and as a space in which to cultivate new forms of relationality, overcoming separation, and fostering compassion and loving kindness.

The former reflected a strategic intention to structure the core of DAF activities around a particular platform, initially named “The Deep Adaptation Forum,” and which later became “The Professions' Network.” However, this platform did not fully live up to its mission. Partly as a result, the second framing gradually grew in importance within official communications in DAF.

This relational framing was later complemented with a third one, focused on addressing aspects related to the effects of global systemic injustice.

In parallel, participants engaging in the various DAF platforms expressed an interest in a number of topic areas. While some were very much aligned with either of the two main framings described above, others also voiced aspirations that did not readily fit within either of these topics. In particular, more peripheral participants especially expressed a desire for more local community-building efforts, and wished to find more spaces in which to learn about forms of practical preparedness to societal collapse.

This is not to say that none of these other topics have ever been explored and acknowledged as relevant within DAF's official channels. However, they were originally less central within DAF's official framing, which has gradually evolved to incorporate a greater variety of concerns. Besides, the outcomes of various consultation processes between 2020 and 2022 indicate aspirations for more attention to these areas within the network. These outcomes also show the low interest for forms of intervention within professional and organisational fields on behalf of most participants, in contradiction with the network’s original framing.

The history of these strategic consultations speaks to a continued intention, on behalf of the DAF Core Team, to foster self-organisation and support a wide variety of endeavours throughout the network, following a particular ethos - as opposed to driving participation towards meeting any particular set of goals. However, the complexity of this mode of organisation (which breaks from more conventional social movement or non-profit practices) has been reflected in the difficulty for spontaneous groups to emerge and persist in time.

Another important finding, originating from the results of two surveys investigating participants' aspirations, is that intentions for engaging in DAF vary depending on one's degree of involvement in the network.

Non-volunteers tend to be more interested in being well-informed about societal collapse, and learning about practical ways to prepare themselves and their loved ones. For them, feeling they are part of a network of people who have similar values, interests, and visions of the future (a "community of imagination") is an essential reason for being in DAF. Very active participants, on the other hand, are keen to be of service, and to connect deeply and meaningfully with others. Regular occasions to connect with others they appreciate, in forum discussions, online calls, or shared projects (a "community of engagement") is much more important to them.

Overall, regardless of one's degree of involvement, finding a sense of community and belonging is an essential reason for being in DAF. However, for deeply involved participants, cultivating important relationships in the network is a particularly critical aspiration in this regard. Many of these participants have also articulated a deep commitment to facing issues of systemic injustice part of their involvement in the network, which eventually opened a third area of discursive framing for the network.

Besides, the results of another survey show that for many active participants, being in DAF aligns with a pursuit of radical collective change, in the form of enabling oneself and others to orient towards connection, loving kindness, and compassion towards all living beings. This aspiration overlaps closely with DAF's relational framing, which has become more fundamental to the network’s mission than that of fostering professional or organisational change. Other participants also aspire to generate transformative shifts in worldviews and value systems, or - to a lesser extent - helping to radically reshape political and economic structures.

Nonetheless, a number of active DAF participants and volunteers do not find it relevant to frame their participation as part of an aspiration for radical collective change. Further research would be needed in order to better understand the key narratives by which such participants justify their involvement.