Chapter 1. Introduction: Qu'y puis-je ?

Chapter 2. Research context: Locating this study in the existing literature

Chapter 4. Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

Chapter 5. Different ways of being and relating: The Deep Adaptation Forum

Chapter 6. Towards new mistakes

______________

Annex 3.1 Participant Information Sheets

Annex 3.2 FairCoop Research Process

Annex 3.3 Using the Wenger-Trayner Evaluation Framework in DAF

Annex 4.1 A brief timeline of FairCoop

Annex 5.1 DAF Effect Data Indicators

Annex 5.2 DAF Value-Creation Stories

Annex 5.3 Case Study: The DAF Diversity and Decolonising Circle

Annex 5.4 Participants’ aspirations in DAF social learning spaces

Annex 5.5 Case Study: The DAF Research Team

Annex 5.6 RT Research Stream: Framing And Reframing Our Aspirations And Uncertainties

Not everything that is faced can be changed.

But nothing can be changed until it is faced.

- James Baldwin (1962)

In this chapter, I will describe the research and diagnostic process I carried out with several participants in FairCoop, and which led me to focus on the factors that appear to have interrupted the social learning that was taking place, leading to the near-breakdown of this community. These factors have to do with certain ways of doing (operations, strategy, etc.) and with ways of being (culture, mutual care, approaches to conflict, etc.). Arguments in this chapter will mainly draw from the literature on democratic and emergent forms of organising.

I had been keenly interested in FairCoop since I first learned about its existence, in 2017 – and of its success: in its heyday, this community brought together thousands of activists in its online working groups, and in over 50 local groups around the world, focused on creating social change from the bottom up.

The key missions of this community, which I found articulated on the landing page of its website, resonated with my views as regards the radical collective change that I believed was needed on the global level, in the face of our predicament. I am referring in particular to the call for an “integral revolution”:

A deep and comprehensive transformation of all parts of society, including its values and structure. The new, self-managed society is based on autonomy and the abolition of all forms of domination: the state, capitalism, patriarchy, and all other forms that affect human relationships and with the natural environment. Conscious and strategic actions are needed to compost the obsolescent structures and recover those values and qualities that enable us to live a life in common. As the most promising entry point for the collective change we see a new economic system. This is giving people the opportunity to finally exit the vicious circle of capitalistic enslavement and its side effects, to find space for new ideas without boundaries and make possible the switch to a healthy life in balance with nature. (FairCoop, 2021)

The other principles in the “What really moves us” section of that page – about disobedience, open cooperativism, decentralisation, and a stateless democracy – equally spoke to me. Indeed, I believed that shifting to a new economic and political paradigm, away from various forms of domination, was critical to the survival of humanity on this planet – and to the survival of millions of other species.

Another aspect of FairCoop that called out to me, due to my interest in alternative exchange systems, was the cryptocurrency FairCoin. Based on an innovative “proof of cooperation” technical infrastructure, this electronic currency was a keystone of the FairCoop community. Contrary to Bitcoin and its energy-consuming proof-of-work algorithm, FairCoin had a negligible environmental impact, and was designed specifically to empower communities in a fair and decentralised way (König et al., 2018). This felt like a revolutionary technology to me.

My interest in FairCoop deepened while I lived in Athens, Greece, between July 2018 and March 2019. During that time, I lived in the neighbourhood of Exarcheia, a famous hotbed of rebellious, anarchist spirit. I was able to visit FairSpot, a shop which worked as a meeting place for FairCoop activists hailing from various local nodes around Greece and abroad, and in which a variety of local products could be bought using fairoins stored on an electronic wallet. These encounters gave a very concrete feel to the words of FairCoop’s integral revolution manifesto. I also heard stories about the bravoury of FC founder Enric Duran, who stole half a million euros from commercial banks in protest against the corruption of the financial system, invested all of these funds into cooperative projects like FairCoop, and started living underground to escape from the Spanish judicial system (Duran, 2008; Annex 4.1).

Inspired and full of admiration, I decided to carry out a case study on FairCoop as part of my research on radical social change.

FairCoop (FC) was an offshoot of the Catalan Integral Cooperative (CIC). The CIC was a project founded in Spain in 2010, which officially stopped functioning in mid-2019.

Building on the tradition of cooperativist and anarchist organising in Catalonia, and drawing strength from the 15-M (Indignados) anti-austerity movement from 2011, the CIC was “a transitional initiative for social transformation from below through self-organisation” which “worked towards a so-called ‘integral’ revolution, which aims to create the conditions, while also supporting all the necessary social and economic elements for a transition towards a post-capitalist society” (Balaguer Rasillo, 2021, p. 4). It gave rise to many groups and initiatives that were still active at the time of writing, including a network of a dozen independent and autonomous Catalan social currencies: the Ecoxarxes.

FC can be viewed and defined in different ways, depending on one’s focus. This is how FC introduced itself on its Wiki (FairCoop, no date b):

FairCoop is a global movement of people who are in the process of setting up a self-managed, cooperative, supportive, ecological, and autonomous socioeconomic ecosystem for the transition to alternative models of organization based on justice and equity. […]

FairCoop supports the values of cooperatives and put most of them also into practice but FairCoop itself doesn’t have the legal status at all and goes even beyond that traditional approaches of a Coops [sic]. FairCoop has also some characters of a platform cooperative but also here goes beyond that definition due to its diversity of tools and apps. It has traits of a grassroots movement but as its also fueled from the global level and aims to create an alternative and parallel system to the existing one instead of changing the system itself this definition doesn't completely fit neither. What FairCoop is definitely not is an NGO or a company, and certainly also not for profit.

Therefore, FairCoop could be defined with the bulky term “alternative cooperative ecosystem movement” until we find a better terminology.

Balaguer Rasillo (2021, p.6) views FC as a “grassroots organisation,” “a network of cooperatives,” and as “a self-managed financial ecosystem for a transition towards postcapitalism.” In contrast, Dallyn and Frenzel (2021, p. 2) frame FC as “an international movement... seeking to expand and scale up the radical communal anarchist ideals and practices of the Catalan Integral Cooperative (CIC) in Catalonia” and as “a radical/postcapitalist commons alternative.”

As for me, I will study FC as a social movement organisation, and as a network bringing together a grassroots prefigurative community, both online and offline. My focus will be on FC’s online component, as my research question concerns the possibility for online networks to bring about radical collective change.

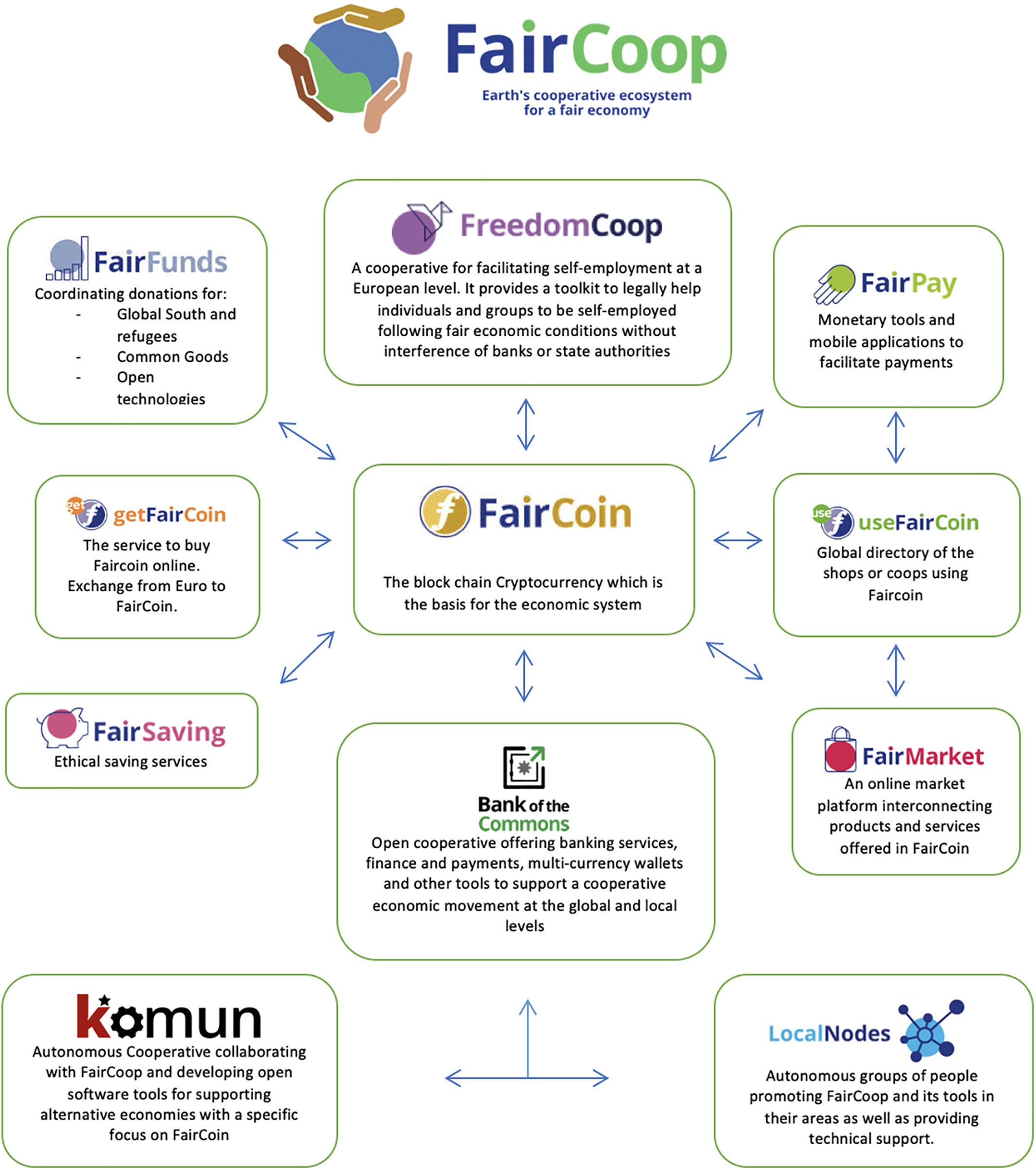

In the hope of further clarifying what FC’s activities were, in terms of radical collective change, I will give an overview of the wide range of projects and activities that were gathered and connected online under the umbrella of FC.

FC’s diverse sub-projects and tools were based around the cryptocurrency FairCoin (Figure 4). These included FreedomCoop, a European-scale cooperative providing individuals with a toolkit enabling self-employment independently of banks or state authorities; Bank of the Commons, a cooperative providing banking services and other financial tools supporting the needs of grassroots economic movements; but also FairMarket, an online marketplace in which goods and services could be bought and sold in faircoins.

Figure 4: The decentralized economic system of FairCoop. Source: Balaguer Rasillo (2021)

An important goal underlying this ecosystem was that of creating a circular economy, defined as “an economy in which the participants are able to find each other and exchange products and services, without the need to go outside of the ecosystem and use Euro or other fiat currency to cover their needs” (FairCoop, no date a). Cooperation, fairness and sustainability were focal points: this economy aimed at creating social change, by encouraging its participants to consider ethical criteria in selecting collaborators and suppliers, and to pay attention to various dimensions of sustainability, including working conditions, human rights, and environmental impacts.

The network also grew to encompass several dozen local nodes, which constituted the grassroots base of FC, in which strong relations of trust were cultivated at the local level. They also aimed to bridge the FC global ecosystem and the multitude of affiliated local projects, initiatives, individuals, and collectives. These nodes were present at one time or another from North and South America to Europe, with a few outliers in Africa, India, and even Syria (FairCoop, no date h; LocalNodesPublishing | board.net, no date). However, it was unclear how many were still active at the time of writing.

During my visits to FairSpot, and reading messages in certain FC Telegram groups, I became aware of tensions in the community. However, as an outsider, I had little awareness of the depth of these tensions. It was only after I began my interviews in earnest that I realised that FC was in a state of crisis. While some interviewees put forth the activities of certain local groups and insisted that some key projects born from this community – most notably, FairCoin – were still going, most of them opined that overall activity was at an all-time low. For some, FC was simply “dormant”; for others, it was a “failed experiment.”

The public minutes of the monthly FC General Assemblies appeared to confirm this state of affairs. These assemblies were a key component of FC global governance, and were normally posted online every month (FairCoop, no date c). But while the minutes were kept and published comprehensively until the end of 2019, only one meeting was documented in 2020, and two in 2021. Furthermore, the attendance of these meetings appeared to have considerably decreased since early 2019, with only four participants attending the latest documented assembly (in March 2021).

This can be related to the notion of absolute doubt, which Dalmau and Dick (1991, p. 7) define as the ultimate stage of breakdown of a project or group:

When absolute doubt is present there is widespread cynicism and despair. The system is barely workable. It may even cease to function, although this is not always the case. An organisation or group can still continue to exist when there is widespread absolute doubt, but will be very ineffective and inefficient. Its members get no rewards for their participation and contribution to common goals. There is widespread breakdown of basic management principles and practices.

This realisation led to important changes in how I approached my research within FC.

My original intention was to help convene and facilitate a participatory research group, composed of various active participants in FC, to explore the kinds of social learning taking place within FC projects. I was hoping that such a group might be willing to look into this question, and that together, we might better understand the dimensions of learning most closely associated with FC’s impact in the world and in participants’ lives. I sympathised with FC’s aims and admired the breadth and sophistication of its projects. My goal was thus to offer my time as a researcher to help bring about collaborative action and understanding that may further the purposes of FC.

However, it soon became obvious that my interviewees didn’t feel they were learning much at all in FC projects any longer, given the community’s decline in energy and activity. To describe this situation using Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayner’s (2020) social learning framework, the social containers – or social learning spaces – that once enabled interactions among participants had mostly become inoperative, and with them, the social learning capability of FC as a social system (Wenger, 2009). This rendered my original research question irrelevant to the people I spoke with.

This led me to sound out what research questions might be more interesting to the FC participants I was in contact with, in keeping with my commitment to carrying out movement-relevant research (Chapter 1), while still remaining faithful to my research’s focus on generating practical insights on how to bring about radical collective change.

Eventually, my conversations led me to settle on the following research questions (RQ) for this chapter:

As I explained (Chapter 3), these research questions led me to adopt a participatory evaluation approach, centred on a convergent interviewing process, and involving fifteen participants.

In the next sections, I will introduce the main answers this research produced to the four research questions above, and discuss their implications. I will conclude on some practical insights that I believe this study brought to the fore, which other social change-makers may wish to consider.

In this section, I present the research findings as they appeared in the final report I shared with all interviewee participants (Chapter 3). The main difference with the final report is that this chapter includes a detailed discussion of the findings in view of the existing literature. I have also moved Section 2 (“A brief timeline of FairCoop”) to Annex 4.1.

I will summarise the opinions on what interviewees considered to be the main issues that affected FC, in terms of:

- Objectives and strategy

- Ways of doing

- Ways of being

The final subsection reviews what the main outcomes have been for interviewees as a result of their participation in FC.

I try to point out areas of agreement and disagreement whenever possible. Quotes from interviewees are highlighted in grey. Interviewees are identified by a number, preceded with a hashtag (#).

Each subsection is followed by a discussion of these findings with regards to the existing scholarly and practitioner literature. For reasons of space, I will limit my discussion to those aspects which feel most salient to me, with regards to movement-relevant learning.

I summarise the key insights drawn from each of these subsections in the conclusion to this chapter.

The interviews revealed a deep strategic and ideological divide within FC, focused on the use of FairCoin. In summary, interviewees spoke of two distinct objectives that were pursued within FC through the use of this cryptocurrency:

Both aspects are mentioned in a statement by founder Enric Duran, published in September 2014, announcing the creation of FC (Duran, 2014) - but it could be argued that the first strategic aspect is more prominent in this announcement. On the FC website mission summary (FairCoop, 2021), these two objectives seem more closely interlinked and on an equal footing.

According to three respondents, a key challenge in FC was that of pursuing these two objectives simultaneously, in spite of the tension between these goals:

“[FC] proposed to launch a cryptocurrency that would be for the [local] circular economy, while at the same time surfing speculative cryptomarkets, without having one of these objectives impact the other.” (#1)

“We wanted for FairCoin to become a kind of exchange, mutual credit, a social money, and that it also be traded in the currency market, with a fluctuating value. These two things were a big big big big mistake, because they were completely incompatible.” (#2)

However, another interviewee argued that both objectives had to go hand in hand: “hacking the crypto market” required a community first building trust in the cryptocurrency used for that purpose.

One respondent mentioned that FC was successful, for a while, at uniting activists from social circles that would rarely mingle ordinarily: “crypto-enthusiasts and social currency supporters” (or, in more familiar terms, “(cypher)punks” and “hippies”). According to this respondent:

“crypto-enthusiasts” were more strongly in favour of FC's avowed strategy of “hacking the speculative markets,” and therefore, were more focused on developing market strategies involving cryptocurrency exchange platforms;

while “social currency supporters ... profoundly despised the crypto-exchanges and the speculation behind cryptos in general,” didn't want FairCoin to be traded online, and disassociated themselves from the “market activism” side of the FC strategy.

According to this same respondent, FC members from local groups, including local producers of goods and services sold on FairMarket, tended to be more supportive of social currencies, and thus were not well attuned to the FC market activism strategy, involving FairCoin being traded in online exchanges – or else they were not well informed about how the value of FairCoin could fluctuate; and this led to misunderstandings and grievances when the market value of FairCoin plummeted, and many local producers found themselves unable to exchange their accumulated faircoins for euros, contrary to what they had been promised by the FC general assembly.

Besides, as mentioned by Dallyn and Frenzen (2021, p.19) based on a FC participant’s testimony:

“at times merchants were brought into the ecosystem on the basis of the promise of FairCoin generating ever increasing returns in Euros on cryptocurrency markets.”

An interviewee agreed that arguments used to invite new merchants into the FC ecosystem were sometimes flawed, and therefore brought in participants who were moved by the wrong incentives:

“I remember visiting a merchant that didn't even have the poster on the shop and didn't make any effort to spend the FairCoin into the economic circle we were creating. So, why was this person in our market? Why it was allowed to participate? It makes no sense. We should have been much more careful when inviting people to participate on the system. They should have been committed people (at least a bit). And yes, this was our fault. I've seen people 'selling' this more as an investment option than a social project.” (#7)

In other words, it seems that the alliance of these two camps was fragile, and built on a lack of shared commitment to (and/or understanding of) the market activism strategy - with the risks it carried. In particular, the risk of FairCoin's assembly price becoming divorced from its market price doesn’t appear to have been widely mentioned when prospective merchants were brought onto FairMarket (see Section 2.1.1 below).

However, while five interviewees expressed broad agreement with this interpretation, five others did not agree, or considered that these different ideological standpoints weren’t at the root of the tensions in FC:

“The main source of conflict was due on one hand to the too high difference between the market price of the FairCoin and the community price at which exchange was promised. There were big disagreements on the topic of the value of the FairCoin and also on the promise of exchange, that was not h[e]ld.” (#3)

“Well there was more of an open debate on how to handle the issue of markets as regards hacking them, but that never ran contrary to the intention of constructing circular economies… [but] given the circumstances, in the end everything got mixed up because everything was interconnected.” (#4)

According to several respondents, a key strategic error was that of making promises (in private and in public) that FC would ensure that faircoins would always be exchangeable for euros at an assembly price which would only ever increase, and never decrease - meaning, in effect, that merchants having been paid in faircoins for their products for example would be able to trade these faircoins for euros. This worked fine at first, while the market value of FairCoin kept rising along with other cryptocurrencies; much less so after the “crypto crash” of early 2018. Now, various participants - including many merchants - were approaching FC asking to trade thousands of faircoins for euros, following the official community rate (i.e. 1.20 euro per FairCoin), which drained the FC coffers.

One interviewee argued that instead of ensuring that merchants would accept FairCoin, through the promise to exchange faircoins to euros, the first step for FC should have been to only allow basic goods and services to be paid for in faircoins, to slowly build up a grassroots circular economy.

Finally, three interviewees also mentioned that certain so-called “bad actors,” with a speculative mindset, purchased faircoins at the cheap market rate and then asked to trade these faircoins for euros at the official community rate, over ten times higher. These interviewees were referring to speculators who weren’t involved in any FC community projects, and suspected that “community members” were doing so too.

In contrast, one respondent said that two local FC-aligned groups making use of faircoins in their country never guaranteed local merchants the possibility to exchange faircoins back to fiat currencies; according to this respondent, this enabled these two groups to avoid the tensions that shook the FC ecosystem as a whole. Another interviewee spoke about similar prudence being exerted within a local group in a different country.

In the words of one interviewee:

A shared vision is extremely important for a cooperative network, as something to latch onto. This was a core challenge. There are all kinds of different personalities in FC - each member may have different visions entering this, and a different understanding of what it means to them. Fighting can occur when it seems that the vision doesn't fit. ... Visions were unaligned. Solidarity and cooperation can mean very different things to different people.” (#5)

On the topic of which another respondent commented:

“It often seems to have depended on who spoke to the merchants as to how their expectations were managed. Some people promised the earth, others almost nothing.” (#10)

In view of the above, it won’t be surprising that all respondents spoke to the critical importance of FairCoin within FC - both in generating energy, excitement and commitment among very different people, especially social change activists (see above), but also as the Achilles’ heel of FC as a project.

"From the beginning, FC was very much focused on FairCoin, unfortunately - so it attracted lots of people into the space. There was a widespread belief in this fairytale: 'We have a cryptocurrency whose value will just keep on increasing.' ... When the value of FairCoin rose from 5 eurocents to 1.2 euros, in 2017, I grew scared - especially given FC's fixed exchange rate from FairCoin to Euros." (#6)

“FC was always dependent on the health of FairCoin... In the beginning, when many people were buying in FairMarket or on the exchanges... Everything was merrymaking and activity (because of the assurances of convertibility to euros, and the promises). Now that the euros are gone, and the markets paralysed... FC seems to be in a coma.” (#1)

Indeed, the fall in value of the FairCoin (together with other cryptocurrencies traded on exchange platforms, such as Bitcoin) in early 2018 seems to have been a major blow to FC: a few months later, Duran announced at the FC Summer Camp that FC coffers were now empty of euros; Komun was officially launched, as a FC affinity group critical of Duran's leadership; conflict erupted, often violently; and by many accounts, most FC activities started unravelling.

Why did this happen? An important factor lies is the design of FairCoin - and in particular, the decision to grant it two independent values:

“Because Bitcoin was on the rise, the project was growing increasingly famous, and the price of FairCoin kept rising together with that of Bitcoin, we decided to grant FairCoin a ‘stable’ value, an exchange value to manage exchanges to fiat currency. This was to make things more secure for the shops and productive projects that participated [in FC], to avoid the volatility of crypto[currencies] that was also impacting FairCoin at that time. We decided on a value of 1 euro, and later 1.20, following market fluctuations of the time.” (#4)

Thus, FairCoin was granted two independent monetary values - one, the official or assembly price, a fixed value that was gradually raised to 1.2 euros (in late 2017), in step with the bullish cryptocurrency trends of the time; and another, the market price, which fluctuated based on the speculation happening in the exchange platform where FairCoin was listed.

But while FairCoin's market price was on a par with the assembly price in late 2017, this market value then crashed to less than a tenth of the official price in early 2018; and because FC guaranteed to merchants on FairMarket and elsewhere the convertibility of faircoins into euros, anyone could turn a profit from buying and reselling faircoins:

“When [the value of FairCoin] started to decrease, decrease, decrease in the market, it was very absurd to offer products and services that could be paid in FairCoin, because anyone could just go 'outside' to the exchange, buy 'cheap' faircoins, and buy things at a higher price inside the community, and profit from this. Therefore, this point for me is what destroyed the community and the project, and the topic of FairCoin was very critical. That was also because there were great piles of faircoins [within the reach] of people who weren't involved in the project, and who were trying to enrich themselves. ...the internal assembly price completely killed the community.” (#2)

This does not imply that anyone asking to trade their faircoins for euros after 2018 were necessarily trying to undermine the project; as mentioned above, it would seem that many merchants were unaware that by doing so they were in effect draining FC of its euros.

In this regard, two interviewees opined that many FC participants - notably merchants accepting FairCoin - lacked the understanding of how markets and economics work, weren’t told clearly about the risks posed by cryptocurrencies traded in exchange markets, or weren’t interested:

“[There was] a lack of knowledge about, and even a rejection of markets and economics by a large segment of the community. This ended up creating a bubble, and later a complete disillusion regarding FairCoin when its [market] price started to decrease. ... An official price should have been accompanied with market strategies, instead of labelling free markets and those moving in them ‘capitalist’ without understanding how they work.” (#9)

A reasonable question to ask, in view of this situation, is: Why wasn’t the assembly price of FairCoin lowered, in line with its decreasing market value?

One interviewee said there were two main reasons for this:

“1) Lots of people thought that this was a decision that didn't make sense for a different number of reasons:

- It was going against some past assembly consensus that the price would just go up.

- It felt as if markets were driving our decisions, and some people thought - I would add, wrongly - that we were supposed to be independent of the markets.

- Some people felt that this would affect negatively the merchants who had been accepting FairCoin at 1.2euros or the people who had bought FairCoin at 1.2eur.

2) Duran didn't want to do it. I wrote 2) to emphasize the role of Duran. As if he would have wanted to do it, I guarantee you that it would have been done.” (#10)

This explanation encapsulates the answers provided by other interviewees, most of whom similarly stressed Duran's key role in preventing the price from being lowered, but also pointed to other reasons for this not happening, in spite of the destructive impact the double-pricing had on FC as a whole:

"Most people wanted to change the [assembly] rate [of FairCoin], except Duran and one or two others. And because of the assembly-based consensus [rule], in which one person can block the decision, we were stuck in the status quo." (#6)

It also appears that FC's “market activist” strategy encountered difficulties due to power asymmetries between the FC project, and the crypto exchanges: one respondent explained that FairCoin was unlisted from the crypto-exchange platform Bittrex due to FC not being a company with a CEO.

“We lost a lot of traction because we didn't fulfil the requirements for being listed on Bittrex - they insisted our 'company' had to have a CEO and we insisted we were not a company and therefore didn't have a CEO - they de-listed us and the price basically went to zero shortly after that. So although we were technically in the right, we didn't realise what a power asymmetry there is between exchanges and tokens (or can be).” (#8)

According to another interviewee, the dependence of FairCoin on such exchanges was a major liability. When FairCoin was unlisted, speculators dumped their faircoins, which spelled “the beginning of the end for FairCoin.”

Unsurprisingly, the crisis brought about by the crash in the market value of FairCoin was described by most respondents as a major source of tensions within the community. One person, involved since early on, mentioned the problem of not getting any value for their many faircoins, due to the impossibility of exchanging them back to euros or spending them anywhere:

"I have loads of FairCoin, since the beginning of the project, I acquired a load of faircoins, and they aren't useful in the least to me right now!" (#2)

Another describes Duran's announcement that FC coffers were empty of euros:

“[During the 2018 FC Summer Camp] all of a sudden Duran announced that we had no funds left, and that those of us who were working [for FC] as well as the merchants would stop receiving euros. It was total chaos. There were many accusations, people blamed each other, many others got involved from outside the project and within, some with their own opinion, others misled by the ‘critics/dissidents’...” (#4)

Following the crash in the value of FairCoin, several innovative proposals were put forth as alternatives or complementary solutions to the ailing FairCoin: for example, FairCredit - a mutual credit system, which would have involved taking FairCoin off exchanges entirely; or the Fairo - a unit of measure for purchasing power, functioning together with FairCoin, and whose value was set to be one thousandth of the basic cost of living in a given region.

However, none of these solutions gained much steam, although the Fairo started to be experimented with locally. One respondent said this was a result of the blockage created by the need to pay off the merchants still waiting to exchange their faircoins into euros.

As of September 2021, some interviewees considered that FairCoin as a project could regain some momentum, as a result of strengthened operational budget thanks to one participant’s investment. Discussions were also ongoing regarding a rebranding of this cryptocurrency. Hurdles still remained concerned technical development, on the one hand; and the need for more widespread support and faith in the project itself.

From the early days of FC, FairCoin was at the heart of the project's activities. This innovative cryptocurrency helped to capture many people's attention, particularly in the era preceding the Bitcoin crash of early 2018.

Chohan (2017) shows how cryptocurrencies emerged from cryptoanarchism - itself an outgrowth of the 1990s Cypherpunk movement - and how these technologies embody in their architecture several central anarchist values (decentralization, egalitarianism and consensus decision-making, self-management and empowerment, freedom and autonomy, cooperative individualism, and addressing local needs). An important caveat to this is that certain aspects in which important cryptocurrencies work do induce centralising and oligarchic trends – for example, how Bitcoin is mined (Willms, 2020). Moreover, according to Husain, Franklin and Roep (2020), while blockchain projects can be considered as “prefigurative” technologies, “embody[ing] the politics and power structures which they are aiming for” (p.383), the political imaginaries that underlie such projects are more closely related to right-wing libertarian politics than to anarchist thinking.

According to the white paper laying out its key characteristics (König et al., 2018), FairCoin is designed to function as a “store of value for the solidarity economy, cooperatives and regional initiatives” (p2) and “is not made for speculators, but for participants on markets to trade real goods and services” (p8). However, the history of this cryptocurrency shows that its troubles largely came from being caught in speculative logics inherent to the global cryptocurrency market, due to the “double pricing” strategy that was pursued. And as the dominant political imaginaries in the cryptocurrency realm appear more in line with free-market, “anarcho-capitalist” mindsets than with the left-wing values advocated by FC and FairCoin (Husain, Franklin and Roep, 2020), it is plausible that the project attracted unwelcome attention from participants with more speculative mindsets – and that the rise in FairCoin’s market value led many FC participants to overlook the speculation that, for a time, raised FairCoin’s profile.

Reflecting on the failure of FairCoin as a tool meant to hack the cryptocurrency markets to build and sustain a post-capitalist commons, Dallyn and Frenzen (2021) argue that such a commons would have needed clearer boundaries and “filtering layers,” “so that capital can be filtered into the commons, while ‘capitalistic value extraction’ [is] prevented from seeping into the internal values and practices of the commons itself” (p14). They argue that this would have helped protect FairCoin from the encroaching values and practices of capital, and avoid diluting FC’s radical anarchist ideals.

In any case, this issue highlights the risks that a prefigurative community will face in trying to simultaneously participate in global financial markets, while building local economy initiatives – particularly if this community has no buffers in place against the fluctuations that affect global financial markets.

This aspect connects directly to the question of FC’s unclear membership, to which I will return below. Interviewees were divided on the importance of FC’s twin strategic orientation, but also on the question of whether FC suffered, strategically, from disagreements between two broad groups of participants – whom one participant referred to as “crypto-enthusiasts” and “social currency supporters.” Some considered the FC strategy as self-contradicting, and described an uneasy relationship between these two broad cultural groups, while others did not consider this an issue.

The effect of boundary-spanning in SMOs, be it relative to issue and identity, organization, or tactics, is a topic of ongoing debate among social movement scholars (Wang, Piazza and Soule, 2018). For example, Olzak and Johnson (2018) make the case that a more specialised (or “single-issue”) SMO will:

- be recognised as a more coherent entity, which facilitates outsiders’ interpretations of its activities and thus secure better legitimacy;

- more easily attract new adherents who are truly committed to a particular cause, and maintain higher loyalty among its supporters;

- have a lower chance of dissolution due to having fewer cleavages – over divergent interests, politics, or loyalties - that may promote internal conflict;

- more easily acquire organisational capital (including members’ loyalty, commitment, and technical skills, along with organizational finances, internal solidarity, and external reputation).

These authors’ longitudinal study of multiple environmental SMOs revealed that those which adopted a relatively broad “issue frame” (spanning dissimilar issue areas) did not last as long as specialised SMOs. These findings, and particularly their emphasis on the issue of cleavages as a source of conflict, appear relevant to the case of FC.

However, other authors argue to the contrary. For example, Heaney and Rojas (2014) show that SMOs – for example, those involved in anti-war protest organising – often gain substantial advantages from forming hybrid identities that blend established organisational categories. Such organisations may act as important brokers between movements; help new supporters connect with a movement in ways that feel suit intersectional identities; and by helping to build inter-movement networks.

These findings can be usefully compared to the results of Leach’s (2009) investigation of the German Autonomen movement. She concludes that the longevity of this movement over many decades, and its ability to sustain a collectivist-democratic structure, is in fact largely due to deep contradictions running through its ideology and identity. This permanent tension has been a source of an ongoing dialectical process of negotiation and reflection, which has paradoxically strengthened the movement and prevented it from becoming dogmatic or from dissolving completely.

FC can arguably be considered to have spanned at least two broad sets of issues and identities, along with two corresponding different tactical repertoires. Whether this was a strength or a liability overall remains unclear and requires further investigation. In any case, it appears that more could have been done to ensure all FC participants were aware of the implications of strategic decisions that were made – for example, in making FairCoin vulnerable to the fluctuations of speculative financial markets.

What are some important lessons that can be drawn from FC's trajectory, in terms of governance, tools, and other strategic decisions?

Four respondents pointed to the unacknowledged power dynamics that operated within FC:

“The FC origin story.... relied heavily on [Duran,] ended up giving him a de facto power within the group, which he would use when necessary and deny existed when it suited him, for example when people made him responsible for things which had gone wrong (sometimes wrongly, sometimes with good reason), he would say 'it's not about me, this is a decentralised cooperative' or similar. But then he also frequently used the power to force through decisions he wanted, and block others he didn't, all the while claiming there was no leader. Of course this requires others to also give up their own power.” (#8)

Two respondents considered that the situation in FC was a classic case of the “tyranny of structurelessness.” While FC aspired to be a non-hierarchical and decentralised social structure, covert hierarchical patterns emerged in practice - for example, when deciding who to trust with passwords to important software infrastructure. And these patterns didn't only empower Duran:

"Not all the power was concentrated in Duran, other community members' voices had weight, and towards the later stages often more weight than that of Duran, because he had been somewhat discredited by how things had played out." (#8)

This respondent blamed these covert power structures for much of the conflicts which happened. Indeed, members of the faction opposing Duran (see below) repeatedly mentioned Duran's central role in FC, and what they considered a lack of transparency, as a key incentive for them to form their dissident affinity group.

Corroborating elements regarding the lack of transparency in decision-making include a detailed FC dossier introducing various aspects of FC governance (FairCoop, 2018). While it states that decision-making in FC takes place through general assemblies, it doesn't mention actual rules of engagement within these assemblies. Similarly, on the FC Wiki, sections on “Decisions” and “Assemblies” were left empty (FairCoop, no date c) .

In practice, as two respondents have confirmed, major decisions could only be taken in the monthly FC general assemblies following strict principles of consensus, which made it impossible to adopt a motion if at least one person opposed it:

“A key mistake... was to use Telegram-based assemblies as a decision-making process. But on top of this, there was also the use of a particular notion of consensus, in which one couldn’t change any previous decision as long as a single person was against it. This suited Duran very well, as sometimes he was the only one who refused to reverse any old decision he took himself, even though other people agreed on reversing it. ... Consensus only concerned everyone participating in a given assembly - in English, on Telegram, at a given date and time. So you could be faced with decisions taken by a few people that were then impossible to change.” (#9)

Three respondents also mentioned that because there was no official membership system in place, it was problematic to know whether “everyone was there” (or at least, whether certain stakeholder groups were represented) during an assembly, which could affect the legitimacy of any decision that was taken. And the fact that reversing decisions was so difficult - as even a single person could block such a motion - made legitimacy an even thornier issue.

For example, I asked one interviewee whether the decision to adopt and develop OCP, one of the main sources of conflict in FC (see below), was done democratically. They replied:

“Yes and No. Yes because we have discussed it in different assemblies and the consensus was to support it. No because the consensus was done by a small group of people in Telegram chat groups and Etherpads. The support of a major part of community was not really given but more or less supposed.” (#13)

An interviewee opined that no decision to use OCP was ever taken in any FC general assembly.

And while Telegram-based assemblies allowed for non-participants to read the text messages shared for the occasion (see below), in practice some found this discouraging due to the sheer volume of text messages to catch up with. One interviewee also pointed to the lack of adequate and inclusive methods of coordination and decision-making, which could have ensured that different voices be heard and respected.

Once tensions came to a head, in the wake of the collapse of FairCoin's market value, conflict erupted in assemblies and decision-making grew all the more arduous:

“Decisions were very difficult to make. Anyone could oppose the decisions, so there was a lot of fighting; as a result, people who might say no would abstain not to be attacked. Having anonymous voting would have helped.” (#5)

Two interviewees spoke more generally of the problem of leadership in groups that are supposed to be horizontal and avoiding hierarchy:

“The problem with flat structures is that everyone is waiting for someone to take the lead, and then when you do take the lead people feel think you're being an elitist, disregarding the collective. So there is a general tendency to just hang around, not feeling ok to take any leadership.... [In FC] it was always difficult to figure out how to make sure the structure could be both flat and functional.” (#3)

“[Duran's] position has been influential in everything, because he was the focus of everything. And he is the one who, in the final analysis, takes all decisions and manages the funds.” (#4)

Nearly all interviewees spoke about the key importance of Duran's involvement in FC - both as the leading figure who initiated the whole project, but also as someone bearing a heavy responsibility in the troubles that befell FC, which caused the decrease of activity in the project overall.

“The origin story of Enric's 'action' was very helpful in getting us new members, but it had a downside: too much power invested in one person, in a community which was supposedly non-hierarchical.” (#8)

“Basically, Enric has treated FC as his own thing/project/company. And I understand why. He put so much work, enthusiasm, and even money into it. I think that probably FC wouldn't have ever existed if it wasn't because of him. Yet, if you wanna behave as a boss/owner, then you should made that clear from the beginning. He launched some sort of very ambitious, decentralized, radical movement, close to anarchist thought. He surrounded himself by these radical people. He made them think that they were all part of a radical team. But when things got worse he made it clear that he was the one in charge because he was the only one who had access to the money. He had a paternalistic and patronizing attitude towards the whole ecosystem, and that created lots of human problems. Because some people kept seeing him as some kind of leader.” (#10)

Criticisms concerned various aspects of Duran's action and leadership style, especially:

- An inability to admit mistakes and take responsibility;

- Denying the existence or seriousness of the problems affecting the community; and

- An unwillingness or inability to listen to others or delegate.

Despite widespread criticism, two respondents did make a point of mentioning they felt it was unfair to blame all of FC's troubles on Duran:

“I'm against that, that all the blame goes to one person and everybody is blaming Enric, and it's Enric's fault? No, we are sharing this responsibility, we are not children... it's always blaming, and it's not me, I'm not capable to reflect or to take over my own responsibility... all of those people I love, they're amazing people, extraordinary individuals. But we as a group, as a movement as a community, we failed together. It's not like individual responsibility.” (#12)

Here, I will focus on three particular criticisms that were recurrent in my interviews, and which have to do with the governance of FC. The first was widely shared; interviewees were more divided regarding the second and the third.

Eight interviewees pointed out that Duran was the sole manager of the “common funds” in FC, which they described as being ultimately controlled by Duran alone from a bank account only he had access to; and that he never reported back on his management of these funds.

“There wasn't much transparency on how many euros were 'in the box'. Everything was in Enric's hands, and when we asked him about this, he kept making excuses, saying he didn't have time to check. ... While FC was supposed to be built on principles of transparency, decentralisation, and openness, in practice the transparency and decentralisation aspects weren't so strong.” (#2)

This concentration of the project’s finances into Duran's hands seems to have occurred largely as a result of his raising these funds to initiate this project. Duran then retained a large degree of control over the financial infrastructure of FC:

“In a way, 'the common funds' were his funds. Because after all, he donated millions of faircoins to FC, and all the euros that FC had amassed were thanks to the sells of faircoins (via the official platform) to 'anonymous' people. But again, he embellished the whole thing as if 'his funds' were 'common funds' and he was just a responsible manager of 'the commons'.” (#10)

One interviewee said that Duran also raised funds with private investors who had to remain anonymous, and that because he was the only person bringing euros into FC, he was made into “the leader” and had to shoulder extra responsibility. Local groups could have helped to raise their own funding, which didn’t happen.

As a result of his control over FC finances, on top of his notoriety, Duran was able to wield considerable political power within FC. Three interviewees stressed the problematic connection between Duran's deep involvement in FC finances, and his lack of transparency in doing so, and how that affected people’s status and treatment within the community.

One of them argued that although Duran couldn’t choose on his own who should be doing what, whenever he proposed a candidate for a certain role, his candidate was usually endorsed by the assembly. The same person also regretted that people with a closer connection to Duran had priority if they wanted to convert into euros any faircoins they earned while working for FairCoop – while other people had to wait. In this way, Duran’s control over these conversion operations was another source of power.

One respondent nuanced this statement, pointing to how Duran had to start somewhere as he started building FC from scratch, and thus naturally turned to close friends and allies, along with others he found had the right skills to play a certain role. They also opined that responsibility for certain roles was also taken on as a result of nominations put forth by other members of FC.

Three respondents charged that Duran's disproportionate influence in FC extended to the realm of technical decisions regarding FC software - despite Duran not having expert technical knowledge himself. One person argued that Duran tended to entrust close friends and allies with key technical roles, and implied that opinions from the rest of the community had less weight in this matter.

This is a significant charge, given that the question of tools to use has been a major bone of contention within FC (see below).

According to three respondents, criticisms such as those mentioned above, and the controversy that grew as a result - culminating in the creation of a dissident faction - led to an important loss of trust and credibility for Duran as time went by, to the extent that other participants ultimately even grew more influential than him.

“The topic of technical issues in FC, too, was a black hole, quite a powerful one, which created a lot of division.” (#2)

In the summer of 2015, during the first FC Camp in Greece, participants began to use the messaging software Telegram to communicate. It gradually became the primary communication and organisation tool for all FC activity outside of local groups. Each FC project or area of activity soon had its dedicated Telegram group for participants to coordinate their activities.

Importantly, while Telegram allows online calls, as well as recorded voice messages, the norm within FC was to engage with this medium nearly exclusively through text messages - even in circumstances that would seem more suited to voice or video calls, such as the FC general assemblies.

An interviewee pointed out that text messages were useful, during assemblies, as meeting minutes for those who couldn’t attend. Another stressed how the convenience of Telegram allowed the rapid expansion of FC groups and the organic burgeoning of various initiatives and projects. However, the limitations of this medium were pointed out by six interviewees - particularly the difficulty of keeping pace with rapid-fire conversations happening over chat during assemblies.

“There's a limit [to what] you can really handle in an online assembly and a chat. Because it just takes too long. It's confusing. Nobody, not everybody can put in their own opinion, and then just it explodes in terms of time, and in terms of chat messages...” (#6)

Text-based interactions were also blamed for hampering empathy and failing to solve conflict. For example, respondents pointed out the difficulty of sensing other people’s emotions, or understanding their sense of humour.

Another interviewee mentioned having encouraged others within FC to use video calls, in order to overcome conflicts and misunderstandings, but to no avail: the habit of using typed communication in Telegram had become too ingrained within FC spaces. Another person chalked this up to the activist culture of anonymity that characterised these spaces.

More generally, three respondents linked the conflict and lack of trust that spread in FC to the online nature of the community, and stressed that physical meetups like the annual summer camps were much more peaceful:

“We hurt one another so much online. Except when we could meet physically, be together and that was the coolest time, because we were all there, we could see each other’s faces, discuss, debate, think together… that was the nice stuff. But everything online, the chats, the criticisms, all this largely failed.” (#2)

Another way in which tools proved to be problematic in FC has to do with the adoption of OCP, an enterprise resource planner (along with the associated methodology OCW), which generated much controversy. This software was meant to keep track of flows of value within FC, and to reward people for their contributions via mutual checks on each other’s work.

All interviewees identifying with Faction 1 (see below) mentioned this topic as a key reason for their discontent - and agreed on three main criticisms:

- OCP was not adopted democratically, but due to the lobbying exerted by a small group of people including Duran;

- too much money was spent on it;

- OCP was not useful, or not useful enough.

Interviewees who didn’t identify with Faction 1 had different opinions as regards these criticisms:

- While some believed there was wide agreement to adopt this tool - and stressed that there was no opposition to it when it was proposed for adoption during the FC summer camp in 2017 - others said that the openness of FC assemblies, and the way in which decisions were taken in such assemblies, always made it possible to question the legitimacy of any decision;

- One interviewee was unsure whether OCP had been democratically chosen to be used in FC, but was certain that it hadn’t been chosen by an assembly for use in Bank of the Commons (BotC), a FC-related project, although much investment into the development of the tool had come from BotC.

A respondent, who identified with Faction 1, mentioned that this tool was initially proposed for billing in one of the projects born within FC, but that it was never formally adopted for use in FC or BotC.

Three interviewees defended the adoption and use of OCP and OCW, and five others said that it could have been useful for FC as a value network tool, although it was still unfinished software, and suffered from implementation issues:

“It was partially useful for organising the work we had, yes, but not ready. The process itself, like validating the work of each other was to[o] idealistic IMO, which also created ten[s]ion between workers in FC and was one puzzle piece to the whole d[i]lemma.” (#6)

Two respondents mentioned that OCP was introduced in a way that made it hard to accept and understand by non-technicians in FC; two other interviewees concurred that a lack of organisational capacity or proper planning was also to blame.

Finally, two interviewees also mentioned that the use of OCP was a factor of conflict due to the difficulty of keeping track of who was actually doing productive work for the community in exchange for payment:

“When some of us started getting money from the OCP, some people started to make tasks and not doing anything... Which led to suspicion. Enric said ‘you work 5 hours as a volunteer, and then you can get paid’. Therefore, money became a problem. People attacked one another.” (#7)

I will now turn to a final aspect of the “ways of doing” that seems to have been problematic: the issue of FC membership.

FC may have suffered from a fragile alignment between those participants who were intent on “hacking the markets” to bring liquidity into the ecosystem, and those who were more focused on grassroots economy-building and community currencies (see above).

Beyond this divergence of opinion, six respondents also mentioned another important issue in their eyes: that the main FC Telegram groups (e.g. the General Assemblies group) were open to any newcomer, as links to join these groups were displayed on the FC website. This openness enabled their rapid growth, but was also a source of distraction, as conversations were interrupted by trolls, or newcomers unaware of how FC worked.

Besides these disturbances, some interviewees linked the issue of open membership to that of a lack of foundational shared norms or objectives within the network.

“Faircoop was maybe too open and did not manage to make clear the necessity for a culture shift towards decentralisation and self empowerment.” (#3)

According to one, this created confusion due to the diversity of actors involved, and allowed the angriest, loudest voices to dominate conversations.

Two respondents said that the openness of FC meant that new members would keep joining projects at different points in time, without benefiting from the organisational memory needed to make sense of what was happening - and thus feeling a disconnect with more experienced participants.

In the words of one interviewee, the open nature of FC groups meant that they couldn’t function effectively as true commons, following Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) design principles: membership boundaries should have been clearer. The same respondent spoke to social cleavage in FC, between more “middle-class” participants and “anarchist/squatters,” in terms of financial needs and expectations, as well as in exposure to burnout (see below).

Another respondent also mentioned how the very growth of the FC ecosystem led to an increase in the workload and the processes needed to manage that expansion.

Most interviewees charged that while FC was a supposedly non-hierarchical and decentralised project and network, unacknowledged power dynamics were at play. These patterns gave extra weight to long-term FC participants, and in particular Duran, to the detriment of others. This situation, which many experienced as disempowering, was made worse by the way consensus was used in the project, preventing any assembly decision from being passed (including motions to reverse previous decisions) as long as at least one person blocked it. In this regard, delegating certain decisions, for example on technical matters, to sub-groups who would then be held accountable by the assembly, might have been a more productive design.

Duran's role has been described as instrumental, both in launching FC and securing energy and commitment around it, but also in failing to make its governance more genuinely participatory.

The question of FC’s governance brings us to focus on the central aspect that characterise it as a prefigurative project: the use of participatory democracy, as “an organizational form in which decision making is decentralized, nonhierarchical, and consensus oriented” (Polletta, 2014, p. 1). Indeed, the Integral Revolution manifesto makes it clear that FC aimed at bringing into being a society marked by values of radical equality, freedom, and community that commonly justify the use of this organizational form, following Breines’s characterisation (Breines, 1989).

Maeckelbergh (2009) argues that the practice of prefiguration and the development of participatory democracy have been intricately linked historically, particularly in the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and that while the meaning of the term has evolved, it is most commonly conflated today with the practice of consensus-making (pp.14-15). She also contends that prefigurative politics are closely associated with anarchist praxis, particularly “when the means and ends being used/enacted… are attempting to be as non-hierarchical as possible”, and cites anarchists during the Spanish civil war as one of the most famous examples of prefiguration (pp.86-87).

In her ethnography of decision-making processes in the Global Justice Movement, she investigates the practice of horizontality as a key prefigurative orientation: “[It] is a term used by movement actors to refer to less hierarchical, networked relationships of decision-making and organising structures that actively attempt to limit power inequalities” (p.69). She describes horizontality both as “a decentralised network structure that produces non-hierarchical relationships between the various nodes (people, groups, ideas) of a network” (p.109) and as an attitude and ethos – allowing for oppressive forms of power (power-as-domination, or power-over) to be transformed. This is accomplished through the use of consensus, as “the only legitimate decision-making method for limiting hierarchy and increasing horizontality” (p.122). This allows an organization to avoid bureaucratic decision-making structures, which are seen as concentrating power and thus hierarchy. From interviewees’ testimonies, it appears that horizontality was an important practice within the context of FC.

Following Graeber (2007, p. 341), consensus can be defined as

a process of compromise and synthesis meant to produce decisions that no one finds so violently objectionable that they are not willing to at least assent…. Most forms of consensus include a variety of graded forms of disagreement. The point is to ensure that no one walks away feeling that their views have been totally ignored and, therefore, that even those who think the group came to a bad decision are willing to offer their passive acquiescence.

However, as pointed out above, it appears that in FC, little was done to allow for the expression of “graded forms of disagreement” – as many decisions appear to have been blocked by individuals repeatedly, thus making it impossible to resolve certain critical situations, such as FairCoin’s double pricing issue. I return to this issue below.

According to Polletta (2014), many social movement scholars view participatory democracies as fragile, and raise issues of:

- inefficiency;

- inequity; and

- irresolvable disagreements in participants’ interests.

This raises the question of the extent to which the practice of horizontality, and more widely, participatory democracy, might have been a stumbling block for FC. I will explore each of the three recurring criticisms of this form of decision-making in the light of interviewees’ testimonies.

1. Was FC considered inefficient?

Scholars often view participatory democracy as lacking efficiency due to the time spent in consensus-making decisions, problems of coordination from decentralised administration, and minimal labour division sacrificing the benefits of expertise (Breines, 1989; Polletta, 2002, 2014). Studies of participatory-democratic groups have surfaced frequent tensions between “pragmatists,” calling for more centralised and hierarchical organisational structure, and “purists,” refusing such reforms (e.g. Polletta, 2002). Within the context of the Global Justice Movement, people embracing such orientations were respectively referred to as “verticals” and “horizontals” (Juris, 2008; Maeckelbergh, 2009). These tensions tend to lead either to the bureaucratisation, or to the collapse of the group.

While some FC interviewees did refer to lengthy assemblies, the efficiency of decision-making processes was not a recurring theme in my interviews. Besides, efficiency did not seem to be an issue directly at play in mentions of conflict within the community; but it is likely that it was, indirectly, through the controversial introduction of the enterprise resource planner software OCP. Interviewees mostly discussed the tool’s usefulness (or lack thereof) with regards to monitoring and rewarding contributions on behalf of network participants (see next section). However, increased efficiency in the administration of decentralised tasks in FC appears to have been part of the rationale for using it, from its proponents’ point of view.

In any case, the lack of delegation of decision-making power to task forces within FC, and the possibility for individuals to repeatedly block any decision within the assembly, appear to have prevented many important decisions to be taken efficiently.

2. Was FC considered inequitable?

Two widely-discussed phenomena tend to be associated, in the scholarly literature, with inequity in participatory democracies: the “iron law of oligarchy,” and the “tyranny of structurelessness.” The former was theorised by Michels (1915) as referring to oligarchic structures “inevitably” (p.27) emerging within any organisation, no matter how democratic. As for the latter, Freeman (1972) describes it as the free rule of informal cliques within democratic groups seeking to avoid bureaucracy and other formal structures of authority.

To what extent do interviewees’ testimonies imply that either of these phenomena was at play? I will examine each possibility in turn.

Oligarchy

As regards the “iron law of oligarchy,” first of all, it is important to stress that while a number of empirical studies have found it at play in supposedly democratic groups (e.g. Hernandez, 2006; Tolbert and Hiatt, 2009), others (e.g. Leach, 2009; Polletta, 2014; Diefenbach, 2019) have also shown that it is far from being the kind of “sociological law of universal validity” proposed by Michels (1915, p. 210).

Leach (2005) defines oligarchy as “a concentration of entrenched illegitimate authority and/or influence in the hands of a minority, such that de facto what that minority wants is generally what comes to pass, even when it goes against the wishes (whether actively or passively expressed) of the majority” (p.329). Following this definition, to show that such a phenomenon may be at play, one needs to show that:

- the group in question has a democratic structure;

- a minority wields a disproportionate and illegitimate influence in or on the group;

- the majority of participants in some way resisted that power; and

- the minority tend to overcome this resistance on issues that it feels are important.

Regarding the first point, Leach refers to a democratic structure as one including, at the very least, “structural mechanisms that place ultimate governing authority in the hands of the organization’s membership—either through direct participation in all important decisions or indirectly through the election of representatives—as well as structural protections for the minority and checks on the power of elected representatives, where they exist” (p.316). In terms of the global governance of FC, which is what I am focusing on, the FC Wiki page describing processes in use stresses the critical role of open global assemblies, but is noticeably incomplete as regards decision-making (FairCoop, no date c). Besides, local groups federated through the FC network were expected to be autonomous and self-organising (FairCoop, no date g).

All research participants mentioned the use of consensus in the general assemblies as the primary decision-making process, which implies that ultimate governing authority was indeed placed in the hands of the membership, and that there were no elections of representatives. I found no mention in FC documents of structural protections in place for the minority – but considering the power granted to any assembly participant to block any decision, and the avoidance of voting in favour of unanimous consensus, minority opinions were indeed protected. Referring to the Global Justice Movement, Maeckelbergh (2009, p. 162) writes: “Consensus is one of the ways movement actors try to continuously create equality. In most collective spaces of this movement voting is considered an automatic violation of equality. Voting violates equality because it silences minority voices.”

So I will assume that FC had a participatory democratic structure based on the use of consensus decision-making.

In terms of the second item on Leach’s list, does it appear that a minority was wielding a disproportionate and illegitimate influence within FC? Most interviewees charged that Duran wielded considerable influence, especially due to his control over FC finances. Some also considered that this influence was exerted through friends in influential roles, and/or through technical decisions that were made. Whether or not this influence was “illegitimate” would depend on FC participants’ perception of Duran’s right to this influence, and the extent to which he used means considered inappropriate – following prevalent group norms – to affect decisions (Leach, 2005, pp. 326–7). Again, most interviewees expressed disapproval of how Duran wielded his influence, although some did justify this influence on the ground of the risks he took, his instrumental role in creating FC, and the funds he channelled into the network.

Did most FC participants actively resist this influence? This is difficult to ascertain. While most interviewees expressed disapproval of it, it is unclear how many took a stand against it, and how – besides members of the Komun affinity group, which were most critical of FC governance. As a result, it is equally unclear whether there was a pattern of the minority being able to overcome resistance on issues it felt were important. Some interviewees did mention that Duran’s influence and credibility eventually waned within FC, which could indicate that resistance became stronger with time.

Therefore, while there are signs that an oligarchic pattern of influence was at play within FC for some research participants, further investigation would be needed to ascertain the extent to which this impression was shared.

Structurelessness

I will now turn to the other commonly mentioned reason for inequity developing within participatory democracies – the “tyranny of structurelessness.” Freeman (1972) argues that:

There is no such thing as a structureless group… [the idea of structurelessness] becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others. This hegemony can be so easily established because the idea of ‘structurelessness’ does not prevent the formation of informal structures, only formal ones…. As long as the structure of the group is informal, the rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few and awareness of power is limited to those who know the rules. Those who do not know the rules and are not chosen for initiation must remain in confusion, or suffer from paranoid delusions that something is happening of which they are not quite aware. (p.152)

This concept is critiqued by Leach (2013), who points out that many consensus-based groups have learned from the failures of the 1960s and 70s feminist groups that Freeman analysed. She argues that contemporary participatory democratic groups are less eager to avoid structure or division of labour altogether, and rather trying to avoid formal hierarchy and systematic inequalities of power. As a result, the primary question to examine should be “what kind of structure to have that will maximize participation and prevent anyone from dominating the group” (p.183 – emphasis in the original). She also shows that having too much structure can be just as detrimental to a group, as in the case of Occupy Wall Street meetings that felt alienating to marginal or oppositional groups, and that fostering an egalitarian culture is at least as critical than having the right structures in place to prevent informal elites from dominating a group. This corresponds to Maeckelbergh’s characterisation of horizontality as comprising both a structure, and an attitude or ethos (2009, p. 109).

Nonetheless, it is notable that two interviewees spontaneously mentioned the “tyranny of structurelessness” being at play in FC, as a result of informal power dynamics and a corresponding lack of accountability. In this regard, as I mentioned above, I find it striking that while there are traces of FC participants exploring how to better shape democratic processes within the network, including through the use of better tools (FairCoop, no date e), public documents presenting FC governance are noticeably lacking in details on any formal processes. Of course, this does not mean such tacit processes did not exist. But I feel tempted to agree with these two participants on their assessment – especially since the “conflictual culture” that Maeckelbergh (2009) and Leach (2009, 2013) highlight as a key element of consensus-driven groups’ ability to enact horizontality (by viewing disagreements and critical discussions of power dynamics as a way to preserve diversity and equality) did not appear to be encouraged in FC. Indeed, although a group of participants did become vocal critics of FC governance, power dynamics do not seem to have been altered substantively as a result of their complaints. I will return to the issue of conflict in the next sections.

Besides, according to Gerbaudo (2012), who investigated the new forms of protest that emerged in the first decade of the twenty-first century, structurelessness is “an astute way of side-stepping the question of leadership, and allows the de facto leaders to remain unaccountable because invisible” (p.25). So the question of structure – or lack thereof – is also connected to issues of leadership, which I discuss below.

Another important aspect of the political culture associated with the use of consensus has to do with the use of the veto (or “block”). In theory, the practice of consensus enables a group to balance the inequalities of power that characterise individual participation in the process: everyone has absolute power to block a decision in a meeting they are part of. However, the underpinning logic is that a block should only be used when a decision is considered to violate one’s most fundamental interests:

The individual actor is expected to put the interests of the group above their own, except when her basic values or principles would be violated by the decision being reached. In such a case, the group is expected to respect the individual, not the other way around… When a block is used (in large groups), it requires that the whole group take seriously the individual’s concern and try to understand it in order to either rework the proposal to resolve the concern (which is what usually happens) or to find a satisfactory way out for the person blocking. (Maeckelbergh, 2009, p.165).

Several interviewees pointed out that the disproportionate influence of certain FC participants was manifested by these participants repeatedly blocking certain proposals they disagreed with. Reasonable questions to ask, in this context, would be: Was the right to block a proposal in FC generally considered as an ultimate recourse, or did it become normalised as a way to obstruct any process going against one’s wishes and interests? And were participants able to challenge a block they found was not justified, or to help the blocker find grounds for compromise with others? Graeber (2013, p. 109) mentions such processes being commonly used within the Occupy movement. As for Haug (2015, p. 30), he stresses the need for “formalizing the consensus building process in a way that ensures that concerns about the emerging decision are heard and addressed at an early stage so that nobody will be forced to resort to blocking as the ultimate means to be heard.”

As the right to block a decision is such a central aspect of the praxis of consensus-based groups, it appears worthy of further exploration in the case of FC.

3. Were there irreconcilable interests within FC?

The third commonly perceived weakness of participatory democracies is that consensus processes provide no means for adjudicating fundamental conflicts of interest (Polletta, 2002, 2014). This can create a stalemate, which may devolve into an organisational crisis.

I explored the question of possibly diverging goals and objectives in FC in the previous section (“Strategy and objectives”). Some interviewees did consider there might have been contradictory interests within the network as a result of FC’s twin strategic orientation, towards hacking the global financial markets and building a grassroots economic system. They described how the problematic double pricing of FairCoin – particularly following Bitcoin’s 2018 market crash – led to a situation of irreconcilable interests: on the one hand, merchants who sold products in FairCoin were not able to exchange these faircoins into euros; and on the other, several FC participants refused to lower FairCoin’s official (“assembly”) price. As a result, as one interviewee put it, FC became “stuck in the status quo,” and the consequences for the whole community were disastrous.

Therefore, it does appear that FC’s decision-making processes were unable to resolve the FairCoin double pricing situation, and thus point to a critical governance failure.

In summary, interviewees’ testimonies do highlight certain weaknesses of participatory democratic processes that are widely discussed in the literature on social movements. At the very least, it appears safe to state that there were signs of oligarchy and informal power structures, contradicting FC’s democratic ethos; as well as irresolvable disagreements between various stakeholders, particularly with regards to financial questions and FairCoin.

When I asked them about FC’s governance issues, some participants said that an important reason for the inequities that they observed was that few people were actually willing to take on leadership roles within the network – which concentrated influence in the hands of the most active participants. I will briefly discuss what the literature on leadership in self-styled “leaderless” groups may tell us about this situation.