- Introduction: Setting the scene

- Tools of emancipation, or tools of alienation?

- My research approach

- Learning from our failures: Lessons from FairCoop

- Introducing the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF)

- The Diversity & Decolonising Circle

- The Research Team

- The DAF Landscape: Cultivating relationality

- Considering DAF from a decolonial perspective

- Radical collective change

The DAF Landscape: Relationality in practice

(a summary)

As I mentioned previously, during this project, three distinct research streams unfolded simultaneously in the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF):

- The Diversity and Decolonising Circle (D&D)

- The Research Team

- DAF as a landscape of practice

Each of these research streams was an evaluation of the social learning processes that Wendy and I documented within DAF, using the Wenger-Trayner methodology. To read more about communities of practice and social learning spaces, see this post.

TL;DR:

- Many DAF participants have found the network helpful to integrate the difficult emotions that they experience due to the global predicament, and transform these emotions into generative action.

- Another important area of personal and collective change that has been explored and highlighted in DAF has been the cultivation of new forms of relationality, to overcome the mindset of separation and "othering" that characterises the mainstream modern culture. This has been more of a focus within DAF than forms of activism calling for changes in socio-political structures.

- These new ways of being and relating have been fostered especially in small, self-organised groups, through the use of modalities such as Deep Relating, Earth Listening, or Wider Embraces.

- It is possible that in this way, DAF has been enabling many participants, collectively, to move away from instrumental consciousness, and into collaborative social or ecological consciousness, through a process of worldview transformation. This process involves developing more criticality towards one's own culture and society; self-reflexivity; a greater ability to be aware of and attentive to the consciousness of others; and the capacity to build emotional connection and the capacity for empathy. However, further research is needed to confirm this aspect.

- Several factors have been mentioned as playing an important enabling role to allow this social learning to take place. This includes elements of design of DAF social learning spaces (a clear purpose and focus, the presence of moderators or facilitators, regular video calls...); a focus on relational and somatic processes in small groups; attention to group culture and atmosphere (psychological and emotional safety, making everything welcome, focusing on relationships...); and the social make-up of these groups (like-minded people, diversity, and the presence of key enablers).

- On the contrary, disabling factors included technical problems with communication platforms; and organisational issues, concerning network vision and purpose, power and leadership, and how to handle the anti-racism and decolonising within DAF.

- Self-organisation has been an important guiding principle and organising method within DAF. It has been encouraged through the creation of social structures providing scaffolding (such as allowing small groups to form autonomously); and through self-organising events, allowing people to meet and form groups. Some of these efforts have been more successful than others, and much (un)learning still needs to happen in order for these methods to be widely applied and understood in the network.

- DAF's emergent governance model and strategic orientation have been experienced as confusing by some participants, who regret the lack of a specific call to action. It may also have made it more difficult for the network to find the funding to keep going.

1. Landscapes of practice

I will now summarise some key findings from the third research stream - on DAF as a landscape of practice. But what is that, exactly?

Previously, I introduced an important concept in this research project - that of communities of practice, as "groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn to do it better as they interact regularly." In their social learning theory, Etienne and Bev Wenger-Trayner (2015) argue that such communities tend tend to form part of complex and political landscapes of practice, involving other communities, which are brought together by a common body of knowledge. Learning can be seen as taking place not only within each community of practice, but also in relation to this broader landscape. In this way, much learning may happen at the boundaries between communities. In my view, DAF can be viewed as a complex landscape, bringing together various communities of practice. Several such communities existed in DAF over the period of our research - such as the Facilitators' Group, or the D&D Circle.

What are the main seeds of change that were cultivated within DAF social learning spaces and communities of practice, across the landscape? What were the conditions – or the “soil” - enabling these changes to happen, or preventing them from happening? Who were the “sowers” helping to nurture the soil and to sow the seeds - and

what kind of learning leadership did they enact in doing so?

There are many ways of answering these questions, depending on how one orients the seeds-soil-sowers "prism." For a (very) detailed presentation of these findings, please see Chapter 5 of my thesis.

In this post, I will start by discussing the affective and relational aspects that participants have mentioned as constituting major areas of learning and change in DAF. Then, I will turn to the enabling factors, including self-organisation, that have made these changes possible. In the next summary, I will use a different perspective, and discuss DAF's relevance to radical collective change to future sowers, from a decolonial perspective.

1. Seeds of personal and collective changes

1.1 Does thinking about collapse drive people to hopelessness and inaction?

Let's start with an opinion commonly voiced by critics of DA, and collapse-focused networks and movements: that believing in societal collapse leads people to hopelessness, and therefore, to abandon all drive to create social change. For example, scientist Michael E. Mann views DA as a “doomist” and “disabling” framing, dissuading people from taking part in political processes to demand systemic changes in the face of climate change, and thus reinforcing ongoing trends towards “inaction” and “disengagement.”

Several leaders of XR have acknowledged the complementarity between their approach and the DA framework, and even the impetus that DA brought to their action. And this action has been quite impactful, at least on public discourse in the UK. So that already constitutes a serious challenge to any arguments that DA is counterproductive for generating political pressure on topics like climate change...

Now, it's confirmed: the data from this research project show that these arguments can be fully dismissed.

Indeed, results from the three surveys disseminated in DAF, and from several interviews, show that respondents became better able to live with the difficult emotions they experienced with regards to the global predicament, and were feeling less isolated, less despairing, and less fearful as a result of their participation in DAF groups. Besides, a clear majority of the CAS survey respondents had decided to change their lives as a result of their engagement with the topic of collapse (including on practical, social, psycho-spiritual, and moral dimensions), and the respondents most deeply involved in DAF were much more likely to have taken action. These results confirm those obtained in a different survey, which indicated that people are more likely to lead in their community if they anticipate societal collapse. These results are also consistent with the results obtained in another qualitative research project on DA carried out in Germany by Chris Tröndle, which found that none of the respondents were driven by apathy by their anticipation or experience of collapse. Indeed, they tended to be involved in various forms of activism or social change-oriented endeavours, and to draw a sense of inspiration and empowerment from their participation in a community of like-minded people.

Several of the research conversations I carried out confirmed the importance of experiencing belonging and community as a way to generatively engage with difficult topics such as that of societal collapse.

However, my research data also indicates that many participants do not view taking part in DAF as a form of activism. For example, most CAS survey respondents were not interested in discussing societal collapse from the perspective of political change, although more seasoned participants did express a sense of strong curiosity in this topic. But this does not mean that DAF participants do not engage in activism elsewhere: over 12% of respondents to the DUS survey said they were involved in various activist groups and movements. This seems to show that most participants do not consider DAF as a political-change-oriented network, and yet are yearning for such change. Correspondingly, a clear majority of respondents to the RCS survey aspired to various forms of radical collective change, but only a minority among them viewed DAF as facilitating the “radical reshaping of political and economic structures” to which they aspired.

Therefore, what emerges from my research is that while engaging with the topic of societal collapse may be a source of difficult emotions, this in itself does not seem to be a cause for apathy – particularly when one can benefit from feeling part of a community of like-minded others. Smaller affinity groups appear particularly well suited to mutual support and encouragement, as the example of the D&D circle clearly shows. In fact, most of my survey respondents and interviewees appear involved in various prosocial activities and endeavours, which can include political activism. However, few of them consider DAF the conduit for this activism taking place.

Whether DAF groups will grow more closely involved in efforts aiming at generating political change remains an open question. But during this research, dominant aspirations in the network - particularly among more deeply involved “sowers” - concerned other dimensions of collective change: “Orienting towards connection, loving kindness and compassion for all beings” and “A transformative shift in worldviews and value systems” (as discussed in this report).

Let's take a closer look at these intentions, as another important kind of "social learning seeds" cultivated within the landscape of DAF.

1.2 Relationality as an answer to planetary crises

1.2.1 The need for inner transformations

More and more scholars, writers and artists are calling for deep inner transformations, in how we view ourselves and the world and how we approach knowledge and the act of knowing. They say we must embrace a relational approach, which pays attention to how all of life (and the universe) is composed of relationships, and argue that “the current multiple crises are due to an alienation from ourselves, others, and the natural world.” Here's French writer and public intellectual Alain Damasio, for example:

"The current political crisis, in Western countries, is one of our relationships to each other. There is a growing anaesthesia to the modes of attention and availability that we nurture with others, including all living beings…. Therefore, the first step of establishing what could be termed a ‘polytics of life’ is to reactivate our capacities to relate – in all forms and with all our strength. Indeed, contrary to what the liberal doxa pretends, one is not freed through individual independence, but through interdependences and relationships: through what these allow and weave between us in terms of fertile possibilities."

But how to envision this kind of inner transformations having any concrete effect in the world?

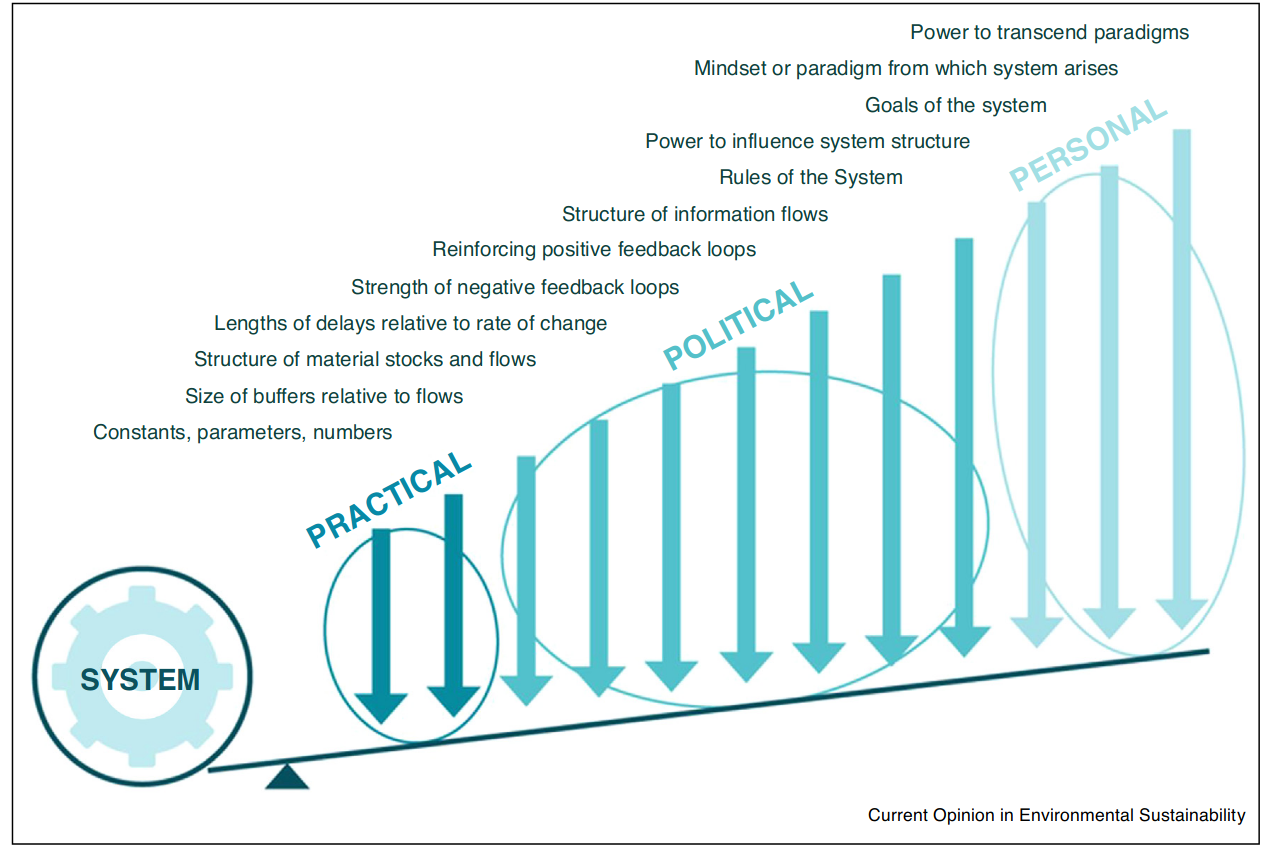

The work of systems theorist Donella Meadows shows that transforming people's inner worlds is the deepest, and least explored, "leverage point" that can help shift social systems to a completely new state - as shown in the graph below.

Leverage points for systems change based on Meadows (1999) and their relationship to the practical, political and personal spheres of transformation. Source: O'Brien (2018)

So to create deep change in people's lives and in society, it seems crucial that our modern culture start recognising that "we are made entirely of relationships, as is the whole of the natural world" (Spretnak, 2011). This consciousness should infuse and inform all political and practical action, because the challenges we face are adaptive, not just technical - addressing them actually requires new beliefs, values, and worldviews.

Increasingly, activist circles and social movements are also focusing on relationships and fostering a relational ethics as a primary step towards creating social and cultural change. For example, activist and scholar adrienne maree brown (2017), drawing on the seminal work of leadership theorist Margaret Wheatley, places the long-term transformation of relationships at the heart of her theory and practice of emergent strategy:

"Focus on critical connections more than critical mass—build the resilience by building the relationships."

Similarly, the participants in the arts, research and social movements collective Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures argue that “it is the quality of our relationships (to all beings) that determines the political possibilities that are viable in any particular context.” For them, it is imperative to create new kinds of social configurations based on a politics that may "uphold the integrity of our relationships and the responsibilities that follow from them.”

To what extent can DAF groups be viewed as fostering the emergence of more relational worldviews and ways of being in the world?

1.2.2 Relationality in DAF

An important part of the framing of DAF since its creation has been an emphasis on fostering new forms of relationality in response to the global predicament (see Annex 5.4 for details). Turning to love, and overcoming the mindset of separation based on the “othering” of other people and the natural world, was described in the blog post "The Love in Deep Adaptation: A philosophy for the forum" as a fundamental aspect of “collapse-transcendence” – i.e. “the psychological, spiritual and cultural shifts that may enable more people to experience greater equanimity toward future disruptions and the likelihood that our situation is beyond our control.”

Although the Forum started off with a stronger focus on “collapse-readiness,” referring to “the mental and material measures that will help reduce disruption to human life – enabling an equitable supply of the basics like food, water, energy, payment systems and health” - this approach did become a central element of both the philosophy and the practice of the Forum. It was embodied for instance within the community of practice of DA Facilitators, who have been offering a number of free online gatherings on a regular basis, several times a week, particularly since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

So it is perhaps unsurprising that when the research team asked DAF participants about important forms of social learning they were experiencing in the Forum, many replies suggested that experimenting with new ways of being and relating was a very important part of their involvement. Many said they were finding new ways of relating to self, others, and other-than-humans or the planet at large, and reported experiencing greater well-being thanks to their experience of these relational modalities.

But this goes beyond the personal level - relationality has cultural and political implications, because DAF is a prefigurative community. Prefigurative groups seek to embody in their practice itself those forms of social relations, decision-making, culture and human experience that are ultimately desired for the whole society. My sense is that a relational focus is at the core of the prefigurative practice of DAF groups, and that the cultivation of relationality appears to be an essential “seed of change” growing within the network.

The D&D circle [link] is an example of a DAF group in which strong bonds of trust and belonging were consciously cultivated through regular calls and storytelling, and through the willingness to engage in conflict transformation processes. Most of the experiences of personal transformation mentioned by circle members have to do with various forms of relationality, including:

• understanding one’s own implication in global systems of oppression (relation to society or the world);

• finding unprecedented psychological safety in the presence of others (relation to the group);

• overcoming one’s internalised oppression and feeling empowered as a result (relation to oneself).

Prioritising mutual care and relationship-building was an important aspect of making these changes happen in the circle, and developing the stamina to engage in the various endeavours championed by this group, which were emotionally challenging. More recently, the collaborative efforts initiated in support to women in Ukraine among several DAF participants were clearly catalysed by the strong mutual trust that had been cultivated between them.

While the above may appear to be only small instances of collective change enabled through relationality, they remind me of the widespread, self-organised mutual aid actions that took place in various places around the world, following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic - from Athens to London and beyond - embodying responses motivated by a clear relational ethos.

Could it be that communities (online and offline) that are placing relationships front and centre, all around the world, are helping to sow the seeds of a more caring culture, one that will let go of individualism and the myth of separation, and enable humans as well as other-than-humans to survive the various forms of social and ecological collapse that the dominant culture is precipitating? And what if these communities were even capable of facilitating collective shifts in consciousness?

1.2.3 Fostering social and ecological consciousness?

Scholars have shown that modernity has led to the dominance of instrumental consciousness, which mainly values what humans can accomplish by objectifying the self, others, and the rest of the living world, as tools or resources. This instrumentalising tendency leads to a “deeply truncated” vision of the self, which rejects or disregards “the quality of our relationships to each other and to our context, our inherent capacities to heal, renew, and evolve, and our worthiness simply to sojourn as an integral inhabitant of the earth” (p.11). This view has caused suffering, alienation, a disregard for the cultivation of the spiritual life, and is at the root of the current social and ecological predicament.

These authors call for transformative practices and collectives that can help nurture a very different way of being in the world: ecological consciousness, which is rooted in the intimate knowledge and felt sense that the personal self is formed by co-constituted relationships, including those we have with other human beings, but also other species, and "all the powers of the world.” Maybe DAF groups constitute helpful spaces for this consciousness to develop?

If so, developing such consciousness may constitute what other scholars call a world-view transformation – i.e. “a fundamental shift in perspective that results in long-lasting changes in people’s sense of self, perception of relationship to the world around them, and way of being.” This means more than just new ways of seeing the world intellectually, but something much deeper: changes in our epistemology - or how we know what we know - and in our ontology - the basic categories through which we make sense of reality. Once those are transformed, our behaviour cannot stay the same.

Under the right conditions, transformative experiences can lead to expanded social consciousness – that is, higher levels of conscious awareness that one is part of a larger whole, and of an interrelated community of others. This is correlated with more compassionate and service-oriented behaviours, as people are “inspired to act as agents for positive change in their immediate communities and beyond.” For Schlitz, Vieten and Miller, several capacities are necessary to develop in this process, such as:

- criticality with regards to how our lived experience and subjectivity are shaped by ideology and hegemonic power relations, as well as other social, cultural, and economic factors;

- self-reflexivity, as a key to increased cognitive flexibility;

- a greater ability to be aware of and attentive to the consciousness of others...

- and thus, the capacity to build emotional connection and the capacity for empathy, which may lead to the desire to improve the well-being of others. While this desire may initially manifest as a unilateral mission to save others, expanded social consciousness may eventually bring people to realise the limitations of this approach, and to embrace ways of engaging with the world that are collaborative rather than prescriptive.

The authors consider that empowering conversations and storytelling are essential in this regard. Such conversations can be facilitated by modalities that enhance collaborative social consciousness, by surfacing group collective intelligence and wisdom - for example, using Open Space Technology, or Bohmian Dialogue Groups.

Interestingly, several of the modalities that are practiced in DAF groups seem favourable to developing this kind of expanded social consciousness. According to Katie Carr and Jem Bendell, DA group facilitation centres the development of critical consciousness, in that it helps people discern when one’s thoughts or behaviours perpetuate systems of oppression and destruction (criticality); it encourages the acceptance of radical uncertainty, and even viewing the self itself as a fluid and uncertain phenomenon (self-reflexivity and cognitive flexibility); and makes space for the vulnerable expression of feelings, particularly around one’s sense of loss and grief, as a way of relating that encourages deeper compassion and understanding of others and their inner world (emotional connection). These principles are particularly foregrounded in the practice of Deep Relating, which itself is a modality influenced by Bohmian dialogue, designed for the authentic expression of private experience in a group context. Deep Relating invites participants to “a critically conscious engagement with the stories we participate in” and to surface “unconscious patterns within dominant discourse” (p.14). So Deep Relating could help enhance collaborative social consciousness.

Besides, practices such as Wider Embraces or Earth Listening, which aim at exploring directly one’s connectedness with other-than-human, planetary or even cosmic dimensions of existence, may also be helpful in this regard. According to Schlitz and colleagues, “shifts in consciousness need not wait for random life-changing experiences, but can be invited through intentional practice” (ibid, p.31). Testimonies collected through surveys from participants in Earth Listening (EL) and Deep Relating (DR) groups speak to important experiences of unlearning, which seem to correspond to expressions of expanding social consciousness.

Therefore, several elements indicate that the focus on intentionally cultivating new forms of relationality within DAF, be it through the general ethos of the network or through specific practices used in various DAF groups, may be enabling participants to develop or expand their social and ecological consciousness.

Two caveats should be raised, nonetheless. First, most of the participants we interviewed were actively involved in DAF (and could be classified as “Active” or “Occasional participants” following the typology presented in Chapter 5). They tended to value relational process much more than the more peripheral stakeholders (“Very occasional participants”) who answered our surveys, and who tended to be more interested in practical forms of adaptation to the threat or experience of societal disruptions (Annex 5.4). Therefore, it would be important to consider the extent to which the relational framing promoted by more active participants is influential in areas of DAF less involved in online events, such as the DA Facebook group, or the affiliated groups.

Secondly, most of our interviewees stated that their involvement in DAF (or even their “collapse awareness”) was the result of a gradual personal journey, taking place over several years and integrating various influences, towards realising the depth of the global predicament. In other words, they experienced learning about DA as a confirmation of what they felt they already knew, instead of as a sudden revelation. This has been noted in another study involving “deep adapters.” It is thus possible that the same is true for them about the importance of relationality, and that they only found in DAF a place in which to embody a counter-cultural world-view they had already adopted. For those in this case, the network might have been less of a transformative space, and more of a support structure for a transformation having already taken place. Further research would be needed to clarify this matter.

In any case, it is encouraging to notice that of the six factors that Vieten, Amorok and Schlitz identify as critical to facilitate long-term behavioural shifts, following a transformative experience, several seem present within DAF – for instance, the presence of a like-minded social network or community, and a shared language and context.

Let's now look at the different factors that have enabled these social learning experiments.

2. The enabling soil

2.1 What helps the social learning to grow?

What conditions enabled the relational seeds above to grow and thrive? What elements of social and/or technical “soil” have been most favourable to them in DAF – or, on the contrary, prevented them from flourishing?

2.1.1 Various enabling factors

Data from surveys and research conversations helped to surface several categories of factors which DAF participants found helpful to their learning in the network. These categories overlap with one another to some extent:

Social learning space design

Participants valued DAF social learning spaces that had a clear purpose and focus, as well as principles of engagement known to all. DA Facebook group members, for example, frequently mentioned their appreciation for the clear focus of the group expressed in its guidelines document (e.g. it is not about discussing climate news). The presence of moderators – like in the Facebook group – or facilitators – in smaller groups – helping to keep conversations “on track” was also often positively remarked upon. Clarity of scope and facilitation were also considered helpful in terms of keeping discussions stimulating and informative, and thus for them to function as vibrant learning spaces.

Within smaller DAF groups, regular video calls (on a weekly, biweekly or monthly basis) tend to be the norm. Several participants valued the feeling of continuity created by such a meeting rhythm, which enables attendees to build strong relationships over time, in space of geographical distance.

Relational and somatic processes

It is customary, in most DAF online calls, to begin the meeting with a moment of collective “grounding” or “presencing” meditation (see Annex 5.3). This is followed by “check-ins,” during which every participant shares a few words about their current physical and affective state, and any other comments about what may be going on in their lives. Calls usually end with “check-outs” in which people express how there are leaving the meeting.

“First, we have to connect as humans, otherwise the rest of it is useless.”

Participants who regularly take part in DAF calls, for example as part of their involvement with a particular group, have tended to mention such relational and somatic modalities as particularly useful to their learning. Within groups centred on Earth Listening or Deep Relating, most of the meeting time is in fact dedicated to engaging with such processes.

“Such gatherings and experiences have had a deep impact on me. My participation in them has changed how I relate with reality, and it is also changing the way in which I express myself about our predicament - more and more, I stress the need to approach these questions from the point of view of feelings and relating.”

Group culture and atmosphere

DAF participants often mention the importance of psychological and emotional safety within discussion spaces. This sense of trust in other participants is fostered through group agreements, and various textual reference points laying out the ethos in which discussions should be taking place – such as the DAF Charter, or the Deep Adaptation Gatherings Principles, which invite participants to “return to compassion, curiosity and respect.” Safety is also encouraged by a group culture within DAF which aims at making “everything welcome,” including difficult emotions, and at being forgiving of one’s and others’ mistakes. Moderators, facilitators, and other respected members of the community, play an essential role in modelling such behaviours.

“A culture of being able to name what you're observing is really powerful in any group I think, permission for a member to say, 'I'm noticing...' or 'I feel...' and be able to actually speak it into the space, is really powerful.”

Another enabling element is that of encouraging participants to dedicate special care, time, and effort, to sustaining and nurturing interpersonal relationships within the network. On occasion, this may mean setting time aside to work through tensions and conflict, be it happening between oneself and another person, or between other members in one’s group. See Annex 5.3, Section 2.2.4 for an example of a conflict resolution process within the D&D circle.

“The conflict-resolution process that I went through, for some conflict that I was involved in... enabled me to see myself from an outsider’s perspective, and gave me deep insights into how different people with good intentions can approach the same situation.” (Story #4)

Enjoying the company of one’s fellow participants

DAF participants often express their sense of deep gratitude for having found like-minded others, with whom they can share a sense of belonging and community. For many, this is because no one else around them has an interest in the topic of collapse; for some, the sense of belonging may be linked with an even more specific group focus – be it connecting with the Earth in EL, or engaging with issues of systemic injustice in D&D. Enabling factors mentioned above are likely essential in fostering such feelings of community and belonging.

“I feel part of a community of people who are loving and with whom I'm on the same page. This feels extremely rewarding.”

However, this sentiment does not have to mean feeling part of a monolithic, homogenous collective which erases personal differences. In EL as in the DA Facebook group, participants remarked on the insights they gained from encountering a diversity of opinions and perspectives.

Finally, being in the company of others who are trying to be caring and helpful toward one another is also often mentioned as an important enabling factor. Among these important fellow participants, the presence of “key enablers,” in other words “elders” or “mentors” who have been in the network for longer than oneself, or who may have struggled with difficult questions that one is also facing, can also be a source of courage, insights, and inspiration.

Disabling factors

What conditions may hamper social learning from taking place within DAF groups?

Platform issues

A first set of problems has to do with technical characteristics of DAF platforms: some research participants mentioned having issues with Facebook (due to the platform's socio-political influence in society, and its manipulative algorithms); others disliked the clunkiness of Ning. These technical and philosophical concerns were integrated into a reconfiguration of DAF's infrastructure in 2022.

Organisational issues

Former DAF participants explained they had left the network for various reasons. First, some felt at odds with DAF's vision and purpose, lacking a clearer "call to action" (a topic we will come back to, below) on how to reduce harm in practical terms, due to the network's relational focus.

Others had issues with power and leadership in DAF. This included interpersonal issues involving the DAF founder or members of the Core Team - some participants found the network too hierarchical and directive, while others regretted the absence of clearer strategic steering. This shows that self-organisation and emergent leadership were not always embodied helpfully by the people in positions of leadership within DAF, who at times failed to deal generatively with issues of power, boundary-setting, and accountability.

The anti-racism and decolonising agenda

Finally, another recurrent point of tension has concerned discussions of matters of social justice, and in particular, the approach of the D&D circle – whose work has been supported by the Core Team since the beginning (Annex 5.3), and which several members of the Core Team have been part of. Some participants found this orientation stifling and lacking nuance, while others considered not enough was being done to promote social justice awareness and practice in DAF - a recurring criticism being that DAF spaces were often “too cuddly” for people to challenge one another on such issues and develop more “authenticity.”

It is possible that these issues might have proved less contentious, had these topics been more explicitly associated with the “Deep Adaptation agenda,” and mentioned as part of the early framing of the Deep Adaptation Forum. I will return to this point in the next summary.

2.2 Self-organising to make a difference

Since DAF's creation, the Core Team encouraged self-organisation in the network - increasingly so as time went by. The aim was to respond to concerns about the risks of climate-induced societal breakdown, and channel people's energies into networks of peer support - instead of establishing a particular course of action as the main or only relevant one.

How was self-organisation enabled in DAF, and to what extent were these practices successful?

2.2.1 Creating scaffolding

First, structures were created in DAF to encourage the creation and acknowledgement of self-managed teams and groups. The names used to refer to these groups evolved with time - from "task groups" to "circles" and "crews" - but their general purpose and function remained the same: several network participants could band together, and express to the network their wish to collaborate on a certain project or exploring certain themes, more or less formally (at the outset, task groups needed to sign an MoU with the Core Team). These groups could do what they wanted as long as they adhered to the philosophy of DAF. Some of these groups were also supported through monthly capacity-building meetings, in which participants could get to learn the ropes of self-organising and share useful practices among themselves.

Secondly, self-organising events were organised, providing occasions for participants to articulate their aspirations and find collaborators with whom to start these small groups. Between early 2020 and July 2022, 11 online events following an “online open space technology” format were organised in DAF by volunteers - especially from the Collaborative Action Team - with support from the Core Team. Some of these events (such as the 2020 Strategy Options Dialogue) were primarily moments in which DAF participants could express their wishes as regards the future of the network (see Annex 5.4), but also helped new task groups and circles to form (such as the D&D Circle). Others were purely dedicated to forming new teams. These events attracted registrations from over 300 different participants, many of whom were not active within DAF.

2.2.2 Is DAF a self-organising network?

In spite of the efforts mentioned above, it appeared that few self-organised groups succeeded in maintaining their efforts in time. Besides, efforts aiming at supporting the creation of more circles and crews have led to little engagement so far. It is therefore tempting to conclude that DAF has failed to become a self-organising network or community – i.e. one in which “complex interdependent work can be accomplished effectively at scale in the absence of managerial authority” (Lee and Edmondson, 2017).

Nonetheless, research on self-organisation in open sociotechnical networks like DAF shows that such ways of organising tend to take time to emerge, not least due to most people’s lack of experience in this domain. In this regard, it is worthwhile to consider encouraging signs that the practice of self-organisation may be slowly spreading through DAF.

“[Thanks to] many conversations [I’ve had in DAF]... I’ve learned that our way of doing things [in the Collaborative Action Team] is spreading within DAF. I notice, for example, how the Business and Finance group leaders now announce their events as ‘Zoom sessions in an open space context.’ I’ve also heard of teaming processes being used more deliberately, for instance in the DA Facilitators’ group. Now, DAF feels more self-organised, more adaptive and focused on small collectives.” (Story #11)

The testimony above was provided by one of the DAF volunteers who, together with other members of the Collaborative Action Team, has been most instrumental in spreading self-organising practices – such as “teaming,” i.e. working in small teams – within DAF. He points out how the practice of allowing emergent groups to form using the open space format has also been applied within meetings of various interest groups in DAF. Several other volunteers mentioned having become better at teamwork since joining DAF, and credited their fellow participants for their support in getting their group started.

There are also emerging examples of other generative projects emerging in a self-organised fashion within DAF. Between September 2020 and September 2022, a comprehensive evaluation and evolution of the software infrastructure supporting DAF groups was carried out by a group of over two dozen volunteers and Core Team members, who coordinated their research, testing, and implementation efforts in a self-organised way. The expertise of three participants in the domain of Sociocratic project management, who occasionally stepped in to facilitate these efforts, was critical. Thanks to this project, three new platforms were introduced into the DAF, and an existing one was retired. And in November 2022, a DAF volunteer invited several others to take part in the efforts of a self-organised collective offering support to women in Ukraine who suffered sexual assault. Her story shows how the trusting and affectionate connections she had fostered within DAF were critical to this collaboration taking place, as well as her fellow volunteers’ comfort with self-organising.

Overall, it therefore appears that self-organisation – and the skills that support it – was a "seed of change" that was consciously, and influentially, cultivated within DAF. While DAF remained in the early stages of relying on such practices, their diffusion was taking place and may lead to fuller emergence of circles and crews in the future.

But to what extent was this approach to self-organising also part of the "enabling soil" supporting processes of learning and change within the network? And did it also play a disabling role somehow?

2.2.3 Self-organising and (un)learning governance

According to E. Wenger (2009), a social system can be more or less capable of stimulating social learning. And one of the factors that affects this social learning capability is how learning itself is governed in the system. There can be two main governance processes at play:

- learning can be stewarded - in other words, actors in the system can make "a concerted effort to move a social system in a given direction” and "seek agreement and alignment... in order to achieve certain goals”; in contrast,

- learning can also be let to emerge, through the decisions and interactions of participants throughout the system, in various learning spaces, and disseminated by people without relying on more centralised or coordinated processes.

For Wenger, both types of governance are useful for social learning, and should be helped to exist together. While the former fosters the recognition of interdependence and the capacity for joint action, the latter ensures the possibility of unforeseen, innovative ideas emerging from local interactions. Therefore, “it is the combination of the two [processes] that can maximise the learning capability of social systems.”

Besides governance, Wenger also emphasises the role of accountability structures within social systems. A leaderless social learning space might be characterised by horizontal accountability, as participants are, by definition, accountable to one another through their engagement in joint activities; whereas vertical accountability would be much more present, for example, in an organisation relying on a hierarchical decision-making structure – since people “lower down” must report to others “higher up.” Just like the two forms of governance presented above, both forms of accountability can be artfully articulated within a social system to maximise social learning capability, through both emergent and stewarding governance: horizontal accountability, based on negotiation and mutual expressibility, is vital to social learning spaces for peer engagement to be genuine; as for vertical accountability, based on compliance (for example, in the form of commonly agreed rules and agreements), it can help facilitate governance processes across a complex social system.

Wenger suggests that this should take the form of “interwoven learning experiments.” This refers to experiments taking place in semi-autonomous learning spaces without any forced homogeneity, yet with supporting structures in place that can help the results of these experiments to spread beyond their local setting. In this regard, Wenger therefore proposes that social systems may benefit from a centralised role or body which would provide stewarding governance with the specific aim of fostering learning capability.

To what extent does this theory of learning governance help explain the learning capability of DAF as a complex landscape of practice?

As I mentioned above, from the creation of DAF, an emphasis was put on the network aiming to enable the emergence of peer support structures within a DA ethos, instead of directing collective efforts to achieve certain goals. This intention was premised on the impossibility of knowing what might constitute the “right answers” to the global predicament, as the latter was recognised as occurring due to an epistemological crisis – in other words, current dominant worldviews are unhelpful for anyone to know the “way forward”:

The anticipation of societal collapse is therefore to acknowledge a crisis of epistemology and a collapse of the hitherto dominant ways of seeking to know the world…. DA is primarily a container for dialogue that begins with an invitation to unlearn, to let go of our maps and models of the world and to not prematurely grasp at any new ones. That can be difficult because a habit of needing fact, certainty and right answers means people are often uncomfortable being with uncertainty or ‘not knowingness’. (Carr and Bendell, 2021)

This helps to explain the strong focus on promoting self-organisation within the network, in the form of self-convened groups and projects, rather than DAF aiming to achieve certain specific goals, or to materialise a specific vision. It also explains the attention brought to developing alternative ways of relating in groups, particularly within the DA Facilitators community of practice, in order to enable more participants to grow more comfortable with uncertainty and “maplessness.”

In discussing DAF governance, it is necessary to touch on the role of the DAF Core Team (CT), which I have been part of from the creation of the network and up to the time of writing. In official documents, this role was defined as being largely about supporting “the aims, ethos, and policies of DAF” as well as “other emerging areas of work and priorities” – rather than setting strategic goals. During the first year of the network’s activities, the CT relied strongly on stewarding governance to pursue certain strategic objectives, decided with little consultation of other participants, although feedback was invited on the documents laying out these objectives. But gradually, the CT only offered recommendations for focal action areas, on the basis of the outcomes of wide-ranging community consultation processes taking place on an annual basis (such as the Strategy Options Dialogue in 2020).

The CT therefore shifted its role from a focus on stewarding governance to emergent governance. It also favoured horizontal accountability across the network, by encouraging the creation of self-organised teams and groups. But the CT did not relinquish all processes of vertical accountability: for example, it supported a participatory process leading to the co-creation, in March 2021, of the first version of the DAF Charter, which itself is an instance of vertical accountability, among other network policies – such as the Safety and Wellbeing Policy.

Overall, has the CT succeeded in fostering learning capability in DAF, by acting as a centralised body providing stewarding governance while allowing the emergence of “interwoven learning experiments”?

On a formal level, the CT has undeniably supported some of the transversal processes (cutting across dimensions of governance and accountability) which Wenger argues are critical to maximise learning capability – most notably, the creation of autonomous social learning spaces and communities of practice, such as the D&D circle and other groups. Another example might be the public acknowledgement of the learning citizenship exercised by DAF volunteers through the activities of the Gratitude Month in August 2022, and the publication of a “Credits” page on the DAF website, listing the names of contributors wishing to do so. The CT also supported two editions of the Conscious Learning Festival, organised by the research team I initiated in DAF.

In practice, however, it is worth noting that at the time of writing, few self-organised groups have succeeded in meeting regularly over time. To a certain extent, this may be due to the lack of familiarity, on behalf of many DAF participants, with the relational mindset and forms of leadership that are promoted in DAF:

For [people] who have worked exclusively in hierarchical organizations their whole lives, shifting into a network mindset can take some time, given how it contrasts with Western assumptions of how change happens through deliberate planning and control. … Hierarchical leadership is directive and consolidates control. Network leadership is facilitative, generating connections between others and decentralizing power such that people can organize without a top leader. (Ehrlichman, 2021, pp. 38–39)

New practices could be adopted in DAF to better support emerging initiatives and catalysing new learning – for example, setting up an innovation fund, which is a “small pool of money that provides seed funds or incentive funds to encourage self‐organization and collaboration” (Holley, 2013), or engaging in joint events and partnerships with aligned networks and organisations. Such practices would likely require more robust sources of funding than were available at the time of writing.

It should also be pointed out that several people have also encountered issues in working directly with CT members and/or DAF founder Jem Bendell, which prevented them from further engaging in the network. Therefore, individuals assuming leadership roles in DAF have occasionally played a disabling role in other stakeholders’ learning.

More fundamentally perhaps, the perception that DAF gives people “no call to action,” and that it is overly “philosophical” and “open-field,” have been recurring criticisms voiced within the network. Using Wenger’s theory outlined above, these criticisms can be interpreted as calls for more stewarding governance: indeed, for many DAF participants, the network’s mission of “enabling and embodying loving responses to collapse” required more alignment and coordination in order to bring about more practical, on-the-ground initiatives that may reduce the social, political, and ecological impacts of collapse. Perhaps these statements also expressed a desire for more attention to “collapse-readiness,” as compared to the focus on “collapse-transcendence” which has grown more central in the network since its creation, as exemplified in the attention to doing “inner work” and cultivating relational processes.

Finally, from a purely pragmatic perspective, it may be that DAF’s governance model, characterised by its focus on emergence, would prove unsustainable, due to the difficulty of securing funding for efforts involving relational (as opposed to transactional) ways of organising, whose outcomes are impossible to predict – a difficulty acknowledged by other practitioners (such as David Jay, or the Starter Culture collective).

In this regard, it may be that systems of governance that are distributed but preserve more elements of vertical accountability and concentration of decision-making power, could be more reassuring to funders.

In brief...

In this (rather bulky!) summary, we have seen that according to research participants, DAF had played an important role in helping them to live with the difficult emotions brought about by their awareness of the planetary predicament; and that a relational paradigm was cultivated in various parts of the DAF landscape of practice, allowin many participants to find deep experiences of social learning taking place. These practices displayed the potential to foster long-lasting world-view transformations towards expanded forms of social and ecological consciousness as a form of radical collective change, although more research is required to confirm this aspect.

On the organisational level, there are signs showing that an increasing number of active DAF participants were growing more proficient with the emergent governance promoted in the network, through self-organised practices scaffolded and disseminated in the network. However, self-organisation had not grown to its full potential in DAF yet. Most importantly, it appeared that the choice, on behalf of the Core Team, not to promote more directionality (or stewarding governance) in the network was experienced as disorienting by many, particularly with regards to the emphasis on inner work and relationship-building. While this governance was a reflection of the prefigurative aspect of DAF, it may be all the more troubling to those participants who are more intent on enacting practical or political changes, and regretting the absence of guidance in this regard. Similarly, this relational, inward-oriented focus made it more challenging for the network to resource itself financially.

It is time to address a thorny question: that of DAF's relevance to socio-political change! In the next summary, which will conclude this series of summaries of my research on DAF, let's look into this question using a different perspective than we have so far: a decolonial lens.