- Introduction: Setting the scene

- Tools of emancipation, or tools of alienation?

- My research approach

- Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

- Introducing the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF)

- The Diversity & Decolonising Circle

- The Research Team

- The DAF Landscape: Cultivating relationality

- Considering DAF from a decolonial perspective

- Radical collective change

Radical Collective Change

(a summary)

In the previous summaries, I discussed various aspects of the two case studies that I examined in this research - FairCoop and the Deep Adaptation Forum. I pointed out some interesting things that can be learned from each of them, with regards to their successes and shortcomings; and forms of social learning that appear to have been taking place within these online communities.

However, astute readers may have noticed that so far, I have refrained from stating whether I think that radical collective change has taken place through FC or DAF. Rather, what I did was mostly take the perspective of participants in these communities, and consider whether they found that interesting changes took place for them (or around them), thanks to these networks.

But what do I think? Has radical collective change been taking place?

This is necessarily a subjective assessment: deciding whether the world has "radically" changed depends, for example, on how one sees the world; on the relations of causality between the state of this world at a certain time, and factors influencing it; and even on the forms of change that one may desire to see!

So to answer this question, I will draw from my embodied experience of being and interacting with the two communities of FC and DAF, and the "first-person action research" that took place for me as I took notes in my journal about what I was experiencing. This will lead me to consider how the way I think and feel about radical collective change and prefiguration has evolved over the course of this research; what I have been unlearning – if anything – during this process; and how this came about.

This is a summary of Chapter 6 (with some bits from the Conclusion, which I invite you to go check out for more details.

TL;DR

- For me, a prefigurative (online or offline) project will have the potential to bring about radical collective change if two main conditions are in place: 1. this project forms part of a mycelium of initiatives, taking a decolonial approach to address the 4 constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality; and 2. a community of critical discernment is cultivated to nurture this mycelium.

- Assessing whether this is taking place requires one to step away from modern-colonial frameworks of analysis, which are based on separation and dualisms - and embrace a decolonial approach, that is fundamentally about relationships and in service to life.

- My feeling-understanding (senti-pensamiento) on the topic of radical collective change has evolved through an unfinished, never-ending process of (un)learning - in other words, a process of deconstructing and critically examining knowledge and understanding, as well as affective, somatic and relational states, particularly those that come from dominant cultures and privilege.

- Composting the cultural "shit" that has accumulated within each of us, preventing deep change from happening, requires facing the 4 constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality - i.e. the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm; the denial of the limits of the planet and of the unsustainability of modernity-coloniality; the denial of entanglement; and the denial of the magnitude and complexity of the problems we need to face together.

- The D&D Circle was a social learning space in which my co-participants and I faced into, and attempted to compost, the denial of systemic harm and injustice.

- Psychedelic experiences have helped me to face the denial of entanglement in which my culture of separation has raised me - as it privileges the use of a symbolic-categorical compass, obsessed with knowledge, meaning-making, and control.

- I found that DAF provided groups and spaces that looked into each of the 4 denials of modernity-coloniality - so there were potential factors of radical collective change in DAF. However, few participants took part regularly in these spaces, and integrated these different practices together. In particular, not all groups centred the awareness of systemic injustice and historical harm.

- In FC, there seemed to be little emphasis on changing participants' ways of being, on relationality, and on facing the 4 denials of modernity-coloniality. So there was little potential for radical collective change.

- In order for this potential to emerge, and for this composting to happen, there is a need for community structures and processes fostering belonging and critical discernment. These include: trust and belonging; space for generative conflict; emergent leadership; and the cultivation of critical discernment.

- These elements did not seem to be very present in FC. Some were more present than others in DAF.

- As no initiatives (in FC or DAF) addressed all 4 denials of modernity, no actual radical collective change seems to have taken place through either of these networks, according to my definition.

1. (Un)learning to create change

As I mentioned before, I found that a decolonial approach invited me to become more aware of how my social position (including my gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, education level, nationality, etc.) has influenced my approach to understanding radical change - among many other things. Besides being a PhD student, I am White, Western, cis-gendered, heterosexual, male, able-bodied, and a quasi-native English speaker, which are some elements granting me much power and privilege, and conditioning my perspective.

My approach to and definition of radical collective change evolved as I grew more and more conscious of how my understanding was conditioned by such factors. In the early stages of my research, my (pragmatic) approach was that there are certain forms of social learning that are universally useful to create positive change in the world (and what was needed was to discover these forms of learning, and the ways of spreading them); but as I grew more and more interested in the decolonial critique, I started to understand that unlearning was at least as important as social learning.

One way of defining unlearning is as a process of deconstructing and critically examining knowledge and understanding, as well as affective, somatic and relational states, particularly those that come from dominant cultures and privilege. For more privileged people, unlearning is also a commitment to relinquish aspects of one’s self-image, question one’s assumptions, deconstruct one’s prejudices, and show solidarity in ways that may go against one’s material or reputational interests.

So instead of a set of universally applicable "things to learn to create change," what I will present here is more of a theory of how radical collective change might happen, particularly within the context of relatively privileged communities like FC or DAF.

This theory is the following: a prefigurative (online or offline) project will have the potential to bring about radical collective change if two main conditions are in place:

1. this project forms part of a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives, taking a decolonial approach to address the 4 constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality; and

2. a community of belonging and critical discernment is cultivated to nurture this mycelium.

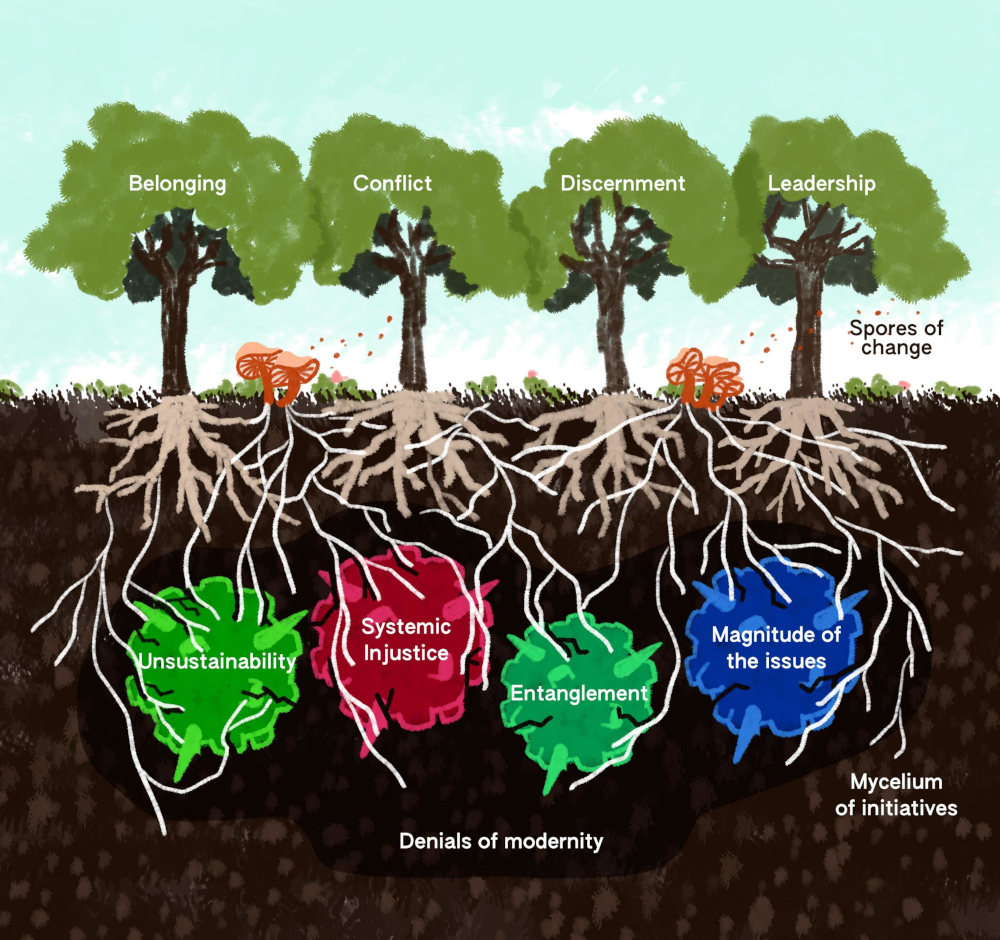

These conditions are summarised in the graph below.

Let's look at each of these conditions!

2. Composting the denials of modernity

The 4 denials

According to the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (GTDF) collective, four denials are fundamental to modernity-coloniality (for more details on what I mean by modernity-coloniality, please see the previous post.) These denials stand for “what we need to (be made to) forget in order to believe what modernity/coloniality wants us to believe in, and to desire what modernity/coloniality wants us to desire” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.51). As such, they “severely restrict our capacity to sense, relate, and imagine otherwise” (ibid.). They include:

- “the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm (the fact that our comforts, securities, and enjoyments are subsidized by expropriation and exploitation elsewhere);

- “the denial of the limits of the planet and of the unsustainability of modernity/coloniality (the fact that the finite earth-metabolism cannot sustain exponential growth, consumption, extraction, exploitation, and expropriation indefinitely);

- “the denial of entanglement (our insistence in seeing ourselves as separate from each other and the land, rather than ‘entangled’ within a wider living metabolism that is bio-intelligent); and

- “the denial of the magnitude and complexity of the problems we need to face together (the tendency to look for simplistic solutions that make us feel and look good and that may address symptoms, but not the root causes, of our collective complex predicament).” (ibid.)

I now consider that the root of the current socio-ecological predicament can be described as a modern-colonial way of being. founded on separation (between humanity and "nature", between people with different hierarchies of worth, etc.) and dualisms that constrain what is possible to do, think, and be (mind/body, reason/emotion, man/woman, etc.). And this way of being is maintained through the 4 denials above. So from that perspective, creating radical collective change is, first and foremost, about facing these denials - and composting them.

On the artwork above, the 4 denials appear as big chunks of toxic waste poisoning our cultural soil, and preventing us from being, sensing and thinking differently. I use the metaphor of a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives to speak of projects and groups who are focused on breaking down these toxic matters and transform them into nutrients - just like saprophytic fungi, which are vital to the living world as decomposers of organic matter and builders of soil: these fungi can digest pesticides, explosives, crude oil, plastics, drugs, and more! (and humans can partner with them, in a process called mycoremediation)

When the fungi thrives, it will reproduce by producing mushrooms. The latter will disseminate spores that will be carried by the wind – or other means of communication – to other social contexts. Here, we can imagine this taking place when interesting projects and initiatives inspire others to take place elsewhere.

My own experience: Injustice and psychedelics

It feels important to say a few words about my own experience of sensing-thinking (sentipensando) about these four denials, as they manifested - and still do - in myself. In the words of V. Machado de Oliveira (2021, p.53), “Modernity is… faster than thought itself, as it structures our unconscious” - so I won't get rid of them anytime soon, as I have limited control over my subconscious ways of being. But with the help of others, I can try to work on these patterns and compost them a little more every day.

I consider that my involvement in the Deep Adaptation Forum – and my intention to undertake this PhD research – came as a result of my growing awareness of the widespread denial of unsustainability, and that of the magnitude of current challenges (see the introduction). And I believe my engagement with these issues has led me to consciously (attempt to) relinquish several beliefs and other mental structures, on the cognitive level – including the theories of sustainability policymaking that I studied as part of my Masters degree, over a decade ago; on the affective level – such as dreams of “fixing the world,” or my avoidance of the topic of death; and on the relational level – including the fuzzy sense that “someone else will clean up all that mess!”

It was only later that I started to more consciously address the two other denials.

As I wrote elsewhere (see Annex 5.2), it was my encounter with Nontokozo Sabic in 2020 that prompted me to re-engage with the visceral sense of injustice that struck me when, on the first day of my Masters programme in sustainability, I learned that the countries that were most affected by climate change were the ones that had contributed the least to this phenomenon. Over the following years, perhaps as a result of my social context, I lost sight of this injustice. When I joined the DAF Core Team, in early 2019, I did not notice that our activities were framed entirely around the collapse of the way of life enjoyed by people like my colleagues and I – middle-class people from the Global North. Until encountering Nontokozo, and sensing the extent of the trauma visited upon her, as a Black and Indigenous South African woman, by the centuries of racism, colonialism, heteropatriarchy and exploitation that accompanied European countries’ violent conquest of the world. Later on, she and I took part in the founding of the D&D Circle, whose aim was to reflect on and address issues of systemic oppression within DAF – that is to say, to help more of us, in a predominantly White, Western and middle-class network, face the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm that enabled the rise of industrial civilisation, and led to global heating and other aspects of the planetary ecological catastrophe.

This was very challenging work (see this other summary), and Nontokozo was a key enabler of unlearning for the rest of us in the circle. Importantly, we did more work composting the "shit" in ourselves than taking action to change social and political structures. Clearly, this is not enough - but perhaps it can be viewed as a starting point? In any case, I do not believe this work has been (primarily) performative, and (only) motivated by the desire for forms of “personal development” that are irrelevant to the global predicament. On the contrary, I consider that this process of “inner composting” is wholly relevant to the challenges of our time, and a necessary premise to any outward-oriented action – i.e. challenging the unjust power structures built atop the harmful ways of being embodied in modern humans. It is a fundamental part of the task of unlearning one’s privilege.

My involvement in D&D was also the occasion for me to venture into even more complex territory, which speaks to the connective characteristics of mycelium: the denial of my own entanglement within the planetary organism – the fourth constitutive denial of modernity. This was triggered by a psychedelic experience involving psychoactive mushrooms. Through discussions in D&D, I discovered the work of the GTDF collective, and in particular, of Cree scholar Cash Ahenakew, which helped me to reflect on this experience. I started to understand that I had been raised into a culture of separation, obsessed with meaning-making and control; and that composting this culture would have to involve letting go of the desire for the totalisation of knowledge (along with certainty, coherence, control, authority, and perceived unrestricted autonomy) - driven by what Ahenakew calls the symbolic-categorical compass - in order to sense more fully into the fundamentally interconnected nature of the universe and of our place within it.

Only by decluttering myself of this addictive habit of being could I begin to reactivate my vital compass, by which I would become more accessible to the bio-intelligence in the living planet-metabolism (which is too vast to be fully understood by human intelligence) - and which would drive me to manifest a form of responsibility and accountability "'before will', towards integrative entanglement with everything: ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’."

I know that this will be a lifelong process of cognitive, affective, and relational unlearning for me. I have decided to integrate psychedelics - along with mycology! - as a regular practice in my life, in the hope of facilitating this composting, and to embody it more; and I try to do so without falling prey to the habit of simply consuming experiences, which our modern-colonial culture prompts us to do. I recommend this rich blog post, by three members of the GTDF collective, for useful insights in this regard.

But enough of me! Let's go back to my case studies of FC and DAF. Did I witness the growth of a mycelium of initiatives, facing the 4 denials of modernity, within either of these communities?

Composting "shit" in FC and DAF

DAF

DAF was started from the premise that the global industrial society is fundamentally unsustainable, and that its collapse is either possible, inevitable, or already ongoing. This is a clear acknowledgement of two of the denials above: that of the unsustainability of current social and political systems, and of the magnitude of our global predicament.

Besides, as I have shown previously, DAF foregrounds the need for enabling and embodying loving responses – and thus, cultivating new forms of relating – as a primary way to confront this predicament. Within the network, several communities of practice are engaged in the development of modalities, such as Deep Relating and Deep Listening, which invite participants to relate differently to one another. Others, such as the Earth Listening or Wider Embraces groups, bring more attention to one’s personal and collective entanglement within larger spheres of being, from the planetary to the cosmic (see Chapter 5). Finally, the activities of the D&D circle and its associated community of practice directly address systemic oppression and injustice. So there are definitely DAF spaces and groups that are facing into the denial of entanglement (by composting the philosophy of separation and othering in modern-colonial culture), and the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm.

Great! Does this mean that radical collective change is happening thanks to DAF? It's a bit more complicated. First, only a small number of DAF participants take part regularly in the activities of groups and spaces like Wider Embraces or the D&D circle - and even fewer people (if at all) seem to take part in practices that confront all four of the constitutive denials of modernity, which means that many blind spots might remain. For example, engaging in practices focused on reconnection and spiritual oneness without confronting the denial of systemic harm and historical injustice can allow for spiritual bypassing of these issues to take place. This points to the need for DAF to encourage a wider acknowledgement of the value of these various modalities and groups – and in particular, to centre the recognition of historical harm and injustice as an integral part of DA discourse, which thus far is only starting to happen (Annex 5.4).

Nonetheless, my sense is that there are potential factors of radical collective change in DAF - but the mycelium is yet to evolve fully.

FairCoop

From my observation of the FC website and documents, and my conversations with participants, it seems that this community mainly acknowledged the limits of the planet, and thus of the need for radically new forms of politics and economics. However, there were few signs of a deep awareness of the magnitude of the global predicament, of the pervasiveness of systemic harm and the heritage of historical violence, or of the ontological entanglement of humanity within the wider planetary metabolism. On the contrary, an important finding from this case study is that there was little reflexivity in FC around participants’ “ways of being,” or to the quality of their relationships.

So in terms of the framework presented above, it doesn’t seem that FC showed potential for radical collective change to take place through its activities.

But like any living beings, fungi need the right environment in order to grow and thrive. Let's now turn to the second main condition that I perceive to be essential for a prefigurative community to have the potential of creating radical collective change...

3. Communities of belonging and critical discernment

In theory, nothing prevents individuals with access to the internet or a reasonably well-furnished public library to start facing the constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality. But in practical terms, given the magnitude and difficulty of the (un)learning that this entails for an average human being socialised into modern society, I doubt the feasibility of going very deep or sustaining such efforts on one’s own – or the possibility of initiating relevant projects – without the company of dedicated (un)learning partners. What then might be some minimal enabling conditions that may allow such radical change to be undertaken on a collective level, as part of prefigurative initiatives?

My experience has led me to sense-think (sentipensar) that a delicate balance of belonging, space for generative conflict, emergent leadership, and critical discernment, is required for a community ecosystem to emerge in which a mycelium of change may grow and prosper. This refers to the trees within the artwork I showed earlier on: they live in symbiosis with the initiatives forming a mycelium that slowly decomposes the denials of modernity, described above.

Let's have a look at each of these trees...

The four trees of community

Cultivating trust and belonging

How to remain in relationship with someone who does not seem to be looking at the same reality - or who just gets on our nerves? The question is all the more complex when these relationships are maintained by electronic means, between people who aren’t present to the same local context… especially when the means of communications, in themselves, amplify political polarisation and keep us trapped in "bespoke realities" - among other ills I described earlier.

My research has led me to believe that online communities can provide a sense of trust and belonging that, in itself, helps to reduce stress and anxiety in an increasingly chaotic and unpredictable world.

I think that in order to potentially bring about radical collective change in the midst of collapse, for instance by enacting decolonial approaches, participants in prefigurative communities need to engage in at least three simultaneous efforts:

- build strong relationships and a solid foundation of mutual trust, which tends to work well within small affinity groups, and cultivate an ethics of care;

- establish safe enough social learning spaces and communities of practice, in which participants may stay at the edge of their knowing, and critically examine and discuss what they see happening in the world at large as well as their personal and collective experiments, without fear of compromising their relationships; and

- develop their negative capability – that is, the capacity “to live with and to tolerate ambiguity and paradox,” “to tolerate anxiety and fear, to stay in the place of uncertainty” and thereby “engage in a non-defensive way with change, without being overwhelmed by the ever-present pressure merely to react” (p.290).

My research has led me to discover certain modalities that have generative potential in this regard. For instance, paying attention to “hot spots” during meetings can help interpersonal tensions and dissatisfaction to be expressed and normalised (Annex 5.3). Deep Relating is a useful process to examine the stories that are we often reproduce unconsciously in how we think, and what we say or do (Chapter 5). As for small affinity groups meeting regularly, such as microsolidarity “crews," they can work as useful containers in which to develop strong relationships, for the productive examination of failed experiments.

Leaning into conflict

It also seems necessary to develop spaces in which to productively examine and work through conflict when it occurs, in order for deeper mutual learning and understanding to emerge – as I have experienced in the D&D circle.

Conflict has been a source of much pain and difficulty for me these past 5 years, but also a source of personal growth and understanding - for me, and for the groups I was part of. In my case, I have been invited to unlearn much of my conflict avoidance, which is a characteristic of white supremacy culture, and to consider how I tend to ignore my feelings of discomfort within a group or a relationship. I agree with Stephanie Steiner (2022, p. 273) who states that “Learning to engage with conflict in generative ways is an important skill for delinking from the colonial matrix of power and relinking to life-affirming pathways.”

While it remains difficult for me to lean into conflict, I have become better able at doing so. I give credit in this regard to the explicit agreements made in certain groups I am or was part of, recognising that conflict is a normal aspect of life, and one that can be a source of deeper trust and understanding when explored with care and respect.

It is important not to confuse interpersonal conflict and institutional violence. But “what we practice at the interpersonal level is important and is part of how we get to larger structural change” (Steiner, 2022, p.276), as other scholar-activists such as adrienne maree brown (2017) have noted. For me, leaning into generative conflict is a primary pillar of radical prefigurative practice.

Embracing (distributed) leadership

In order for a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives to flourish, a community should not be "leaderless" but "leaderfull": the challenge is for the capacity to take action, and generate enthusiasm and support from one's fellow participants, to be distributed - not concentrated in the figure of one particular leading figure. People who have the energy and creative capacity to start something new should be able to do so, without falling into power-over patterns (telling others what to do) - or being perceived as accumulating power injustly, and thus discouraged from doing anything.

Through this research, I got over my aversion to the word "leadership" as I discovered its importance. I have witnessed generative ways of encouraging self-organisation and creative endeavours, so I know it is possible - although again, culturally, people who grew up in modern-colonial cultures (accustomed to being told what to do, and to bossing others around) have much to unlearn. Some methodologies and philosophies of organising, such as Sociocracy or Prosocial, may help in some regard, but fundamentally it's a matter of deep cultural change. Learning citizens, or system conveners (see here), should be encouraged to step up in order to help the whole community to (un)learn new ways of being, knowing, and doing.

A form of leadership that seems particularly crucial, particularly within contexts in which people are attempting to address the denials of modernity-coloniality, is that displayed by "key enablers" - that is, people with more experience with a certain culture or practice, who embody the change that others are pursuing. Their presence seems essential for (un)learning to take place.

Critical discernment

Last but not least, building trust and belonging, leaning into conflict, and fostering distributed leadership, are all elements that can help critical discernment to grow in community participants. This is essential, considering that decolonial forms of change are a matter of deconstructing unconscious ways of being, knowing and doing - we need to be self-reflexive and critical of how we may be reproducing unhelpful patterns.

When building communities of trust and belonging, for instance, we can reflect on how to do so without reproducing "us-against-them" dynamics, and echo chambers. If some people in the community start thinking differently, should they be excluded - or might their views help others discover their own blind spots? How to create conditions and containers enabling people to be authentic and in disagreement without everyone freaking out and splitting apart - or forgetting our mutual interdependence (our entanglement)? How to avoid slipping into mutual "coddling" and conflict-avoidance? These are all rich areas of (un)learning.

As for conflict (like the expression of anger and rage, mentioned in the last summary), when treated as a fertile friction/encounter, can help reveal people’s different exposure to systemic injustice and their entanglement with different layers of the planetary metabolism. For this reason, it may be a source of critical discernment. But when the conditions don’t allow these conversations to happen, and when people are not willing to “sit in the fire,” communities fall apart and no more (un)learning happens (as I believe happened with FairCoop).

As for leadership, it invites personal and collective discernment to develop around issues of power and privilege. For instance, a community may view itself as "egalitarian," and yet the older and best-connected members will find it much easier to have their way and start new projects than new folks, who don't yet know the ropes or where to express their views. And it is easier to take action when coming from a socio-cultural background that has granted one more self-confidence and a sense of legitimacy - how to make it easier for people who have neither of these advantages?

There are probably more trees in this grove that works symbiotically to help compost the 4 denials of modernity - but for now, these are the ones that I have spotted. To what extent were they present in FC and DAF?

The community ecosystems of FC and DAF

From what I wrote earlier, it seems that FC did not create enough space for the cultivation of critical discernment, for instance with regards to the risks of being exposed to speculative financial systems, or to the issues of maintaining two different values for the currency Faircoin in spite of the cryptocurrency market crash. Besides, when severe conflict erupted, there were no capabilities in place for conflict transformation and mutual learning to occur. And while a number of bold projects were initiated within FC, it appears that the notion of leadership remained mostly conflated with the role of the FC founder, and that the community had neither the structures nor the norms and values that would have enabled leadership to be more equally distributed and acknowledged. It is unsurprising to me, therefore, that no mycelium of radical change-oriented initiatives was allowed to grow in FC.

In the case of DAF, the community was founded on the premise that the collapse of industrial society was underway, and that this reality was widely unacknowledged. From the beginning, cultivating critical discernment with regards to various forms of denial, and to the nefarious influence of harmful ideologies reproduced unconsciously, was thus an important theme within DAF, as exemplified in the methodology of Deep Relating. This attention was also repeatedly manifested in the community dialogues organised regularly within the network, to take stock of activities taking place and decide on new strategies.

However, likely as a reflection of the dominant culture from which DAF has sprung, critical and difficult conversations were not always welcome. For instance, discussions on whether a large Facebook group dedicated to talking about collapse was indeed helpful and relevant, considering the triggering nature of the topic and the difficulty of engaging in true dialogue over such a tool, were sometimes shut down. And very little common sense-making and restorative discussion occurred on the topic of Covid-19 policies, in spite of the controversy that has occurred in this regard in the realm of digital information and beyond. Besides, as a participant in the D&D circle, I was disappointed by the relatively low number of participants displaying an interest and willingness to engage critically with the topics of anti-racism or systemic oppression in general. Overall, it may not be unfair to say that a culture of “being nice” and “mutual coddling” remained very present in most DAF groups. While this may have fostered a sense of belonging and emotional safety, it likely prevented more collective discernment to emerge, and thus for the constitutive denials of modernity to be more fully confronted through mycelial, change-related initiatives.

With regards to conflict transformation, social learning occurred over time in certain groups I was part of, most notably the D&D circle. As a result, I feel better equipped to engage with conflictual situations. But it was more difficult for me to assess the extent to which this has occurred elsewhere in the community.

Finally, a culture of collaborating in small teams slowly spread in DAF (see this other summary), and the community stopped relying on a single leader since DAF Founder Jem Bendell stepped down from his responsibilities in September 2020. These were encouraging signs, signalling the uptake of distributed forms of leadership. But it remains to be seen how things will evolve now that the DAF Core Team was disbanded in 2023, leading to a new Sociocratic governance model.

4. So what about actual radical change?

In the sections above, I have described the two main conditions I view as essential for a project to have the potential to create radical collective change:

- this project forms part of a mycelium of change-oriented initiatives, taking a decolonial approach to address the 4 constitutive denials of modernity-coloniality; and

- a community of belonging and critical discernment is cultivated to nurture this mycelium.

I have shown that neither FC nor DAF seemed to have projects forming such a mycelium of initiatives - although put together, DAF groups and spaces addressed all of the 4 denials of modernity, in a somewhat fragmented and partial fashion. As for the second condition, the "four trees" were more present in DAF than in FC. So overall, DAF showed more potential to generate radical collective change than FC - but neither of these communities actually did so, in my definition, at the time of this research.

Now let's imagine the case of a community in which both of these conditions are met. How would someone assess whether this potential change has become, or is becoming, actual radical collective change?

My current working theory is that radical collective change would involve people facing the four denials of modernity, and as a result, experiencing deep re-orientations in their lives (and those of others) - away from the habit of being that characterises modernity-coloniality.

What do I mean by “deep re-orientations”? And how might one assess them?

Since I consider radical collective change to involve, first of all, a full acknowledgement of the four denials of modernity, I would consider a “deep re-orientation” as involving changes in people’s lives that are enacted as a result of this consciousness, and which are viewed as transformative by the person. And in order to be collective, these changes should involve more than an individual – they would probably have a collaborative nature.

However, because modernity is faster than thought itself, it is inevitable that our desires include the need to “look good,” “feel good,” and “move forward” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p.113). How then to assess whether these changes are merely performative, tokenistic, and transactional, or rather do constitute radical collective change?

I suspect that this requires an ongoing critical self- and mutual assessment, that should at least include investigating:

- how a person is (re)orienting their life as a result of their decision to face the denials of modernity-coloniality;

- what the observed results of this (re)orientation are – on the person and on others;

- what stories are at play for the person as they enact these (re)orientations (how they interpret what they are doing); and

- how critical they are of these stories, and sceptical of their own subconscious investments and desires.

In other words, whatever one does with the explicit intent to address one or several of the denials of modernity-coloniality, could be performative, or constitute radical collective change, depending on how and why they do it. This would depend on the intellectual and relational rigour brought to this initiative - and therefore, on the material, affective and relational impacts it creates.

I suppose that the stronger one’s commitment to self-criticality, the more likely these (re)orientations may constitute radical collective change. From a research perspective, the Wenger-Trayner social learning methodology I used in Chapter 5 has been helpful to evaluate the first three aspects listed above, but has not allowed a strong focus on the fourth to take place. Cooperative inquiry group processes aiming at supporting the capacity for critical humility may be particularly useful in order to challenge “self-delusion, avoidance or denial,” in a spirit of mutual care and compassion.

This is all guesswork for now, as I haven't been able to evaluate actual forms of radical collective change during this PhD project. Stuff for future research!

So, that's it folks... I think this will be my final summary I will write for now. In case you'd like a recap of the main findings from this research, a summary of "issues for future research and practise," and a beautiful quote from Chief Ninawa Huni Kui, please check out my Conclusion chapter - it's much shorter than the other chapters in my thesis, I promise! And hopefully, more readable too.